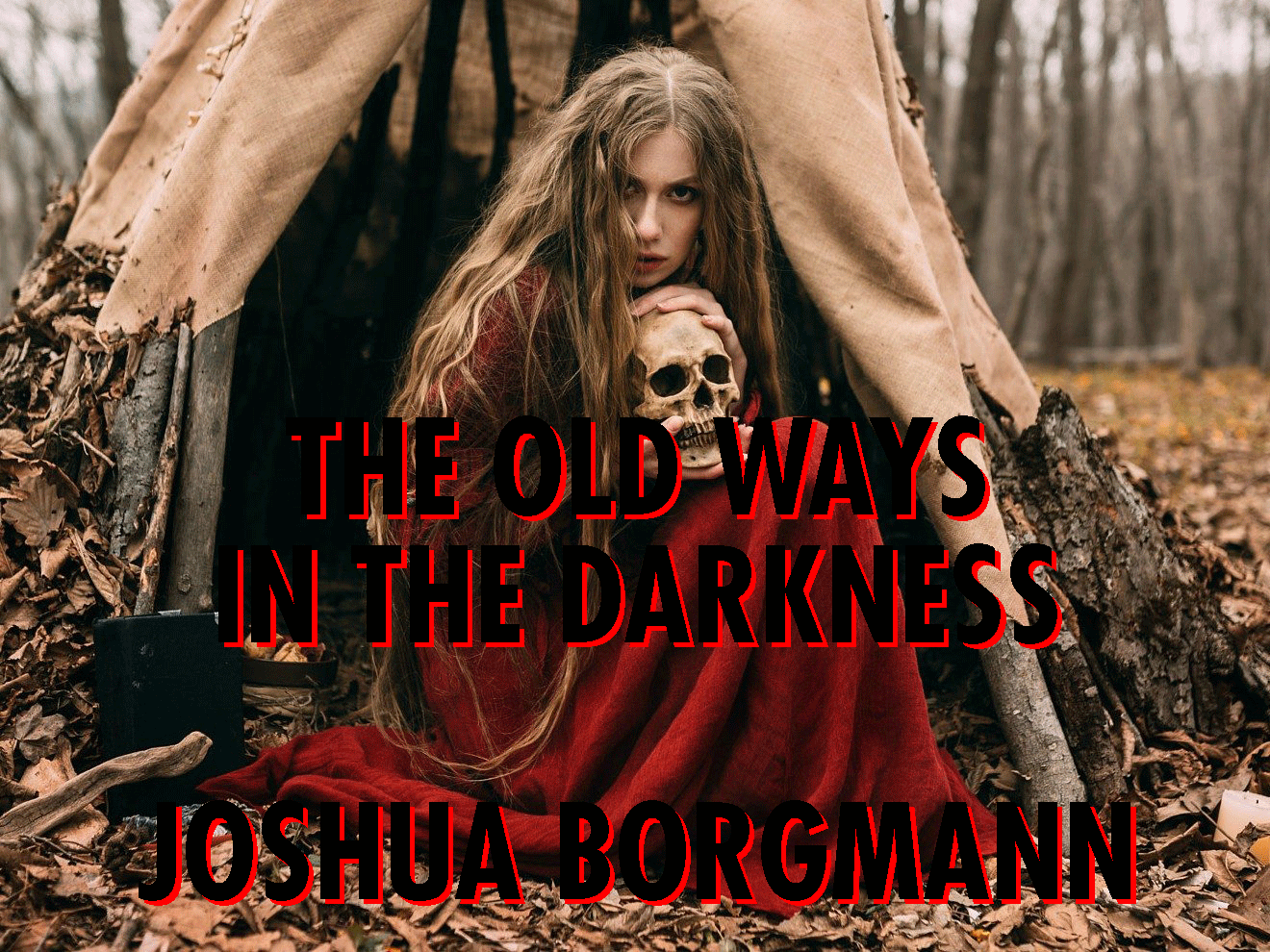

the old ways in the darkness

by joshua borgmann

[A Spotify Playlist for this Essay]

I begin this piece during the last days of October in the shadow of Halloween, our pale imitation of the great festival of Samhain. Even with the corrupting embrace of commercialism and Christianity, Halloween still holds a special place in my heart. It is the one holiday that the Christians haven’t been able to completely tame. Of course, depending on who you ask the current version is little more than an excuse for cosplay, a tribute to evil, or a windfall for candy-makers. Yet I’m sucked into the commercialism as well. I bask in the candy and the “horror” elements. One might say that modern Halloween was made for people like me who seldom leave the world of horror, science fiction, and super heroes. However, as a man of Northern European heritage who openly rejects organized religion, the shadow of Samhain and my Celtic/Anglo-Saxon ancestors is forever present. Whether I choose to take any story as fact makers little for me because I find more “truth” in the mythology of the British Isles and Scandinavia than I do in the Hebrew Bible. I’m born of the British Isles (and I like to think a little bit of Viking lurks inside me) not of the Middle East or Rome. I’d like to think my ancestors fought the Romans and their Christian religion. I’d like to think that I have witches or druids somewhere far in my ancestry. As an eternal skeptic, I can’t say that I am a true Pagan, but I will say that the blood of Pagans flows through me. This blood pulls me toward the dark, the mysterious, and the gothic.

I’d like to say I was goth when goth wasn’t cool, but the truth is that I never got to fully embrace my goth self as I was stuck in a small town in the endless cornfields of Nebraska where “goths” didn’t exist and metal fans leaned hard toward the gearhead variety rather than the black-clad princes and princesses I craved. Still, I grew up in the embrace of heavy metal, starting with AC/DC and making my way to Metallica and Slayer and eventually to Norwegian black metal and British gothic metal masters Cradle of Filth. I was also all over the gothic side of metal: Type O Negative is one of my all-time favorite bands, and Marilyn Manson is an artistic hero. I encountered real “goth” music a few times on my path, but it was always just a few songs here and there. I’ll openly admit that I heard Cradle of Filth’s cover of “No Time to Cry” before I ever heard Sisters of Mercy. However, I would occasionally come across a goth compilation disc or tape that would introduce me to bands like Bauhaus, Nosferatu, and Inkubus Sukkubus.

Metal gave me Satan, but as I came to learn, Satan was only useful within the bounds of the Christianity that I was rejecting. Satan is not a Pagan god, and “devil worship” is nothing more than a twisted version of Christianity. Truth be told, most modern “Satanic” metal bands either play Satan off as a gimmick, use the character as a symbol of opposition to Christianity, or practice the kind of Satanism put forth by The Church of Satan, which has little or nothing to do with a Satanic god. I’ve always loved the idea of Satan as a symbol of opposition, so bands like Behemoth that use Satan in this fashion appeal to me, but as I went deeper into the metal underground, I discovered bands that focused more on the mythology and literature of Northern European cultures such as the Vikings. Little gives me more pleasure than listening to Amon Amarth spin tales of great Viking battles in tracks like “The Pursuit of Vikings” and “Twilight of the Thunder Gods,” and being of Northern European descent I identify with these tales and find man-gods like Odin with his obsession for seeking knowledge more appealing than Yahweh’s Hebrew/Roman origins and all-knowing yet unknowable nature. However, these tales seem to only focus on a masculine side of Paganism, and as I learned more about modern Neo-Paganism, I knew that goddess-centered beliefs were just as important, especially in the more popular Neo-Pagan traditions like Wicca. Is there Wiccan metal? Yes, metal has covered just about everything at this point; however, I found a deeper exploration of the Pagan feminine in “goth” especially in bands like Inkubus Sukkubus and Faith and the Muse.

Heavy metal to me is a brother to goth, dark wave, and dark folk. All of these genres draw on gothic themes and imagery and there is plenty of death, sex, and vampirism in all of them. Openly challenging the Christian status quo is not uncommon. However, while heavy metal often concerns itself with battle, goth and dark wave often concern themselves more with seduction, and dark folk like Wardruna, Skald, Faun, and Heilung concern themselves more with recreating the lost. However, when I speak of seduction, I speak of more than the vampires and the sex. Seduction in explicitly Pagan goth is much more about reinventing feminine power than it is about simply being sexy. Much Neo-Pagan goth can be viewed as hymns to ancient goddesses and occasionally gods. Bands like Inkubus Sukkubus are more concerned with restoring the goddess and overturning the patriarchy than they are with sexy vampires and dark castles even if those elements appear occasionally.

Where does Neo-Paganism’s foothold in goth music begin? I’m not a goth historian, but the band that most often receives credit for inspiring other goth Pagans is Dead Can Dance. Consisting of Brendan Perry and Lisa Gerrard, the group formed in Melbourne in 1981 before transplanting themselves to London a year later. Dead Can Dance certainly embrace pagan themes in their music and more importantly set a standard of producing a very varied catalog and incorporating elements of classical, electronic, drone, and medieval music into their sound. This tendency to experiment and embrace other styles certainly has had an impact on dark wave and in particular on dark folk bands. The group’s middle period albums such as Within the Realm of a Dying Sun, Into the Labyrinth, and Spiritchaser are definitive works of Pagan goth, 2012s Anastasis is a modern statement of Pagan values, and 2018s Dionysus is essentially a Pagan ritual transformed into song.

The primary source of Dead Can Dance’s Pagan imagery tends to be Ancient Greece. The god Dionysus is mentioned over the course of several albums culminating in the 2018 album serving as a Dionysian ritual. Earlier, Within the Realm of a Dying Sun served as a kind of defining moment for the group as they shifted from a more traditional rock sound toward a sound that embraced world music, cinematic scoring, and heavy use of Gerrard’s ethereal neo-classical vocals. Ancient Greek themes played out in tracks such as “Persephone (The Gathering of Flowers)” and “Summoning of the Muse.” In many ways, this album provided the blueprint that contemporary Pagan folk bands draw from. The title for 1993s Into the Labyrinth is closely linked to the tale of the Minotaur’s labyrinth, a tale that is specifically referenced in the track “Ariadne.” In addition to the obvious Greek mythology, Into the Labyrinth also draws on the mythology and traditions of Australia in “Yulunga (Spirit Dance) and Celtic Ireland in “The Wind That Shakes the Barley” and “Tell Me About the Forest.” Spiritchaser brings India into the Dead Can Dance sphere on the track “Indus,” a track that also draws on melodies original written by George Harrison of the Beatles.

Dead Can Dance were officially broken up for most of the 2000s; however, they released a new album in 2012. Anastasis is one of their finest recordings featuring some of the clearest statements of Pagan belief and some of the most stunningly beautiful examples of Gerrard’s vocal stylings. The album once again references Ancient Greece as the title is Greek for “resurrection,” which is very fitting considering it was the group’s first recording in sixteen years. Furthermore, contemporary Paganism tends to draw heavily on nature, and while the natural world is mentioned throughout Dead Can Dance’s catalogue, “Children of the Sun” provides one of the group’s clearest statements about the divinity of the natural world. Perry sings of being “ancients” born of the sun and sea and speaks of making ancient offerings to elemental forces through ages of iron, bronze, and stone, all sacrifices that were “Made for…beauty, peace, and love.” As with many contemporary pagan songs, Perry suggests that what once was will be again and that “our songs will fill the air.” The song is an epic reintroduction to the band and makes it clear that Dead Can Dance still has plenty to offer. The group continues to prove this on 2018’s Dionysus, a relatively short album divided into two parts: a three movement “Act I” and a four movement “Act II.” The songs tend to function more as a meditation or ritual than they do as traditional rock songs although the tracks certainly utilize many tools of electronic music. Once again, Dead Can Dance seems to be evoking the ancient in a way that seems completely new.

While I heard a few Dead Can Dance songs when I was younger, the first band that truly brought me into the Neo-Pagan goth fold was Inkubus Sukkubus. I remember hearing “Belladonna and the Aconite” sometime during the 1990s. Back before ITunes, Spotify, and YouTube, it was a lot harder to find music by the band as they didn’t have a lot of success in the United States. However, I was able to track down about a dozen songs and really enjoyed them. This corresponded to my college days when I was first introduced to various forms of Neo-Paganism such as Wicca and The Church of Satan. Over the years, I remembered these songs, but at the time, I was drawn more toward the sexy vampires and dark castles of Cradle of Filth. However, as their music became more readily available, I ended up gravitating more and more toward Inkubus Sukkubus, and they’ve become one of my favorite bands.

Inkubus Sukkubus is undeniably an important band to discuss when considering goth music and Neo-Paganism both because they are so explicit in their embrace of Wiccan themes and imagery and because they have been making music for decades The band was formed in 1989 by vocalist Candia Ridley (now McKormack) and guitarist Tony McKormack with bassist Adam Henderson in Cheltenham, Gloucestershire, England, and their first independent album Beltaine was released in 1990. The group has continued to consistently release albums and tour (primarily in the UK) ever since. In 2018, the group released two albums, the goth rock album Vampire Queen and the folk Sabrina. The Neo-Paganism expressed in Inkubus Sukkubus’s songs tends to fall into two camps: those that paint Christianity as a colonizing force that does more evil than good and those that focus on the return of the sacred feminine and the power of female sexuality.

Metal and goth both embrace some of the darker icons of Christianity and folklore. The devil, the vampire, the werewolf, demonic creatures, and vengeful spirits. Inkubus Sukkubus uses many of these same icons, but the band uses them in a much different fashion than many of their metal contemporaries. Whereas metal bands often draw on the story of Satan and use the fallen angel as a symbol of opposition to Christianity, Inkubus Sukkubus challenges Christianity at its most basic level: by painting it not as a religion of love and salvation but as a tool of brutal colonization and genocide. In the world of Inkubus Sukkubus Christianity is not a choice but something that has been forced on all us and holds us captive to a hypocritical morality that says “do as we say not as we do.” The Christian missionary becomes a brutal slaver spreading lies with his guns, swords, and poisoned words. Satan is no longer a symbol of opposition to Christ for the world of Inkubus Sukkubus he is the preacher in the pulpit.

Perhaps the purest reflection of this concept of Christianity is found in 1993’s “All The Devil’s Men.” The lyrics of the song paint a story of men of “God” spreading their faith through war, torture, genocide, and forced reeducation. The Christians are the devil’s men and mankind is their victim. There can be little doubt what is meant with lyrics like,

Hear the children scream

For they shall teach them Christian values

Put monsters in their dreams

And subject them to pain and torment

With their straps and with their canes

They shall teach them fear and shame.

These lines depict the insidious manner that Christianity was spread throughout much of the world. Many want to believe that this was simply a case of people seeing that this new sky wizard offered by Christianity was better (the one true god), but the truth is that violence and war were often the prime tools, and often native Pagan populations were converted by removing children and making the stripping them of their cultural identities to remake them in a Christian image. Attempts to convert Native American children come to mind as a prime example of this; however, the same was true of many other cultures that had the misfortune of running into European Christians. While the missionaries of the day might say that this was for the good as it brought people to Christ, it is clear that Inkubus Sukkubus sees it as what truly was an attempt to for the next generation of subjugated people to become their own subjugators, for, as the song states, “if they can’t burn you at the stake, your children they will take.” However, while the lyrics suggest that there is no difference between God and Satan as both are “the twin gods” of the devil’s men, there does seem to be a line drawn between those who do the actual evangelizing and those who have been converted. This arises from the lines “What they do, they do for Christ /And we are all the victims /Every man, woman and child” and “In the shadow of their cross / Lie the victims of their tortures / In the churches and the schools /They still take us for their fools.” The song closes with a glimpse of hope by suggesting that Christianity’s hold has become a “dying empire” that shall “fade into the past.” Of course, one should remember that this song came out the year I graduated high school (almost twenty-five years ago), and no grand revolution has freed us yet.

“All The Devil’s Men” is certainly an obvious example of the song that paints Christianity as a corrupt colonizing force; however, the band has many others. “Conquistadors,” “Preacher Man,” “Burning Times,” “The Rape of Maude Bowen,” and “Church of Madness” are only a few of the songs that echo the message of “All the Devil’s Men.” However, the band does draw on the power of the fallen Pagan gods and goddesses to offer hope. Aside from the end of “All The Devil’s Men,” the best example of this is their early anthem “Beltaine,” a track named for the great festival that is echoed in our modern May Day. While “All the Devil’s Men” approached things from a historical perspective, “Beltaine” sticks to the land of mythology painting at first a dark picture of a land where the ancient gods and goddesses have been forgotten:

It has been two thousand years

The earth is soaked with blood and tears

The once-great Lord of the Hunt lies slain

His bride's a-burning in the flame

Mother Earth lies raped and poisoned.

However, this darkness is challenged in the chorus which suggests a revival of the old ways:

I hear the Pan Pipes playing

In what the wind is saying

Here comes the fallen angel

Here comes the long-dead god

Back from the years in exile

Here comes a wild Pagan hunt

In particular, the way that the word “hunt” is stretched out to the extent that it could easily be heard as “heart” adds additional gravity to this and makes clear that the old ways are rising again. Whether this is reality or just imagination makes little difference as the song serves as an inspiring rallying cry. “Beltaine” is a song that bridges the gap between Inkubus Sukkubus’s anti-Christian moments and their embrace of a deeper Wiccan view that focuses more on goddess worship and female sexuality as an alternative to Christian patriarchy. The idea of exile that is introduced in “Beltaine” carries throughout numerous other songs in which goddesses, nature, and supernatural creatures are all seen returning from a long exile. For the most part, these icons are all associated with the feminine and in particular with female power, especially sexual power.

“Heart of Lilith” is perhaps the best example of how Inkubus Sukkubus uses the image of an exiled goddess to bring back a sacred feminine that is both sexual and sublime. The song uses the character of Lilith, Adam’s exiled first wife, as its central symbol. The choice is expertly made as in some accounts Lilith was banished for being too powerful; a strong female figure wasn’t acceptable, so the powerful vision of Lilith was replaced with the much weaker Eve. Lilith as such becomes a sort of Pagan symbol for female sexual power. The song centers on the idea of Lilith’s power: She is not simply an object to be desired but desire itself. She is predator not prey. It’s not that she is evil, but rather that she is dangerous; she is sublime. As the song states,

She has come from the shadows of the dream world

A dark angel from the darker side of love

Across a sea of tears

A hundred thousand years

Come with her and dance in the moon light

And you are lost to this world evermore.

Lilith is said to be “a dark angel from the darker side of love.” She is not some weak figure that can simply be objectified and used for the desires of men. In fact, while she is beautiful, her powerful sublime nature is revealed when it is stated that dancing with her will cause one to be “lost to the world evermore.” Her beauty is not beauty that is safe to look upon as doing so is likely to destroy or forever change the viewer. The balance between her sexual power and her destructive/transformative nature can be seen in the lines, “Come and drown in the lake of her passion / Come and die so you can be reborn.” She is transformed from an object of desire to desire itself and that desire has the power to destroy and utterly change who accepts her embrace: such is the nature of the sublime, of the goddess.

At several points, Lilith is portrayed as returning from exile from “the dream world,” “across a sea of tears,” and after “a hundred thousand years.” There are also references to “rising like a phoenix.” So what is it that is rising again? What does Lilith represent? One key is noticing that she is referred to as “a witch, a siren, a vampire.” These are all words that suggest a kind of evil, but also can be used to diminish a woman of power. However, they are not used in a diminishing role here. These words are said with a kind of reverence as an embrace of her supernatural power, of her sublime nature. What does she represent? She represents the idea of feminine power that has been held down for too long. Furthermore, she represents all elements of that power including the sexual, which is too often dismissed as a tool of the patriarchy when this is not always the case. This Lilith, this sacred feminine may be desirable, but she is no mere object, and her existence challenges the very foundation of the patriarchy.

“Heart of Lilith” is just one song that embraces the power of the scared feminine and uses goddess imagery to challenge the patriarchy. Other notable songs that express similar ideas include “Wytches” with its invocations of various goddesses, “Queen of the May,” “Woman to Hare,” “Call Out My Name,” “Dark Mother,” “Midnight Queen,” and “Trinity.” Even a song like “Vampyr Erotica” that seems to embrace common gothic themes of vampirism is actually steeped in the language of female power and sexuality.

While Inkubus Sukkubus is perhaps the best representative of a clearly goth band that embraces largely Pagan themes, they are certainly not alone. Faith and the Muse also travel an openly Pagan path within the confines of goth music. However, Faith and the Muse seem more concerned with exploring the mythology of the British Isles than in preaching against Christianity. Many of the group’s songs draw on Welsh and Celtic legends for material. “Cernunnos” is one such song that echoes many of the same ideas put forth in Inkubus Sukkubus’s “Beltaine.” Cernunnos is the ancient Celtic name for “the horned god” who represented fertility, wealth, and animals. In Faith and the Muse’s song, we here this god speak of his long exile and the state of the world before and after his reign. The lyrics state:

Harmonious the centuries

The land and I were one

My soil, my water, my air

Bringer of light

And master of night

In balance, the earth in my care.

The great god describes the world under his care as a place of harmony; however, as we move through the song, he states that the winds brought change. He refers to this change as “a tide of corruption” that eventually sweeps away his reign. Cernunnos, however, isn’t ready to stand idle while the world falls into disarray. He states,

Your new gods, your new ways

All seek to dispel me

With doctrines of fear built on lies

The hidden one, no longer

I claim my dominion

To the sun of your age, I arise

After stating that he will arise, the great god announces a list of mankind/Christianity’s failings that he wishes to sweep away including anger, greed, ignorance, sorrow, and bloodshed. The god makes clear that he will have no more of this “rotting age” and will bring back the old harmony before concluding with a “blessed be.”

It is very clear that this song follows in the same footsteps as any number of Inkubus Sukkubus songs. The central idea is that the old ways will rise again and replace the destructive ways of modern man with something more in harmony with nature. In this case, the representative is a god rather than a goddess, but the central themes remain the same.

Faith and the Muse offer other songs that embrace Pagan ideas and draw heavily on Celtic traditions. In “Boudiccea,” the group uses the ancient Celtic queen who defeated the Romans in several battles before killing herself rather than being captured as a symbol of female power. The song is again told from the perspective of Boudiccea (a Latin spelling) or Boudica (a more proper Celtic spelling), but the song deals very little with her own accomplishments. She instead reflects on how “the impossibility of Womanhood vexes her.” She claims not to understand the desire for delicate wrists and gaudy make-up. In fact, she puts forth that the heart of a woman should have nothing to do with these things. The heart of a woman, in her eyes, should be a thing a power. She who stood against the might of Rome and died rather than be made a slave represents the true potential of a woman. She seems to blame the Romans and later Western Christianity for making modern women too docile when she says, “Some may dress and act the glamour'd part but they'll never have a woman's heart.” The song seems to be an invitation for woman to seize their true potential and not settle for being the objects of men’s affections. This is in line with some of the ideas of female power that Inkubus Sukkubus embodies; however, Faith and the Muse seem more concerned with the idea of political and social power rather than primarily sexual/spiritual power. Still, the call remains for woman to not allow themselves to be tools of the patriarchy.

Dead Can Dance, Inkubus Sukkubus, and Faith and the Muse have been actively recording and performing music for decades, and it is impossible to ignore the influence that each has had on newer groups. Goth itself has morphed into many different facets and left impressions on various genres. While it is undeniable that heavy metal and industrial have been greatly influenced by goth, there has also developed a sort of dark alternative folk music that bares many of the hallmarks of goth. In fact, the March Vladness committee has seen fit to include a few tracks that might better fit this genre such as Nick Cave and the Bad Seed and Sixteen Horsepower. Saying that there is a single genre that can be labeled as “dark folk” is a bit ludicrous because as with most genres, there are numerous sub-genres that each claim to represent something different. In dark folk, one might find groups that could be labeled “alternative rock” like Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, more tradition singer songwriter folk like William Elliot Whitmore, shoegaze influenced acts like Emma Ruth Rundle, acoustic black metal, and a strain of neo-folk that often relies on the use of classical and ancient instruments. Pagan themes can appear in any of these genres, and they have certainly appeared in the more traditional folk style with bands like The Moon and the Nightspirit; however, it is this strange neo-medieval branch of dark folk that best displays elements of modern Neo-Paganism. Bands like Wardruna, Faun, and Heilung have taken Dead Can Dance’s flare for using alternative instruments and alluring vocals and transformed these elements into a full-fledged attempt to recreate something ancient and at its heart very Pagan.

Wardruna is one of the most successful “world” music groups currently performing. This success is largely due to the fact that primary composer Einar Kvitrafn Selvik worked with composer Trevor Morris on soundtracks for Seasons II and III of History Channel’s hit series Vikings. Similarities exist between these soundtracks and Wardruna’s music; however, it is important to note that Morris’s goal is to incorporate Nordic elements into modern cinematic scoring while Selvik’s goal in Wardruna is to create modern music using the instruments, meters, and languages of the ancients. For Wardruna, Selvik has taken instruments such goat-hide drums, mouth harp, flutes, goat horns, tagelharpa (a kind of bowed lyre), and kraviklyr (an ancient harp that looks something like a combination between a guitar and a harp) and combined them with lyrics set to ancient rhythms and sung in either Old Norse or modern Norwegian. While the instruments and language are ancient in origin, one cannot say that the sound is particularly similar to what one would have heard in Viking times. Selvik draws heavily on contemporary influences such as Dead Can Dance style goth folk and Norwegian black metal. In fact, prior to recording the soundtracks for the History Channel, Wardruna was mostly known in black metal circles. Some might even say that the band is essentially playing black metal on ancient instruments. The result is that much like Dead Can Dance has been doing for decades, Wardruna creates music that the evokes the ancients and calls out to their Pagan roots while still being completely new and modern. Tracks like “Tyr,” “Fehu,” and “Helvegen” showcase this strange new sound.The 2018 album Skald moves into a more traditional Nordic folk direction, but this is intended to be a one off rather than a complete change of direction.

Other bands have forged similar styles with Heilung embracing the idea of folk metal as a kind of reinvention of pagan ritual, Myrkur showing that she can compose both within the framework of black metal and traditional Nordic folk, and Faun displaying how ancient instruments can be featured within a folk-metal framework. I expect that bands like these will continue to push the boundaries of Pagan music in the coming decades.

Are medieval folk bands like The Moon and the Nightspirit and folk metal bands like Wardruna goth? I don’t know. It is hard to truly define what is goth music. Certainly, most people will agree that Bauhaus, Sisters of Mercy, early Cure, and early Dead Can Dance are goth. Inkubus Sukkubus and Faith and the Muse certainly fit that mold, but others I have mentioned do not. The truth is that you could ask whether much of Dead Can Dance’s material fits the traditional goth mold. In the end, I am less concerned with the term goth than I am with showing that Dead Can Dance and Inkubus Sukkubus have helped to forge a genre of pagan music that didn’t exist before them. In fact, it is very telling that Dead Can Dance’s 2018 release has more in common with Wardruna than it does with the Cure and that Inkubus Sukkubus released two albums in 2018 one featuring traditional goth rock and the other dark folk. The Pagan god’s have not died away. They continue to grow and wait beyond the veil of the vapid mainstream. Look for them and you shall find them. And now as a new year dawns, I finish what I started in the shadow of Samhain. Beware of the things that lurk in the dark and blessed be.

I’ve created a Spotify playlist to go along with this essay. The central bands are Dead Can Dance, Inkubus Sukkubus, Faith and Muse, and Wardruna. I’ve included selections that could be labeled as goth, folk, and metal. In the end, it may lean more toward the Pagan folk side than the goth side, but it’s hard to avoid that when Dead Can Dance is one of the anchor bands.

https://open.spotify.com/user/1288522/playlist/0i1i3IGa4FHXMNLYsU1ksI?si=TlxWx3ErS_KvlWUn54NtJg

Joshua Borgmann became fascinated with all things dark, spooky, and taboo after watching family members kill and butcher a goat when he was ten. As a teenager, he played the role of that weird kid who read horror and listened to scary music. He spent much of this time reciting disturbing poetry in cornfields and locker rooms, which earned him a trip to a therapist. In his twenties, he moped around complaining about being single and unloved, but somehow earned a couple of advanced degrees. He now moves around complaining about not having enough money as he reads weird books, listens to scary music, teaches at a community college, and works as a servant to a small army of cats.