the first round

(4) terry jacks, “seasons in the sun”

UNDRESSED

(13) david lee roth, “california girls”

278-218

AND WILL PLAY ON IN THE SECOND ROUND

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on March 9

The Branching Tree of Bad Decisions: Kathleen Rooney on “seasons in the sun”

During the Renaissance there was a vogue for the “paradoxical encomium,” a rhetorical jest typified by Ersasmus’ In Praise of Folly. This form of virtuosic display originated in adoxography, an ancient Greek practice of praising people, things, and conditions undeserving of praise, such as poverty, ugliness, stupidity, drunkenness, and so forth. Often semi-satirical, the paradoxical encomium was a playful transformation of negatives into positives, flaws into strengths. In other words, the paradoxical encomium could be an early formula for admiring something so bad it’s good.

This essay, though, is not going to be one of those, because “Seasons in the Sun” by Terry Jacks flat-out sucks.

The saccharine dramatic monologue of a dying man bidding his beautiful world a tearful farewell, the ominous, aqueous, jangling riff that opens Jacks’ take sounds promising, as though it might not be out of place in a Scott Walker song. Alas, then, Jacks’ twerpy voice begins to mewl followed closely by a needling organ, and within 15 seconds, the combination makes this listener think of the terminally ill narrator: Just die already. It’s a melody you can imagine coming out of a slot machine. A carousel from Hell going endlessly up and down a little too fast, never stopping to let you off.

Somewhere between 11 million and 14 million people who have bought the single worldwide would disagree with me. Released in the United States in December of 1973, the song cracked the Billboard Hot 100 in January of 1974, ascending to the number one spot by March 2 and remaining there for three weeks, after which it stayed in the Top 40 until around Memorial Day. To put that achievement into perspective, “Seasons in the Sun” is still one of fewer than 40 singles ever to sell over 10 million copies globally.

Admittedly these are awe-inspiring—and, depending on how one feels about the song, dismaying—feats. Yet, because there’s no such thing as absolute authority over aesthetic value, nor any way to establish objectively or universally whether something is bad or not, it would be futile to try to prove that Jacks’ “Seasons in the Sun” ought to be heard by every listener as awful, or that millions of people are wrong for liking it.

It would be more fun instead to study Jacks’ version’s path into existence—to make ourselves the Lomaxes of soft rock for a sec and follow “Seasons’” lines of descent. Because whatever else it does, Jacks’ take on “Seasons” provides an invaluable object lesson in how poor decision-making can diminish a particular work’s quality in a way that’s illuminating about art in general.

Before doing that, though, I confess that it’s tempting to crap spectacularly all over Jacks’ effort. Plenty of people have. The reference series Contemporary Musicians describes Jacks’ version as a “schlock/pop classic.” Schlock, of course, means cheap or inferior goods; trash, deriving from the Yiddish for dregs, dross.

In 2018, the blog Cracked Rear Viewer, dedicated “to fresh takes on retro pop culture,” called the song a “schmaltzy little ditty” and shared it with the warning “ATTENTION DIABETICS: better take your shot of insulin before clicking on the next video!”

An August 2017 article in the Australian Inquirer entitled “The Nadir of Postwar Popular Music” reported that Jacks's version “often tops lists of the worst records of the 1970s or of all time. It was once left off such a list because it was judged to be in a category of awfulness unreachable by mere mortals.”

But the same article also reminds readers that Jacks’ offering went to Number One not only in the United States, Canada, and Britain, but also “most European countries, South Africa, New Zealand and Australia, where it stayed on the charts for 27 weeks.”

And in 2015 the Canadian tabloid The Province pointed out that, “People loved it while others loathed it, usually for the same reason: Its blatant sentimentality.”

Whenever something so polarizing achieves such enduring popular resonance one wonders: how did this happen? Was it produced to specific consumer tastes? Was it an accident? What the heck?

Maybe the key for Jacks’ hit is that he originally intended it for the Beach Boys. One imagines that if Brian Wilson had not been out of commission, then perhaps he could have given it a hallucinatory fever dream feeling more innovative than Jacks’ treacly haze.

In The History of Canadian Rock ‘N’ Roll, Bob Mersereau explains that after Jacks’ band the Poppy Family—which, as its name suggests, cranked out a considerable number of pop hits—dissolved, his interests turned toward writing and production, and he began to seek out new studio gigs. He met the Beach Boys through touring, and with Brian Wilson’s mental health crisis growing more severe, “Carl Wilson and Al Jardine both asked if I would produce them,” Jacks said. “They knew I liked the Beach Boys and Brian was out of it then.” He thought that his version of “Seasons in the Sun,” could be “the smash hit the Beach Boys were looking for to revamp their stalled career.”

Unfortunately, as Jacks recalls, “None of the Beach Boys were hanging together, you had to bring them in separately. It wasn’t unified because Brian had gone crazy. It was an honor to produce them, but […] I was just turning into a nervous wreck. I said, ‘I can’t do this anymore.’ I just left.” But he took the song with him, and his version found “markets most artists never heard of: Brazil, for instance, where it became the country’s top-seller of all time.”

In an interview preceding the Beach Boys’ rough cut of “Seasons”—

—Jacks’ wife and former band mate Susan Jacks asserts that part of the problem, too, with getting the Beach Boys to finish their recording was the divisive nature of the song. Her interlocutor says, “The interesting thing about ‘Seasons in the Sun’ is that’s one of those songs where you either love it or hate it. I have seen people vote that as their all-time-favorite song and I’ve seen other people say it’s the worst song that was ever written. I don’t know. That’s true of a lot of tearjerkers…” She agrees, “Oh, I know, I know, and they’re usually hits,” before sharing her version of the experience during which the Beach Boys, “went into the studio and they could never get it finished because some of the guys were really into it and some weren’t.”

So is the subsequent solo Terry Jacks version of “Seasons in the Sun” the worst song of all time? No, “My Ding-A-Ling” by Chuck Berry (repped in this tournament by the inimitable Martin Seay) is. However, part of being bad has to do with missed opportunities and dubious choices, and by that metric, Jacks’ “Seasons” is a serious contender.

How did this song get into Jacks’ hands to try to hand it to the Beach Boys in the first place, and why does his version sound so sugary when compared to its spicier source material? Let’s climb the branching tree of bad decisions and find out.

I. Brel, or, Avant Jacks, Jacques

The mawkish melt of gooey cheese that is “Seasons in the Sun” is an adaptation—or a degradation—of the Jacques Brel song “Le Moribond” with lyrics interpreted by Rod McKuen (about whom more later).

The Brel original absolutely slaps:

Compelling in its lyrics, its arrangement, and its delivery by its composer, one can see why Brel was basically the Belgian Elvis. Little wonder that musicians from the aforementioned Scott Walker to David Bowie to Joan Baez to Marc Almond to Cyndi Lauper and on and on have covered his songs.

Sarcastic and bitter, Brel’s first-person narrator is also dying and making his farewells. He says goodbye not to Jacks’ “trusted friend,” but to a specific “Emile”—“as good as white bread”—whom he knows “will take care of my wife,” a lyric whose meaning becomes more unsettling the more Brel repeats it.

The chorus, too, has a frantic quality that seems sort of shocking the first time we hear it:

I want everyone to laugh,

I want everyone to dance,

I want everyone to have fun like crazy people

when they put me in the hole.

He bids adieu, too, to the curé, or parish priest, with whom he admits that he didn’t always agree, but with whom he feels kinship because “we were seeking the same port.” He knows, again, that because the priest was her confessor, he “will take care of my wife.”

The source of the song’s intriguing unease exposes itself fully at last when the narrator makes his goodbye to an Antoine. “It’s killing me to die today while you are so alive / and even more solid than boredom” he sings in a truly sick burn. “Seeing that you were her lover,” he adds, “I know that you will take care of my wife.” The turn here reveals that this has been the nasty and impotent lament of a cuckolded husband the entire time.

At last, he says goodbye to his faithless spouse: “I go to the flowers with my eyes closed, my wife. / Seeing as I’ve closed them often, / I know you will take care of my soul.”

With its blend of macabre content and an upbeat tempo, the song is funny. We are all fools, the chorus says, and the only remedies to our folly are laughter and death.

When Brel sings, the listener senses the complete sweep of the fictional world this narrative unfolds in—Brel knows more about the milieu and its characters than the surface can show. This implication of underlying fullness enacts a musical illustration of Hemingway’s proverbial tip of the iceberg. Jacks, as will be explored below, guts the song and leaves only the tip, a lonely floe with nothing beneath.

This lack of subtext is part of why getting the Jacks after you’ve been fond of the Brel is like ordering Aperol and receiving Fanta. It’s drinkable; it’s not Drano. But it disappoints with its insipidity. Like hearing a Beethoven sonata performed by a wind-up toy, you can tell that you’re hearing a product of genius, but the mechanism delivering the song falls short of the challenge.

This listener finds Jacks’ version to be quite bad, but kind of fascinatingly extra-bad because Brel’s original is so powerful, but gets garbled almost to death in a transatlantic, international game of Telephone.

According to the best comment presently on this performance’s Youtube page posted 3 years ago by kabiriazampano3: “Jacques Brel's version is about friends and priests that he knew were doing his wife, he accepted that and recommended all of them to take care of her after his death. Terry Jacks was a version that had nothing to do with the original, american chinnese food, american pizza, american capuccino. Brel was a sarcastic poet, he went for the blood.”

II. McKuen, or, Don’t Spare the Rod

Wait, though—Jacks is not American, but Canadian. So who is the American to blame for the inferior version? Rod McKuen. Kind of.

The young and largely self-taught Bay Area singer-songwriter and poet moved to France in the early 1960s where he and Brel became fast friends. An enormous fan of Brel’s versatile and theatrical oeuvre in the genre of chanson, McKuen took it upon himself to introduce Brel’s catalog to an Anglophone audience. His version of Brel’s exemplary “Ne Me Quitte Pas”—Americanized though it is—turned that song into an international standard.

His version of “Le Moribond,” while arguably not as great as the original, is still pretty good. Significantly, McKuen altered the title from “The Dying Man” to “Seasons in the Sun,” not, obviously, because he didn’t know what he was doing, but because he did. A mindless, word-for-word translation of Brel’s lyrics would not sit well on the melody, nor would it retain the lyrical rhymes. McKuen knew that better than a translation would be an adaptation.

Looking closely at the aspects he adapts, one sees McKuen proceeding thoughtfully. One might disagree with his decisions, but would be hard-pressed to say that anything he does is mistaken or stupid:

He does lose the priest, changing him to an actual father: “Good-bye, Papa, please pray for me. / I was the black sheep of the family.”

But crucially, he keeps—and even improves upon—the cheating spouse, exhibiting that he understands the Brel song tonally; he gets the sarcasm. If anything, McKuen’s version is less sexist because he chooses to give the wife a name, while retaining the irony. “Adieu, Françoise, my trusted wife / without you I’d have had a lonely life. / You cheated lots of times, but then / I forgave you in the end, / though your lover was my friend.”

It’s not that McKuen didn’t properly appreciate Brel’s sensibility. In a characteristic and touching McKuen-esque excess of sentiment, he said that when he heard that Brel had died at the relatively young age of 49 in 1978, “I stayed locked in my bedroom and drank for a week. That kind of self-pity was something he wouldn’t have approved of, but all I could do was replay our songs (our children) and ruminate over our unfinished life together.”

Because of his friendship with the man himself, McKuen understood that he could not do Brel as Brel. He’s not a sardonic, smoldering, jolie laide Gallic icon, but an affable, sensitive, pansexual proto-hippie. Thus, McKuen’s version—not a translation, but an interpretation—makes decisions that one might disagree with, but that are ultimately defensible. He’s doing a take, not a cover, and he wants to head in a different direction.

The Brel version, though brilliant, is a bit of a mess—as can be the case with the literate genre of chanson, its lyrics are phenomenal, but the chorus hook is not that infectious of an earworm. The experience of listening feels disturbing—you get to the end and need to review what you just heard. As a composition, it’s formally complete, but keeps pulling the listener back into the knowledge that the fucked-up situation the narrator leaves behind will continue after he’s gone.

McKuen chooses to make the song smoother and more tied-up-with-a-bow, adding a much prettier chorus, both lyrically and melodically, plugging in lyrics with a variation of vowels and consonants that render it more euphonious and hookier. When you’re done with McKuen’s version, you’re still slightly unsettled, but you’re also reassured. Instead of manically telling his survivors to laugh and dance like a bunch of crazies when they stick him in the grave, McKuen’s narrator possesses memories of “joy” and “fun” and “seasons in the sun.” A bit sanitized, yes, but “the hills that we climbed / were just seasons out of time” is smartly sad, a death-tinged admission that even sunshine goes dark and rarely comprises the bulk of a life.

McKuen’s version is not bad, just different—if anything, it reveals how flexible Brel’s song is. It shows the same dramatic situation, but through a different lens. It’s not a shot for shot remake, some CGI Lion King, but rather an homage. McKuen wants a side effect of his song to be to make the listener look back to the Brel, and if they like the original better, that’s fine by him; it’s part of his aim.

Brel’s version is splenetic—contemptuous and comic and in no way wistful. But you can tell that because McKuen, too, plays the scenario as kind of a what-can-you-do joke, he at least gets the humor, even though he principally wants it to be a pretty song. Brel seems to be saying “I win because I’m dead”—a nihilistic, punk avant la lettre double bird extravagantly flipped. Even when he’s saying some of the same stuff as McKuen retains, he says it with a shrug, a hairflip, a big old IDGAF to life and everyone who has to remain in it. Is his song spoken from the perspective of a suicide? A person dying of natural causes? Either way, the parting shot seems to be, I’m glad I’m leaving and you’re staying here because you all deserve each other. Whereas McKuen’s version seems to conclude, Now that I’m facing death, I appreciate the time we had and I forgive you all. Mostly.

That mostly is vital to McKuen’s version’s emotional complexity, best embodied by the narrator addressing his wife:

Adieu, Françoise, it’s hard to die

when all the birds are singing in the sky.

When spring is so much in the air,

with your lovers everywhere

just be careful I’ll be there.

Hold on, how? As a watchful spirit full of forgiving tristesse at the absurdity? Or as a vengeful ghost seeking to wreak punishment? This edgy ambiguity, along with his various other interpretive choices, cause this listener to maintain that McKuen’s version is still pretty interesting. You can’t deny that McKuen was onto something—Brel’s song is a banger and deserved to be brought over to the States.

But his decision to excise the bitter tone of Brel’s original does open the door to some weak mis-readings.

III. Terry, or, All Jacksed Up

Enter Terry Jacks by way of that door.

At times the line between genius and foolishness seems to be a fine one. McKuen may tip this piece of Brel-ian brilliance toward foolery, but remains upright, whereas Jacks comes along and pushes it right over the edge. As biographer Alan Clayson explains in Jacques Brel: La Vie Bohème, McKuen’s version is “anodyne,” but Jacks’ version is unforgivably “harmless.” “With all further what’s-the-use-of-it-all ugliness removed,” he writes, it emerges “as a sentimental lay about some old idiot’s happy memories—with ascending key changes to pep it up.”

To listen to the Jacks version is to hear him chew a substantive song into pallid bubblegum:

In the hands of Jacks, “Seasons in the Sun” has an almost polka rhythm ill-suited to the putatively sad content. Whereas the bouncy, hysterical pseudo-cheer of Brel’s version creates a pleasing yet disturbing tension of opposites, Jacks’ version grates. He permits no comedy, no bitterness, no irony, no resentment. Puritanically, there’s no cheating wife and therefore no sex. Aesthetically unforgivably, there’s no emotional complexity.

Jacks takes something that was pretty good—the McKuen version—which itself drew on something great—the Brel—and ends up with something awful. He faced two moves at his branch of this decision tree: 1) He could have climbed back in the direction of Brel, making it more complex, or 2) He could have done what he did, clambering in the opposite direction: rendering the heretofore individual speaker into a cardboard cutout.

Jacks’ loses Emile in favor of the “trusted friend.” In McKuen’s telling, the labeling of Emile as “trusted” is caustic because we still learn that Emile has been cheating with the speaker’s wife. But Jacks allows no layers; everything is exactly as it purports to be, and the friend is truly trusted. This makes his version feel brainstemmy, stupid, repugnant—one worries, if one likes it, that perhaps one likes it for fairly dumb reasons.

But, you might be saying, isn’t Jacks doing what you said McKuen did—really, what any interpreter does? Emphasizing some aspects over others? Yes, but interpretations, like originals, can still be questionable. Jacks chooses to cut or conceal the most provocative aspects of the song, which make his version a frustrating experience, even if one is unfamiliar with its source.

McKuen drifts toward the sentimental, but Jacks crashes full-steam upon the shores of kitsch. In addition to his emblandening subtractions, the one addition he does make suggests that he doesn’t trust the listener to find the deathbed scenario sad enough. No, he opts to throw in a soon-to-be-partially-orphaned daughter (with an awkward repetition of “sun” and a cliché to end the verse to boot):

Goodbye Michelle my little one.

You gave me love and helped me find the sun,

and every time that I was down,

you would always come around,

and get my feet back on the ground.

For though aware of the Brel original, Jacks chooses to manipulate the song away from idiosyncrasy and complexity toward an empty and pandering Hallmark generality. According to a 2004 article in the Vancouver Sun, Jacks knew of the song’s unsentimental origins. “Brel wrote it in a whorehouse in Tangiers,” he said. But Jacks purposely sentimentalized it in response to “a good friend of mine” who died of “acute leukemia.” Or as the Australian Inquirer put it, “Jacks returned to the song, wrangled a few more maudlin thoughts into the last verse and recorded the syrupy results.”

Worth noting is that maybe Jacks knew exactly what he was doing from a commercial standpoint. There’s always good money to be made in pandering—producing stuff that’s ostensibly art, but that soothes and reinforces the most conservative values. Jacks’ song does not confront death, not truly. His speaker has no regrets aside maybe from regretting dying, and what interesting person hasn’t got some regrets? To the extent it has anything to say, Jacks’ version says of its narrator and by extension its listener: if you think death is sad, you are having the right feelings; the decisions you made in your life were good ones, and the values you held are the best values. Cultural products that speak in such platitudes tend to fly off the shelves.

In this regard, “Seasons in the Sun” reminds me of the colossally popular Victorian sculpture “Motherless,” which I happened to see last summer in the Kelvingrove Art Gallery in Glasgow.

Formally known as “Statue of a Motherless Girl and Her Father,” the late Victorian work by George Anderson Lawson has been phenomenally well-liked since its creation.

“It’s proof that sadness can be popular,” says the wall text explaining the piece and instructing viewers where they can purchase their copy—either in the gift shop, or online. “Also available in bronze!”

But it does not prove that sadness can be popular; it proves that sentimentality and kitsch can be popular. “Motherless,” like Jacks’ “Seasons in the Sun” gives the audience not messy, multifaceted, subtle emotion but the pure spectacle thereof; it’s not sadness, it’s SadnessTM depicted and sold, yet felt not at all.

Kitsch, of course, is something of tawdry design or content created to appeal to popular or undiscriminating taste. And sentimentality is “a device used to induce a tender emotional response disproportionate to the situation at hand, and thus to substitute heightened and generally uncritical feeling for ethical and intellectual judgments.” In this way, then, both “Motherless” and “Seasons in the Sun” induce their audiences to invest previously prepared emotions disproportionately to generic situations. Upon closer examination, Jacks’ supposed sadness does not deserve the designation of sad. It’s a simulation of sadness. A representation of sadness that’s really a simulacrum that allows its susceptible listeners to believe falsely that they’ve dealt with a difficult emotion.

In the Reading and Writing Poetry class I teach at DePaul University in Chicago, we use the text Western Wind: An Introduction to Poetry by David Mason and Frederick Nims. An eccentric and engaging book full of unexpected charts, photographs, and diagrams, the chapter called “The Color of Thought: Emotions in Poetry” includes this image of the Emotional Color Wheel.

“We can visualize the emotions as a color wheel like the ones we see in art-supply shops, a wheel in which selected colors are arranged, like spokes, according to their prismatic, or ‘spectral,’ order,” write Mason and Nims. “If we start blending the colors themselves, there is no end to the number we can make, just as there is no end to the number or complexity of our emotions.”

My students tend to find this visual metaphor particularly illuminating when it comes to improving their understanding of how a good poem operates. The idea of the Emotional Color Wheel becomes a shared term of class vocabulary—why, we ask, limit yourself to just one emotional color when you could potentially achieve a deeper effect through the use of two or many more? Or as Mason and Nims put the same concept in musical terms: “In most poems we get not one emotion in a solo, but rather duets or quartets or even symphonies of many emotions.”

We can apply the Emotional Color Wheel here. Brel’s “Le Moribond” is a rancorous rainbow of negative emotions cut through with bleak comedy. And McKuen’s “Seasons,” though less of a rainbow, still retains a pleasing balance of complementary emotional colors. But Jacks’ version displays a single, soppy color—self-pitying and weepy, smugly drunk on its own tears. Climbing the decision tree from Brel to McKuen to Jacks, the listener experiences a reduction in emotional interest—a leaching of emotional color from the song.

If you’re not yet convinced, I present two parting points as to why Jacks’ version of “Seasons” is pretty damn bad. First, it’s a full 30 seconds longer than the all-killer-no-filler 2 minutes and 56 seconds of the Brel original. Not only is it much worse, but there’s also more of it.

Second, lest anyone remain in doubt as to Jacks’ thoroughgoing immaturity and fatuous taste, the Inquirer reports this illuminating side-note: “Unlikely as it sounds, [“Seasons in the Sun’s”] B side is worse. Jacks reckoned he set out to record something unremarkable so as not to distract disc jockeys from what he saw as the main attraction. Loaded with puerile sexual innuendo, ‘Put the Bone In’ is ostensibly about a woman ordering dog food from her butcher. ‘I figured nobody's going to play that thing,’ Jacks said later.” If you hate yourself, you can listen to it here.

In the introduction to Permanent Red, John Berger writes:

After we have responded to a work of art, we leave it, carrying away in our consciousness something which we didn’t have before. This something amounts to more than our memory of the incident represented, and also more than our memory of the shapes and colors and spaces which the artist has used and arranged. What we take away with us—on the most profound level—is the memory of the artist’s way of looking at the world.

The branching tree of bad decisions shows that Brel’s way of looking at the world is incredibly colorful and interesting. McKuen’s is still interesting albeit slightly less so. Jacks’ way is vacant and ridiculous. And yet, and yet…

Without Jacks’ having sent his “Seasons” to such stratospheric fame, I doubt I’d be writing appreciatively about Brel’s original. I might not be aware of it at all. Nor would we have the many post-Jacks covers of “Seasons” that prove that—with the Jacks factor removed—the song still has a certain something.

Take Bobby Wright’s version, which hit the Billboard Hot Country singles chart in 1974, as well:

Perhaps because the expectation of corn is priced into country, this version is, to this listener’s ear, better. The steel guitar and strings, the slower chorus, and the slight churchiness make me wish dearly there were an Elvis cover.

And the Hong Kong pop band the Wynners’ version, also from 1974, sounds somehow superior to Jacks, with its slower tempo and more mellifluous, less whiny vocal.

On the other hand, there’s the 1999 version by Irish boy band Westlife, a Christmas #1 in the UK that year. With its synthesized flute and extreme chime curtain, it may, in fact, be worse than Jacks’:

Then again, there’s the Daniel Johnston version (unfortunately not readily available on Youtube), which doubles-down on the addition of Michelle, the little one, by having a child sing the chorus. The amateurish, out-of-phase quality feels worthy of a paradoxical encomium, so delightfully cracked it’s charming. Moreover, Johnston’s take possesses a beyond-the-pearly-gates cherubic vibe, like the narrator might already be dead—spooky and great.

So thanks, Jacques; thanks, Rod; and thanks, grudgingly, Terry, I guess, for all these sunny seasons.

Kathleen Rooney is a founding editor of Rose Metal Press, a nonprofit publisher of literary work in hybrid genres, as well as a founding member of Poems While You Wait, a team of poets and their typewriters who compose commissioned poetry on demand. She teaches in the English Department at DePaul University, and her most recent books include the national best-seller, Lillian Boxfish Takes a Walk (St. Martin’s Press, 2017) and The Listening Room: A Novel of Georgette and Loulou Magritte (Spork Press, 2018). Her World War I novel Cher Ami and Major Whittlesey is forthcoming from Penguin in August 2020, and her criticism appears in The New York Times Magazine, The Poetry Foundation website, The Chicago Tribune, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and elsewhere. She lives in Chicago with her spouse, the writer Martin Seay. Follow her at @KathleenMrooney

elana levin’s Notes On camp: on David Lee Roth’s “California Girls”

Camp turns trash into treasure. More than that, camp is pleased that its sources are trash but is also invested in revealing that those sources were treasure all along. This is perhaps the most forceful way in which camp distinguishes itself from similar forms of literary irony such as satire and parody. —Sarah Rasher, Dirty Old Mentors. Unpublished dissertation, University of Connecticut 2013

Music critics hate me and love Elvis Costello because music critics look like Elvis Costello. —David Lee Roth

Taking David Lee Roth’s music seriously the way you would take Elvis Costello’s music seriously is not the point of David Lee Roth. Regarding him on a good (i.e. serious, authentic) vs. bad (i.e. tasteless, superficial) axis is misunderstanding his work entirely. But talking Goodness or Badness Ain’t Talkin’ Bout Love...and I fucking love David Lee Roth. I’m going to tell you why.

LIke any self respecting rock snob mainlining underground music, I used to hate David Lee Roth. Most of my published music writing is about goth rock—real goth rock. So how did I fall in love with a song by an arena rock band that ends up in a March Badness bracket? How am I supporting a sparkly, synthy, and seemingly unnecessary 1980s cover of a song by legitimate geniuses (and eventual critical darlings) The Beach Boys?

The first time in my adult life that I even considered DLR was while watching VH1 Metal Mania late at night. My husband, a fan of extreme metal, was pretty neutral on it, but from my first viewing of Dave’s Yankee Rose video, I was reeled in by how over the top it all was.

It features:

Street-harassing the Statue of Liberty

A lycra unitard/thong combo that my dance instructor in the 80s would’ve killed for

Dave’s bare ass surprisingly close to the camera with a horse’s tail mounted betwixt

More “this guitar is my dick” preening than literally any other music video (is that what they taught you at Berklee College of Music, Steven Vai?!)

Dave’s roundhouse kick that bursts open a giant balloon containing...more balloons!

A really rocking song

This is camp. I love camp! Especially camp that subverts masculinity by revealing its artifice.

Camp taste is, above all, a mode of enjoyment, of appreciation—not judgment. Camp is generous. It wants to enjoy. It only seems like malice, cynicism. (Or, if it is cynicism, it's not a ruthless but a sweet cynicism) —Susan Sontag, Notes on Camp.

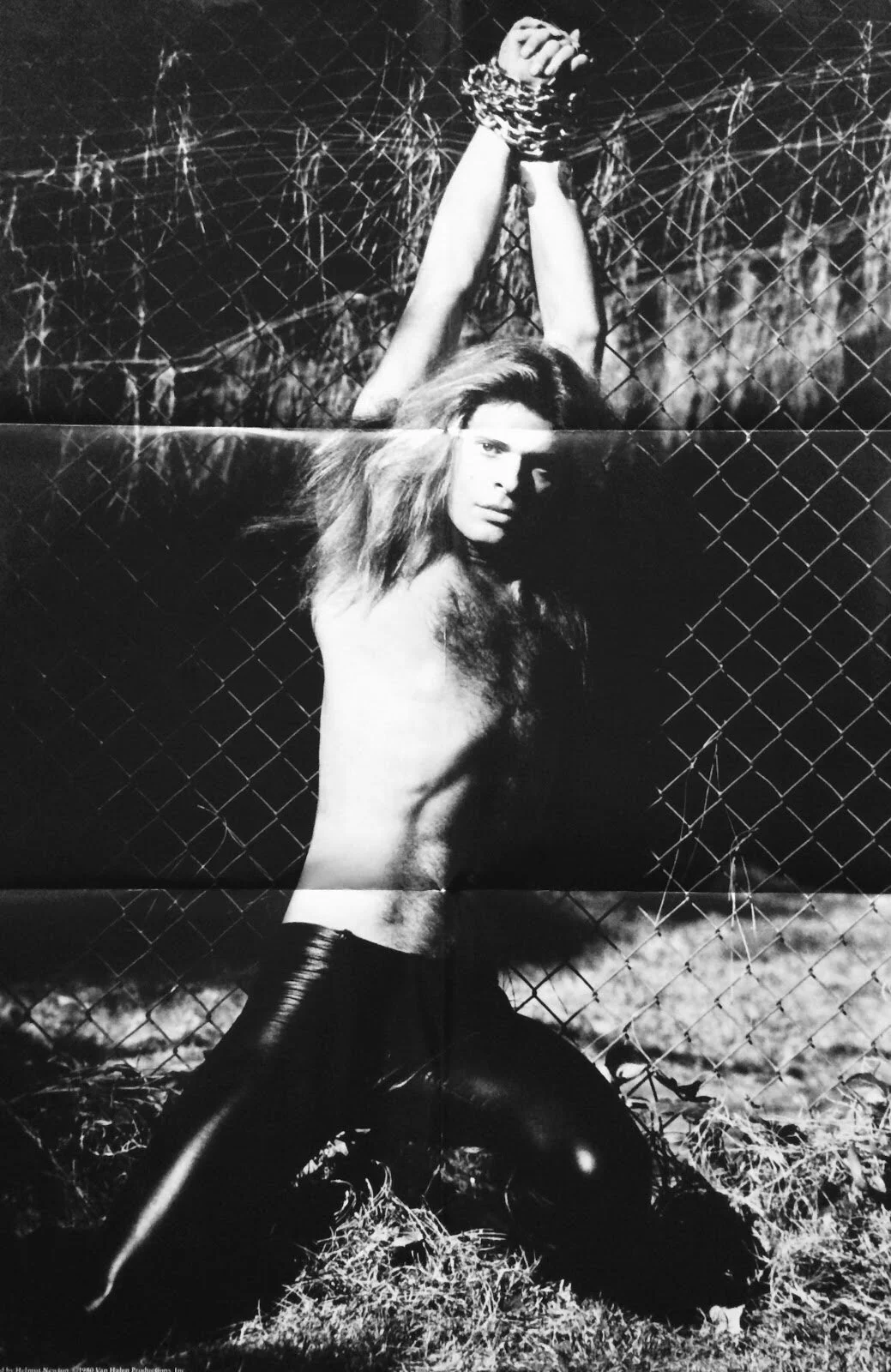

When people say that “California Girls” is bad they are missing the camp, and so much hard rock of the era is campy as hell. Camp can be deliberate or accidental. But Roth knew what he was doing when he hired legendary fashion photographer Helmut Newton, fresh off a shoot for Playboy, to shoot photos of himself bare chested in chains for the cover of Van Halen’s Women and Children First. Helmut Newton told him “You are my new favorite blond.” The band relegated Dave’s fetish glamour shoot to a foldout poster, instead of the cover. But in solo album land there is no one to tell Roth to tone anything down. Ever.

My fandom began with a certain amount of humor and detachment. “Look at this rock and roll clown’s over the top performance”. The Broadway inspired dance moves. The lycra and makeup and teased hair which—speaking as a fellow Jew—may simply be his natural hair texture plus a bit of spray. His Diamond Dave persona is a deliberate construction that he refers to in the third person. It’s a persona that he developed as a High School theater kid (of course he was a theater kid). (This is from Greg Renhoff’s Van Halen Rising: honestly, just assume any fact in here you don’t already know is from his book.)

My bar mitzvah was my first starring role —David Lee Roth

Roth’s pre-Van Halen band was performing at other teens’ Bar Mitzvahs and Quinceañeras all over Los Angeles and their goal was to make everyone dance. His band played funk music and had choreography, performing for racially diverse audiences. He was part of an integration bussing program and he loved being one of the only white kids in school.

That was the energy he brought to Van Halen. Before he joined, the Brothers Halen were doing Sabbath covers. Sabbath are gods-- but they don’t make dance music. That alone wasn’t going to make Van Halen into the massive party band that saved heavy metal. And that’s what Van Halen became, as outlined in the excellent book by historian Greg Renoff, Van Halen Rising: How a Southern California backyard party band saved heavy metal.

Van Halen is a combination of the Van Halen brothers’ heavy metal power and technical innovation mixed with Dave’s showmanship, his theater kid campiness wrapped in a legibly over-the-top masculinity. Without Dave, Van Halen’s music got dull and self serious. Without the Van Halen brothers Dave’s music was less influential but 300% campier and still incredibly fun.

Renoff tells me “from Jump to Hot For Teacher through Just a Gigolo [Dave’s solo work] you can see that kind of evolution to a more campy, ironic type of approach to performance and musical presentation which was at odds with the type of stuff (some 0f) his peers were doing in 1985. What I mean by that is that Roth's videos are much more like Cyndi Lauper's videos than like Motley Crue's videos in 1984.”

Am I going to be an original or an archetype? I’m both —David Lee Roth

But who needs a cover of the perfect Beach Boys song California Girls? This cover is excess itself! Yet The Beach Boys themselves cosigned Dave’s endeavour: Carl Wilson sings backing vocals on the track, and Brian Wilson speaks highly of it.

Are you going to tell Brian Wilson he’s wrong about this cover being good? Do YOU know better than Brian Wilson?

The Beach Boys’ Brian Wilson is one of the greatest composers ever. The instrumental intro to The Beach Boys’ “California Girls” is one of the most stunning 25 seconds of music ever made. Did you know it was based on Bach’s Jesu, Joy of Man's Desiring? More like “California Girl, Joy of Man’s Desiring.” Here, The Beach Boys’ lush 12 string guitar and horns is translated into a light tinkling synth of a melody performed by Brian Mann. California had changed a lot since the song’s 1965 heyday, and Dave is going to make it as much of a time capsule as possible.

Some have told me the video is painful to watch. I’m largely desensitized to sexist art from the 80s if it leans so heavily into camp as this does. But there are racist caricatures in the video. The ways that it is racist are really obvious and I don’t have much insight to add to it. So I’m not going to tell you HAVE to watch this video. Maybe the real badness is me, since I’ll still watch stuff like this despite the racism. But these are the other things I see in this video, if you’re willing to follow me in.

The “California Girls” video was huge on MTV: it had initially been envisioned as part of a TV movie but lost financing. There’s a Maurice Chevalier quote then it opens with a Twilight Zone voiceover welcoming us to ́the sunlight zone”. We get a fisheye lens view from inside a tour bus of a bunch of jittery caricatures of tourists visiting LA. Many of them are fucked up and I’m not going to defend them.

Under Pete Angelus’s direction, we get Dave in a white gloved bus driver uniform with a Your Guide cap making eyes at us. We’re about to get the Dave’s Eye View of California. Dave teaches you how to Dave. He is Your Guide. He shows you how to watch his video: it’s not just the Male Gaze, it’s the Dave Gaze. (Cultural critic and writer Kevin Maher coined the phrase when I was telling him about this essay.)

The video is full of Dave looking at things and directing his tour group, and you the viewer, to look at those things with him. He points at them, and the camera follows his eye lines to gaze at things. Largely he’s directing you to look at bikini girls.

But as Dave says on his YouTube series “I agree with the younger generation: a bikini is a script, a bikini is a storyline.” So we get the bikini stories of the women in their regional bikini costumes. Special shout-outs to his “midwest farmer’s daughters” tableau and his disturbingly, deeply distressed jeans in the Southern scene---also possibly his dick? Probably the only thing that can compete for attention from his ironic use of the Traitors Rag (for fucks sake don’t use that, even ironically). He also directs us to look at female bodybuilding legend, Kay Baxter, who was Dave’s trainer.

Everything in the video is as much a caricature as the national bikini girl tour get-ups. It’s a missed opportunity that the East Coast Girl who’s hip is holding a hotdog and not a bagel.

The whole video is a shtick-laden show performed on a beach. There’s also a literal garbage fire on the sidewalk. There’s some Busby Berkeley style leg dances, Fosse-esque hand and hip isolations. The end is a now famous shot of women posing as mannequins along a walkway as Dave dances between them in a bow-tie, vest and gloves, doing his iconic yelps, kicks and spins and just mugging the whole way.

There’s no David Lee Roth without the Scarecrow in The Wizard of Oz and The Nicholas Brothers. —David Lee Roth, on Design Matters podcast.

Dancing is really important to Roth’s performances. Not sure how many hard rockers talk about the choreography that inspires them. His style is a combination of martial arts-- which he studied all his life--and old school showbiz moves. He tapdances “wings” and even does Scarecrow's heel click at the end. But the fact that he’s citing the iconically campy The Wizard of Oz as well as early 20th century black tap dancers/choreographers is a pretty good thesis statement on Dave as a student of pop culture.

Only a fool thinks that just experience can replace an education. —David Lee Roth on vocal lessons on Design Matters.

One of the things that moved my interest in Roth from ironic detachment to genuine love was realizing how fun his songs are to sing. It’s not just the over-the-top lyrics, it’s his vocal lines that give a singer a lot to do in between the trademarked yelps. Dave’s voice is satisfyingly raspy while being strongly melodic and he uses it. He’s one of those singers whose speaking voice sounds exactly like his singing voice. He is actually a trained singer—which may explain how he was able to perform effectively for so long.

He got his start singing from his Bar Mitzvah coach (of course he did) who was a Holocaust survivor, and who told him “Mr. Roth, if you can't find it within yourself to sing on behalf of those who went up the chimneys with a song in their hearts, sing so you don't go up the chimneys.” (Marc Maron podcast interview) Performing is self expression, but perfectionism is a survival mechanism.

Dave often says “you don’t need to speak English to understand what I’m singing about” but for anyone who doesn’t, he did record an entire version of his Eat 'Em and Smile album in Spanish. His attempt at universalism is undermined by this video, which I understand is hard to watch for many people. But Dave wants to be understood, he wants you to join his party bus.

Unlike his subsequent solo albums there’s no killer guitar solo on California Girls. This cover is too faithful for that. It basically BeDazzlers the original song in 80’s production values and lets his campiness and the brilliance of the original composition carry the day. I think it succeeds. It’s a tribute to the aesthetics that shaped him as a performer.

Roth has said many variations of, “Music critics like Elvis Costello because music critics look like Elvis Costello.” There is truth to that. He’s not the relatable nerd. He makes music for the masses and his entire persona is about being a star. But he’s not just talking about himself when he points out critical biases, he’s talking about the MTV of his day that wouldn’t play black artists. He claims he was fired by CBS Radio for playing what the station called “too much ethnic music” when he took over for Howard Stern’s radio show. He talks enough about funk and blues artists that I believe him.

To be clear, I’m not saying he’s “woke”—that’s ahistorical and wrong. At minimum, he was active in Republican Hollywood at some point. He has racist caricatures in his videos. Those sorts of characters also exist in the vaudeville that he draws upon too. Camp can be racist.

Speaking of problematic, it’s telling that while some of the bands that followed in Roth’s footsteps (like Mötley Crüe, who I adore) have been rehabilitated in critical assessment—Roth has not. I think it’s the camp factor. He’s not trying to be tough, or serious. He is trying to seduce YOU (everyone?) and he is going for a laugh. That can be uncomfortable for straight male audiences and straight people generally don’t recognize camp. The queer audiences who might see Diamond Dave and truly Get It are largely not going to see it in the first place because it’s not marketed towards us. Or maybe they’re understandably put off by the racist video—I can’t blame anyone for that.

But you do not get those later bands without Van Halen, and you don’t get Van Halen without Roth. “I was sexually inappropriate with an entire generation, musically speaking,” Roth proclaims. He feels even more inappropriate today. That’s rock. That’s camp. That’s David Lee Roth’s cover of California Girls, submitted for your approval, March Badness 2020.

Elana Levin podcasts at the intersection of comics, geek culture and politics as Graphic Policy Radio. Elana has written about comics and politics for sites including The Daily Beast, WIred Magazine, Graphic Policy and Comics Beat and would love to have the opportunity to write about music more often. Elana is on twitter a little too much @Elana_Brooklyn and teaches digital strategy for progressive campaigns and nonprofits.