first round

(9) terri gibbs, “somebody’s knockin’”

knocked out

(8) band aid, “do they know it’s christmas”

251-210

and will play in the second round

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/2/23.

Do They Know It’s Maggie Thatcher? andrew bethke on “do they know it’s christmas”

Dedicated, with no shortage of ego or awareness of the irony of it all, to Mike Davis.

There’s consistently something…off about many of the contemporary Christmas songs that, for better or worse, fill the charts during an increasingly long period of the end of each year. From the meta-irony of Irving Berlin’s paean to Christian settler-colonialism in “White Christmas” to the violent petty larceny of The Kinks’s “Father Christmas” to Mariah Carey’s now completely ubiquitous casting of Christmas as the premier holiday for monogamous sexy times, pop music has done the seemingly impossible and turned Christmas, of all things, into a weird undefined floating signifier of whatever you might want. Christmas as pure libido, in the broadest definition. Even among this company and others (Christmas as a time for questionable consent, Christmas as an opportunity for role-play), Christmas as a time to mitigate famine by buying things stands apart. We are speaking, of course, of the monstrous amalgamation that is “Do They Know it’s Christmas?”

About the song itself, what can really be said? It’s not very good, something agreed about by Bob Geldof himself, despite his serving as the Janus-faced combination of Phil Spector and James Cameron for the whole Band-Aid enterprise. Lyrically, there’s enough “Africa is a country” casual colonialism to make even Hegel blush, and musically, apart from the sampled intro, it’s basically just a strung-together series of hooks, the better to earworm itself straight into your brain. For all that (and I do mean for all that), “Do They Know…” deserves to rise to the top (or sink to the bottom, perhaps) of this bracket, precisely because musically, conceptually, politically, it is, in a hideous way for an anti-famine scheme, the absolute culmination of Thatcherite/Reaganite cultural world-building, a hedonistic, maximalist explosion of sheer mediocrity that sinks its teeth in and refuses to let go, all in the name of doing good. I don’t, unfortunately, have a funny or sad or poignant personal story to convince you, as I was -5, and I don’t think this song had any appreciable impact on the people who would become my parents, extended family, friends, or teachers. It was not part of my childhood Christmas experience–we were a Nat King Cole and Harry Connick, Jr. family. It is a coincidence, although perhaps a significant one, that the first Christmas I really became aware of its existence was after I was well on my way in my PhD, and so could reflect on the Band-Aid project while driving through the drought-stricken fields of Fresno County, California, noting that despite the critical lack of water, there was no critical lack of food, of excess, of money. What I can offer is a wild trip down the roads of British cultural history, imperial identity, and neoliberal morality that lands squarely at the door of Sarm West Studios in Notting Hill, 8 November 1985, and if that’s not the true spirit of Christmas AND March Fadness, I’ll surrender my Duran Duran fan card.

To the credit of Geldof and Midge Ure, a significant part of the song’s weirdness is that it has to square something of an absurdly impossible circle: a Christmas-themed pop song about a hideous drought that led to a massive famine, and the unimaginable human suffering that was, at the time, an ongoing result. I am neither a professional nor amateur songwriter, so my bafflement means little, but I truly don’t know how one would manage such a thing successfully. Geldof managed by basically jettisoning anything that might be considered actual Christmas imagery, and just adding “Christmas” in front of things evocative of his understanding of the moral situation of the famine. We’ll come back to the idea that Christmas is about how our “world of plenty” is what causes “smiles of joy” and thus our ability to “throw our arms around the world…at Christmas time” (I know you can hear the line), but first, I want to talk about darkness and light.

The first lines in the song establish a moral grounding, as well as the fundamental absurdity of the imagery at play. Apparently Christmas is “no time to be afraid,” because it’s then that we “let in light and banish shade.” Facile rhyme aside, it’s an odd sentiment for a holiday that occurs when 87% of humanity is experiencing it’s least amount of daylight, not to mention the fact that the idea of “bringing light in” is a weird whole-cloth invention of Geldof and Ure, not being part of Christian or secular images of Christmas. There’s more than enough preexisting imagery of Christmas as a time of plenitude in the face of winter deprivation, of charity, of community, of peace, of hope, why this strange insertion of a light/dark dichotomy instead of something both more traditional and more apropos? The key is in a slightly later line, where we learn that apparently Christmas bells are really “clanging chimes of doom.” This slightly absurd and very discordant phrase, coupled with the light and dark imagery earlier, sets off a rhyme with a much older English (yes I know Gelforf and Ure are Irish) call to social justice, William Blake’s “And did those feet in ancient time,” more commonly known in its setting to music by Hugh Parry and Edward Elgar as “Jerusalem.”

Written around 1804, Blake’s poem is a consideration of a supposed traditional belief about Jesus’s “unknown years” (the time between ages 12 and 29 that are not mentioned in the canonical Gospels), in which the Son of God decided to take a few gap years in England for some reason. The poem is a stark call to revolution, bemoaning the deleterious effects of the Industrial Revolution on the landscape and people of England, and reminding readers that the Kingdom of Heaven (the new Jerusalem) comes only to those who work for it. In a cruel irony, Blake’s plea for the rejection of simpleminded nationalism has largely become a patriotic English symbol, played at the last night of the Proms alongside problematic “Rule, Brittania,” and inspiring the title and treacly closing scene of Chariots of Fire. Most importantly here, it inspires laughs that England’s unofficial national anthem contains the phrase “dark Satanic mills.” [1] While it’s true that it’s never not funny to witness hundreds of English people people singing the word “Satanic” in unison, the reduction of the song to an English national anthem is deeply depressing. Blake’s whole point is that the darkness, the devilishness, is something internal to be combatted. One’s duty is to use one’s mind and indeed one’s sword to fight the evil within, in this case the destructive exploitation of industrial capitalism. This is not an anthem for the likes of Boris Johnson, and yet here we are. It seems like a fundamental component of jingoistic nationalism to take the cultural artifacts and completely upend their messages in a project of incorporation–“England isn’t specially blessed, evil is within and must be combatted” to “England is specially blessed, evil is without and must be kept out.”

The rhyming imagery between Blake’s dark Satanic mills and Geldof and Ure’s banished shade and clanging chimes of doom underscores the tension of what is an essentially British project to mitigate the devastation of a famine in the Global South. Turning Blake’s logic inside out, the song claims that everything is just fantastic here, so why not help with the terrible reality of what it is be one of the “other ones” out there? In this global understanding, places like Britain and the United States are just natural sites of plenitude, while “Africa” is naturally a site of suffering, with no rain and no food. This view of course completely ignores the geopolitical reality of famine. While we imagine things like droughts and resulting famines as natural occurrences like hurricanes or blizzards, the reality is that human contribution does greatly affect the outcome of such climactic events, at least in terms of mortality. First, industrialization has greatly altered weather patterns, particularly for extreme events, and so droughts and floods in particular are far from “perfectly natural” occurrences, with the fault laying primarily at the feet of long-time industrialized imperial nations. Second, famine specifically was a specialty of the British Empire. During the Great Irish Famine, Ireland remained a net exporter of food to England, sending enough butter alone across the Irish Sea to meet the caloric needs of every adult in the country. The deaths came as a result of the British refusal to provide adequate aid and support, motivated by explicitly genocidal Social Darwinist beliefs. This state of affairs was also seen multiple times in British India, where a series of famines between the mid-nineteenth century and 1947 resulted in between 5 and 10 million deaths, almost entirely due to the refusal of British colonial administrators to provide aid, while India continued exporting massive quantities of food. In the last, the Bengal famine of 1943, it was Winston Churchill’s policies, motivated by the exact same desire for racial extermination that he was nominally fighting in Europe, that resulted in 3 million deaths, almost purely as a result of Britain extracting resources to feed itself at the expense of its colonial subjects. England’s “green and pleasant land,” as Blake calls it, had in fact managed to turn the rest of the world into a dark Satanic mill, something that “Do They Know…” perhaps understandably glosses over as it tries to paint Britain as the source of ease and abundance in a way that is disconnected somehow from the “world of dread and fear” that is “outside your window.”

To his credit, Bob Geldof probably didn’t know most of this, and did in fact try and do something to help. What I think is damning, in an impersonal, ideological way, is that when he saw a BBC report about how white nurses were “forced” to play God with Ethiopian lives due to lack of supplies, he rushed to his Rolodex and got on the horn with the rich and powerful not to demand their money, or policy changes, or even pure publicity, but to create a product to sell. Britain’s greatest musical talents (and Duran Duran) were asked to contribute their time and skills to a big pile of mediocrity so that consumers could be tempted to Give By Consuming. What was the point of Phil Collins’s perfectionist drumming technique except to add to the branding? Boy George’s name was so important that Geldof forced him to catch a last minute Concorde from New York, a ticket that would have been several times the cost of a conventional airliner while producing more than three times the carbon emissions. In terms of political showdown, it makes sense to imagine a tense standoff between the “I don’t mind apartheid actually” Thatcher government and the outraged Irishman trying to do good in Africa. Instead, Geldof’s big dustup with Maggie’s crew was to force them to remove VAT (Value Added Tax) from the single in order to move more units, meaning that consumers wouldn’t have to make even paltry contributions to the NHS or other beleaguered social services with their purchase of the Band-Aid 7”. One of the most damning political gotchas I’ve ever heard is an anecdote about a reporter asking Thatcher about her most important achievement, to which she responded “Tony Blair.” While the VAT fight was portrayed as Geldof defeating the evil racist PM, it’s hard not to see Thatcher smiling at the supposed liberal beating her at her own tax-destroying game. More than the coke and booze laced recording party, more than the media frenzy, more than the big hair and clashing patterns, the most ‘80s thing about “Do They Know…” is the way that it moved famine into the neoliberal era. Goodbye to famine-as-genocide, hello to famine-and-famine-relief-as-product.

Contrary to what my perhaps overly-strident tone communicates, I don’t actually hold “Do They Know…” or Geldof, or Band-Aid, accountable for political failures. It is, after all, a pop song, and a pop song that was, however, oddly, trying to do some good in the world. It would be absurd to really expect pop songs to be serious educational opportunities, even though they sometimes can be. Most pop songs, including most of my competition here, is about mashing body parts together, and that’s just fine. What I do think is important is that “Do They Know…” is deeply, deeply symptomatic of the emergence of a “progressive” neoliberal geopolitical outlook. “Do They Know…” is part and parcel of the process by which Thatcher and Reagan’s world became Blair and Clinton’s, the hard edges of overt racism sanded off into concern about “crime and poverty,” the explosion of the charity industry, and soft (and yet still quite hard) hierarchies and borders of Davos as opposed to apartheid-era Johannesburg.

Frankly, this song deserves the crown here if only because none of the competition feature the combined talents of Sting, Bono, Spandau Ballet, Duran Duran, George Michael, Heaven 17, Boy George (unsurprisingly looking incredible), Phil Collins (unsurprisingly looking like a huge nerd), and Kool and the Gang (entirely on accident). Find me another assemblage of British New Wave talents, I dare you. Beyond that conventional story of ‘80s excess, though, this song, and its status as a true “one hit wonder,” draws out the real truth of the 1980s as a political and cultural moment–a time of transition, where the Powers That Be were figuring out how to keep doing evil while looking like they were doing good to a generation of people seemingly less inclined to go along with the social mores of the 1950s, the Reagan-Clinton pipeline. It may not be a good song, but damn if it’s not the ‘80s in one, condensed, absolutely absurd form. Feed the world.

[1] NB, Britain’s national anthem is God Save the King, but the four constituent nations also have unofficial national anthems to be played at sporting events etc. England’s is generally Jerusalem, and it should be no surprise that the Scottish and Welsh anthems explicitly state how much they hate the English.

Andrew Bethke is an academic malcontent, PhD candidate in history, and currently driving a bus for pay. He was was slow to appreciate the contribution of synths to pop, but this picture proves he was in fact alive in the ‘80s, however technically.

nicole walker on “somebody’s knockin’”

Before blue jeans were invented, there was no such thing as sex. It’s possible that people mated, or bred children, practiced coitus, had a quick ‘tiff,’ or knew each other in the biblical sense or even made love, but they did not have sex until 1873 when Jacob W. Davis and Levi Strauss patented the denim pants with copper riveted pockets.

In my mom’s Toyota Corolla Wagon, my only pair of Jordache Jeans wearing thin against the vinyl seats, I reached over and turned up “Somebody’s Knockin’” whenever the song came on the radio. I liked the questioning in the song. I liked the irony of somebody asking the lord if they should let the devil in.

Somebody's knockin'

Should I let him in?

Lord, it's the devil

Would you look at him?

I've heard about him

But I never dreamed

He'd have blue eyes and blue jeans

I probably liked the idea of the devil. I’d grown up in Salt Lake City, Utah where the devil was not allowed. Well, unless you were a heathen, as I was, and you let him in. The 80s were the years of paradox. Just having taken all their clothes off at Woodstock, people started to put their clothes back on. As in Victorian times, a little bit of ankle showing electrified the lust lying underneath the suit vest and pleated pockets, in the 80, a little push back against the “hey, let’s get it on,” of Marvin Gaye—

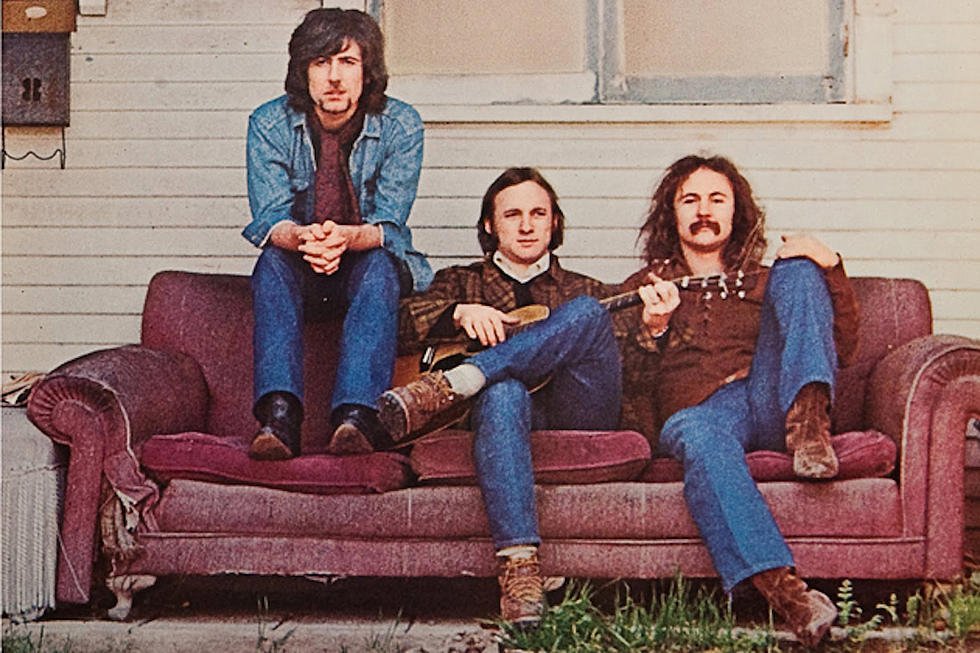

[note the full-length denim]—or the “if you can’t be with the one you love honey, love the one you’re with”—

—[note the Levi’s]—of the 60s and 70s bought a little tension between the sexes. A yo-yo effect. Tug-of-war, or yo-yos, or that move at the end of Grease when Olivia Newton John walks toward John Travolta, turns away, then turns toward him again, pushing and pulling Gen-X’s sexual psyche this way and that, inviting my sisters and me to sing Fire very loudly in the front seat of our mom’s Toyota along with the Pointer Sisters:

I'm ridin' in your car

You turn on the radio

You're pullin' me close

I just say no

I say I don't like it

But you know I'm a liar

'Cause when we kiss, ooh

FireLate at night

You're takin' me home

You say you want to stay

I say I want to be alone

I say I don't love you

But you know I'm a liar

'Cause when we kiss, ooh

Fire

[Note. Jean-clad all three.]

I could talk about the rapeyness of both “Fire” and “Somebody’s Knockin’” songs. Someone knocking at your door, tapping your phone, “coming on strong,” is not an auspicious beginning to a relationship, (Also he’s the devil, so.) How can we teach our daughters that no means no when we’re singing, ‘but my words, they lie, because when we kiss, ooh, fire,” although the ‘when we kiss’ suggests probably consent.

Bruce Springsteen has a lot of songs about fire. “Hey little girl is your daddy home? Did he go and leave you all alone? Oh oh. I’m on fire.” Also inappropriate sexual content! And yet, it’s hard to get mad at Bruce Springsteen. He is many things to many people, rapey, so far according to the #metoo movement list of men who are, and who abusedly used them, dicks, Bruce isn’t one of them.

Bruce Springsteen’s Born to in the USA album cover features what we’re led to believe is Bruce Springsteen’s backside in a pair of Levi’s, a red handkerchief stuck in his back pocket:

Released in 1984, this album screamed USA.

If you were like me and misunderstood the lyrics, this led you to believe that Bruce was 100% pro-Ronald Reagan and you couldn’t listen to his music any more. But still, that butt in those jeans, even if Bruce was too old for you then. Even if he was salaciously asking if your daddy was home. The well-jeaned ass signaled perfectly rock star and yet also, perfectly boy next door---both of which were dangerous, in the 80s.

In the 90s, people just started saying fuck in their songs and giving sexual advice, like Salt-N-Pepa singing,

Let's talk about sex for now

To the people at home or in the crowd

It keeps coming up anyhow

Don't be coy, avoid, or make void the topic

Cuz that ain't gonna stop it

Now we talk about sex on the radio and video shows

Many will know anything goes

[Bonus Denim and Leather]

In the 90s, the straights started worrying about AIDS and safe sex. In the 90s, it was probably time for women to quit the whole virgin/whore business. I didn’t have to pretend to be I was the innocent Sandy from Grease and or the leathered-up Sandy and multiply Danny’s denim-bound chills:

[Sandy’s all leather but Danny wears dark blue jeans]

In the 90s, I could be both. But in the 80s, a layer of repression over a layer of freedom, a layer of feminism over a layer of return a 50s sensibility made cutting through those layers complicated and maybe a little erotic. The 80s still reveled in a bit of ankle reveal. Now that sex had been invented thanks to blue jeans, now was the time to sing about sex and Levi’s, as often with as much alure and tension-filled seduction as your husky voice could make happen.

John Cougar,

pre Mellencamp, in 1982, sang of Diane’s blue jeans. Bobbie Brooks, a fashion line begun in Cleveland, were a kind of jean you could dribble off.

Suckin' on a chili dog outside the Tastee Freez

Diane's sittin' on Jacky's lap, he's got his hand between her knees

Jacky say, "Hey Diane, lets run off behind a shady tree

Dribble off those Bobby Brooks slacks, now do what I please.

“Doing what I please” in 80s speak, when you’re a kid, listening to the radio, sounds, from John Cougar’s lips, seems like it will go well for Jackie.

If there’s one perfect verb to describe how blue jeans come off, ‘dribble’ is that one. The way you can pull a bit of Levi down with one tug, but have to stop and readjust your hands further down to tug again. Blue jeans don’t slide unless you’re already lying on a bed and your hips are already in the air:

(not that they’re that much easier to put on than tug off). It’s possible then, in one tug, with each hand holding denim at each ankle, to remove them in one fell swoop, but that’s advanced jean-removal and not something you can do behind a shady tree.

My friend, Rebecca Campbell, painted a giant canvas as I posed, lying on a blanket. My now-husband, if you look in the background, buttons his Levi’s. She named the painting “Jack and Diane.” I wondered where I put my Levi’s.

Some bands were early to connect sex and jeans. Fleetwood Mac, donning mostly blue jeans,

asked to “won’t you lie me down in the tall grass and let me do my stuff?” in 1977, letting it be known that women could do stuff in tall grass too. In 1978, Neil Diamond—

—argued that sex kept us safe from the forthcoming capitalism explosion that would come to define the 80s. In Forever in Blue Jeans, he’s offering a choice—the sexy, seductiveness of John Cougar’s, Terri Gibb’s, Olivia Newton John’s, and Bruce Springsteen’s Levi’s OR let people like Gordon Gekko, who distinctly does not wear Levi’s, in the film Wall Street become our destiny:

Money talks

But it don't sing and dance and it don't walk

And long as I can have you here with me

I'd much rather be forever in blue jeans

We should have stuck with Stevie’s tall grass and Neil’s jeans but nope instead we put shoulder pads in our suit jackets and started taking our pants to the dry-cleaners.

Perhaps the heat manifested by the push and pull in the backseat of maybe-lovers in the 80s mirrors the push and pull between the 70s and the 90s. We were in-between sticking with Neil in our blue jeans and realizing that AIDS kills in the late 80s, early nineties. In the early 80s we’re in between sexual awakening and sexual matter-of-factness. Yes, she can only come when she’s on top, James the band plainly states in 1993:

[Black Jeans count as blue in England]

In the 80s, you didn’t say “come.” You said, “knock.” Or “let him in” or “fire.”

In the 80s people were hanging on the telephone with Blondie, calling 867-5309 with Tommy Tutone. Maybe the telephone itself direct dialed the devil. Or, as Terri worried in Somebody’s Knocking, maybe he tapped your line. We spent a lot of time on hold, weighing the consequences like Terri does, weighing the consequences. She has so many questions:

Somebody's knockin'

Should I let him in?

Lord, it's the devil

Would you look at him?

I've heard about him

But I never dreamed

He'd have blue eyes and blue jeans

The 60s and 70s promised free love. Then, AIDS happened and sex became expensive. Then Reagan happened and sex became not only expensive but repressed-ish.

David Bowie didn’t want things to be hard.

He wanted Blue Jean:

One day I'm gonna write a poem in a letter

One day I'm gonna get that faculty together

Remember that everybody has to wait in line

Blue Jean, look out world, you know I've got mineShe got Latin roots

She got everythingSometimes I feel like

(Oh, the whole human race)

Jazzin' for Blue Jean

(Oh, and when my Blue Jean's blue)

Blue Jean can tempt me

Gordon Lightfoot, like Terri Gibbs, understood the eroticism of the threshold. To be on the inside is to be fraught, conflicted, tempted, seduced, bedeviled. The back and forth of desire and inhibition rubs like denim between your legs.

Gordon Lightfoot warns against Sundown, coming around in the same way Terri Gibbs complains about the devil coming around in blue jeans. These temptations coming right up to your door—the 80s sounded the warning.

I can see her looking fast in her faded jeans

She's a hard-loving woman, got me feeling meanSometimes I think it's a shame

When I get feeling better, when I'm feeling no pain

Sundown, you better take care

If I find you been creeping 'round my back stairs

In the 80s, I was indoors, waiting for somebody to come knocking. The 80s were the waiting years. Waiting to be done with high school. Waiting for the bomb to drop. Waiting for tickets to a show. Waiting for my boyfriend to pick me up and waiting for my best friend to come back after putting me on call waiting. I waited to turn 16. I waited for grown-ups to see that I was practically an adult. I waited to get my first pair of Jordache, then my first pair of Calvin Klein, then Guess, and later Girbaud. Like the Pointer Sisters and Sandi and Terri Gibbs, I had quandaries about sex. But I also didn’t wait. I didn’t wait to pull the waistband fabric of my boyfriend’s 501s, unleashing all five buttons in one ripped motion. I didn’t wait to unbutton the four buttons of my own Levi’s.

Levi’s were sexual empowerment. I walked around the cabin in only my Tweed jeans, no top. While lying in the tall grass, I kept one leg of my jeans on. Wearing Levi’s, my then-boyfriend and I climbed on top of the big boulder we called the Rock that ran next to Little Cottonwood Canyon. I danced to Fugazi—

—in my jeans, devilishly grinding to Waiting Room, a guy’s Levi’s buttons cold against my back. Terri Gibbs’ may not have known who was knocking or talking or tapping her phone, but I bet the devil knows how to take his blue jeans, and mine, probably, off especially well.

Nicole Walker's hair takes too kindly to perms and hasn't curled her hair since 1985. For the past three months, in preparation for March Fadness, she has worn blue jeans every day. She answers the door for both devil and angel.