round 1

(4) joan jett, “crimson and clover”

BROUGHT DOWN

(13) hüsker dü, “eight miles high”

293-139

AND WILL PLAY ON IN THE SECOND ROUND

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/2/22.

david turkel on Joan Jett’s “Crimson and Clover”

“Joanie Jett! She’s got the greatest voice I’ve ever seen!” —DuBeat-e-o, 1984

I’ve named the play “Crimson and Clover” because I don’t know what it’s about. I want people to make up their own meaning, the way they do when they hear that song. I want them all to think about something different that’s true for each of them.

It’s 1998 and I bartend in a place called Hell and Joan Jett’s version is on our jukebox. Or “little Joanie Jett,” as we call her—an homage to Alan Sacks’ trash film, DuBeat-e-o.

When I ask customers what they think the song means, they tell me a dozen different things, as if the title itself were a sort of Rorschach. One says the song is about a girl losing her virginity. Another says that it’s clearly about shooting heroin, the blood mixing with the “honey” in a syringe. Still another informs me that Tommy James—the writer of the song—was a born-again Christian and that the crimson represents Christ’s blood and the three-leafed clover, the Holy Trinity.

The lead actor in my play, Tom, was of draft age in December 1968 when the Tommy James and the Shondells’ version raced up the charts. He tells me the song has always been about Vietnam for him: “blood and land, over and over again.”

My play is about none of these things. Though it’s written in three acts, which could represent the Trinity, I suppose. And it has some sex and violence in it. Also heroin. And camel spiders. And St. Francis and surfing and the C.I.A. Mostly it’s about a billionaire named Arson (played by Tom) who wants to become the first man in history to cross the United States, coast to coast, entirely underground.

It’s my first play and I’ve been in therapy since I started it. I ask my therapist—a Jungian—if he wants to know anything about what I’ve written. He doesn’t. “Isn’t it like a dream?” I suggest. “Couldn’t that be useful?” But he doesn’t seem to think so.

Tommy James claims to have simply woken up with the words “crimson and clover”—a combination of his favorite color and favorite flower—stuck in his head. But that story was disputed by Shondell drummer Peter Lucia Jr., who co-wrote the song. For Lucia, the title sprang from the name of a prominent high school football rivalry in Morristown, New Jersey (where he grew up) between the red-uniformed Colonials and the green-Hopatcong Chiefs.

And so, oddly, even at the ground-zero of the song’s creation, there’s dispute over what the words signify. Almost as if they were birthed twining a spell of some sort—weaving mystery and confusion into the air.

On the Songfacts message board devoted to “Crimson and Clover,” contributor after contributor offers what each insists is its sole, incontrovertible meaning. Kayla from Dallas writes, “The song is actually about a beautiful girl with red hair and green eyes, get it?” Rex from the ‘Heart of America’ begins his post, “It really surprises me that so few people have this right” before launching into the most painfully halting description of coitus, like a squeamish father tasked with the birds-and-bees speech.

However the title came about, the story of the song itself is well-established, if no less magical. As Shondell keyboardist Kenny Laguna tells it, the band had just lost their chief songwriter and the guys were pushing Tommy James to find somebody new, convinced he didn’t have the chops to write a radio hit himself. Five hours later, James and Lucia walked out of the studio with the recording of “Crimson and Clover”—James having played every instrument except drums on the track.

He then took the rough mix to WLS in Chicago, where he spun it for the head of programming as well as a top DJ to get their impressions. At some point during the visit someone at the station pirated a copy, and by the time Tommy James had returned to his car the single was on the airwaves in its raw, unmastered form, being hailed by the DJ as a “world exclusive.” Before Morris Levy, the infamous mobster who ran the Shondells’ label, could intervene, “Crimson and Clover” was already a hit and on its way to its ultimate destination at number one on the charts. Many who heard it that holiday season in 1968, thought James was singing “Christmas is over” on repeat.

At a Christmas party in 1998, an inebriated dancefloor collision results in my girlfriend tearing her ACL. We’re too fucked up at the time to know what’s happened. But when I wake up the next morning, she’s there beside me, crying in her sleep from the pain.

She’s been cast in my play as Looloo, a twenty-five-year-old recovering heroin addict whom Arson meets touring a new hospital wing. Looloo is a patient there because she skied off a mountain in an apparent suicide attempt. So, it makes sense that her leg might be in a brace, we reason. Sometimes things like this just have a way of working out.

“Do the math,” Lon from Providence insists. “It is a poetic masterpiece...about a plaid skirt...the girl he had a crush on in school wore...hence the colors maroon (crimson) and green (clover), and then the pattern over and over..........”

My girlfriend and I are among the half dozen or so co-owners of Hell, where, until the accident, she was also a bartender. She’s the real reason Jett’s 1997 retrospective Fit to be Tied is on the box, and why we frequently holler out, in our best Ray Sharkey impressions, “Joanie Jett! She’s got the greatest voice I’ve ever seen!” whenever it plays.

Sharkey portrays the title role in DuBeat-e-o: a movie director who’s on the hook to the mob for a new picture starring Joan Jett. In real life, director Alan Sacks (best known as a creator of Welcome Back, Kotter) had been hired to salvage botched footage from an attempted screwball movie based on the Runaways—the all-female, proto-punk band Jett founded with drummer Sandy West in 1975, just weeks shy of her seventeenth birthday. Sacks had fallen in with the L.A. Hardcore scene and his solution to the problem of trying to use bad footage to make a good movie, was to make an even worse movie about a megalomaniacal director’s fantasy of making a great one.

“See, I shot this film so that Joanie would come out looking hip enough to handle any situation. Understand?” DuBeat-e-o lectures Benny, the cough syrup-addicted film editor (played by Derf Scratch from Fear) whom he’s chained to an editing station at gunpoint. “I mean, that’s why I put her in every slimey, scummy situation of Mankind that I can think of, okay? I mean, the essence of my film—my film!—is that true talent, no matter where it comes from, has gotta come out—because it’s got fucking ENERGY! You understand?!...That’s why I’m the director! I got the vision, you prick!”

IMDB lists Jett as “starring” in DuBeat-e-o, but this is a Bowfinger-like deception, since she only appears by way of the archival footage Sacks was hired to edit, and as a picture adorning a wall in DuBeat-e-o’s seedy apartment. More accurately, Jett is hostage to the movie, her bottled image coopted to serve its baser designs; her ever-tough performance chops fronting the Runaways cut to look as if she’s delivering these efforts to please the leering countenance of The Mentors’ El Duce (who plays his slimeball self in the film).

And yet, perversely, it all works. Moreover, it works just as DuBeat-e-o, at his most deranged, said it would: Jett’s hipness—her ENERGY—rises above it all, untouched and unsullied. And the movie, either in spite or because of its many flaws (it’s really impossible to say which), truly exalts her.

In the 2018 documentary Bad Reputation, Jett—its ever-inspiring subject—avoids any mention of Sacks’s film by name, but merely shrugs it off as “some weirdo porn movie.”

Before I started tending bar at Hell, I knew next to nothing about Joan Jett, outside of “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll”—a single that peaked when I was eleven years old and inking “O-Z-Z-Y” across my knuckles.

I didn’t know about the Runaways or Jett’s affiliation with the Sex Pistols. Didn’t know that she produced the first Germs album and music by Bikini Kill. Or that she and ex-Shondell Kenny Laguna—her longtime collaborator and Blackheart producer—were forced to shill her hit-laden solo debut out of the trunk of Laguna’s car after it was turned down by twenty-three labels. In short, I didn’t know that Joan Jett was punk before punk and indie before indie.

But by 1998, not only do I know these things, forty-year-old Jett has recently turned up in a black-and-white commercial for MTV, flipping off the camera and sporting the close-cropped platinum-dyed hair that will become as iconic to that era as her black shag was to the seventies. She’s been going at it hard for more than two decades at this point, only to emerge looking fitter, tougher, sexier, more otherworldly than ever before, and I am becoming obsessed.

“And there was Joan in the black leather jacket,” Laguna says of their first encounter at the Riot House on Sunset Boulevard. “The way I remember it, there was razorblades hanging from it. And...I just never seen anyone like this. I was like, ‘Whoa! What is this?!’ And...I think I loved her right away.”

Ahhh, well, I don’t hardly know her...

“A little quiz for the Peanut Gallery,” posts Alan from Providence on Songfacts. “Crimson is my color and clover is my taste and aroma. What am I?” he asks, before adding, with a tacit wink, “And there is a reason Joan Jett loves this song.”

But I think I could love her...

Laura from El Paso concurs: “I have to say that when Joan Jett sings this song, for me it is impossible not to feel it takes on a whole new meaning. She is singing about ‘her’ and how she wants crimson and clover over and over.............”

And when she comes walking over

I been waiting to show her... \

Joan Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” arrests us, not only for those parts of the song she’s altered, but also for what she’s kept in place: the pronouns of the singer’s object of desire. Though Jett has said this decision was about preserving the integrity of the rhyme scheme, the seismic impact of hearing one woman sing so intimately to another—unprecedented on popular radio in 1981—can’t, and shouldn’t, be overlooked. Not because the choice scandalized certain listeners (I mean, seriously, fuck them), but because for many others this was a revelatory and liberating event.

As Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna puts it, “The first time I heard Joan I was in the car with my dad and it came on. It was ‘Crimson and Clover,’ and I heard that voice, and I was just like, ‘Who is this person?’ And then, when she would get to the pronouns and say, ‘she,’ I got really interested.”

At the same time, I think it’s important to take Jett at her word as a no-nonsense rock- and-roller simply working in the service of a great song. Certainly it’s true that, where rhyme was no impediment, she proved more than willing to make heteronormative adjustments. Case in point: her most famous cover off the same album, the Arrows’ 1976 tune, “I Love Rock and Roll”: “Saw her standing there by the record machine” became “saw him standing there.”

But what’s true in both cases is that Jett’s persona animates and subverts each narrative equally. Speaking for the eleven-year-old that I was when I first heard “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll,” it was a novel and noteworthy experience to be confronted by a sexually aggressive woman describing her recent conquest of a teenage boy in such tough, conversational terms. Like Hanna, or Kenny Laguna, I distinctly remember thinking, Who is this person?

Jett describes her own approach to inhabiting songs this way: “Part of it is having fun, and part of it goes back to...being able to do everything. When you’re singing songs about love and sex, you want everyone to think you’re singing to them. Whether you’re a boy, a girl, a woman, a man—whatever you’re into, I can be that.”

My, my such a sweet thing

Wanna do everything

What a beautiful feeling...

“The greatest voice you’ve ever seen”—that superlative from DuBeat-e-o—has never been showcased to greater effect than 1982’s “live” performance video of “Crimson and Clover.” At minute 1:28, Jett seems to be singing in harmony with her own eyeballs. Yes, sing the eyes, you know exactly what I mean... I would argue that as much as keeping the word “her” matters to this cover, the potency of Jett’s rendition hinges on her phrasing of the word, “ev-er-y-thing.”

What’s brilliant about Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” is the way she both queers and straightens the song. Gone is the drippy vibrato and underwater warbling which threatens to make the original a relic of Psychedelia. In their place, Jett and Laguna have punched up the guitars and amplified the dynamic interplay between the breathy, epiphanic verses and the riotous bounce of its instrumental breaks. In live performance, at the dramatic crescendo—Yeah!—Ba da! Da da! Da da!—Jett never fails to let go of her guitar and raise her arms fist high toward the audience. “Crimson and Clover” is an anthemic rocker, as she embodies it—a song about connection, celebration, ecstasy.

But what truly distinguishes Jett’s version from the Tommy James and the Shondells’ original, is that Jett actually knows what she’s singing about; Tommy James didn’t have a clue.

“People ask me what it means?” James told a Youtuber who calls himself the “Professor of Rock” in a 2019 interview. “Two of my favorite words that sounded very profound when you put them together. And just a three-chord progression, backwards.” For Jett, on the other hand, the meaning is clear. In Bad Reputation, she envisions the song from the perspective of the woman she’s singing to: “‘Oh my God, she’s gonna take me home and fuck the shit out of me!’ That’s scary!”

I don’t make this comparison to disparage Tommy James; cluelessness is possibly the single greatest feature of his music. He recorded “Hanky Panky”—his first number one hit and one of my all-time favorite rock-and-roll tunes—having only heard a garage band’s cover of the original and remembering almost none of its lyrics. His chart-topper “Mony Mony,” from March of ’68, cribbed its title off the acronym emblazoned atop the Mutual Of New York building, which loomed outside the window of James’ Manhattan apartment. In both cases, his ability to imbue nonsense words with infectious energy and devilish intentions earns him Kenny Laguna’s praise as “the Led Zeppelin of Bubblegum.”

With “Crimson and Clover,” however, James needed a song that would do the opposite— launch him out of Bubblegum’s playground on the AM dial and into the burgeoning FM market.

And while he loves to tell the story of how the title arrived in his sleep and how the song was a deus ex machina for his band (“I think my career would have ended right there with ‘Mony Mony’ if there wasn’t ‘Crimson and Clover,’” he told It’s Psychedelic, Baby in a 2013 interview), the real truth is that Tommy James had spent nearly two years clocking an impending shift in the musical landscape. At an earlier point in the same interview, he describes the moment in February 1967 when he heard “Strawberry Fields Forever” crossover to an AM Top 40 station: “That really left an impression on me.” A new audience was emerging for whom Pop’s infectious energy was not enough. They were hungry for something beneath the surface.

Or, at least, the suggestion of it.

Not to be outdone by the Songfacts sleuths, I have my own admittedly less romantic view of the real meaning behind “Crimson and Clover.” Whether consciously or not, the title is a “Strawberry Fields” analog. Red and green, verdant and evocative—Crimson and clover, over and over is Tommy James’s Strawberry fields, forever.

This suspicion only solidifies with a listen to the whole Crimson and Clover album, which wears the influence of that particular Beatles’ song pretty thin over its ten tracks. "Hello banana, I am a tangerine,” Tommy James sings at one point, sounding like a narc trying to bluff his way onto the Psychedelic school bus.

But look again at the same three songs: “Hanky Panky,” “Mony Mony” and “Crimson and Clover.” All three open on an image of a woman in motion. All three turn on a chorus of indefinite but suggestive meaning. What truly separates them, and what also separates Bubblegum from Psychedelia (“Sugar, Sugar” from “Mellow Yellow”) is that the former uses innuendo to hint at a song’s true meaning, whereas the latter employs it to the opposite effect— suggesting that the song’s meaning is deeply buried and perhaps not even fully available to everyone.

All of which is to say that, while Tommy James certainly knows how to inject a song with implied meaning when he wants to, with “Crimson and Clover,” he is deliberately trying not to say anything. It’s a masterpiece of indirection. Like a shell game with no pea.

Stage lights rise on a young man hanging upside down, his head in a bucket. This is the character of Jeffery, the surfer in my play. He’s been imprisoned in an unnamed country by fascist goons who have mistaken him for a writer. He hangs like this for a few beats, and then his interrogator enters and grabs him up by the hair. That’s when the soundboard operator cues the song: Ahhh...well, I don’t hardly know her...

Joan Jett’s “Crimson and Clover” kicks off act two of my play. This is the real reason why I’ve chosen the title—I want the song to feel like it’s stitched into the very fabric of the text, so that no one will mistake it for a directorial or sound designer’s decision. Like DuBeat-e-o, Alan Sacks, Kenny Laguna, Kathleen Hanna, I want Joan Jett’s bottled light to illuminate my dim interiors; I want to claim some of that impossible energy of hers for myself.

But my director has other ideas about the power source we need to tap into for our production. A week before we open, he introduces us to Robert, his guru—a professor from his grad school days. Robert speaks at length in a haughty British accent on the subject of “vibrating at a different frequency”—a discipline which he believes, once mastered, renders an actor utterly captivating to audiences.

We’re gathered in a circle where the only language we’re allowed is the single syllable, “bah!” and we’re instructed on ways to “direct our sound.” First, off one wall. Then two. Then off two walls and through the window out into the street, like a bullet ricocheting. Bah! BAH! “Put your bah into your chests,” Robert tells us. Bah! “Now into your stomachs!” Bah!

I’m afraid to even look at my girlfriend, there in her leg brace across the circle from me. This is everything I promised her theatre wasn’t. The total opposite of Punk rock.

“Now, put your bah into your left foot,” Robert, the guru, prompts me, dropping to his knees so that he can rest his ear just below my ankle.

“Bah!” I shout.

He looks up and says in earnest, “Don’t yell. It’s not about volume. It’s about putting your voice into your foot.”

The next day, he takes the cast to a mall, where, at full voice in front of the Cinnabon, he describes the milling shoppers as “dead people.” Our job as high priests of the theatre, he informs us, is to remind them all what it means to be alive.

When Tom tells the guru that he finds the mall patrons “electric,” he is banished from the inner sanctum. Meanwhile, my girlfriend has hobbled off with one of the other actors to get stoned in the parking lot.

Eventually, I too shuffle away in despair and embarrassment. The guru’s visit has cost us two thousand dollars and we can no longer afford the boat we need for the climactic third act scenes on the underground river. It’s just as well. I’ve lost all faith in my play by this point. All my big ideas have turned into mush. The monologues I was so proud of, despite all my actors’ best efforts, ring false and contrived.

There’s only one scene I care about anymore. Over the run of the show, it will be the only scene I consistently emerge from the wings to watch. I wrote it in five minutes and thought nothing of it at the time. It’s just a breakfast scene with the whole cast present. Everyone gathers in the kitchen, trying to start their day and pass the butter around the table. Arson and Bell, the scientist, discuss plans to launch his underground journey from the secret lab she runs beneath Mount Weather. Ed, the CIA operative, tells a crass joke to Looloo and Benedict—a psychic who’s recently been helping Arson communicate with the dead.

Jeffery is the last to enter. He’s been in bed for days, horribly sick from his ordeal. He’s shaky on his feet and not really certain where he is.

There’s something about the rhythm of this sequence I got right. The butter, the stray fragments of dialogue and competing conversations. The entrance itself, which isn’t clocked by everyone at the same time, so that it’s like a musical breakdown with all the instruments cutting out one by one. The particular quality of the silence that follows, as Jeffery stands there swaying, and Looloo slowly rises to meet him. There’s something about the way the actors have to extend themselves to fill the gaps in this scene; that’s where the life is, I’m starting to understand, in those gaps.

This is my first real piece of theatre. No one thinks twice about it but at least I’ve figured that much out. In performance, you don’t hardly know what you’ve written until someone else tries to make your words their own.

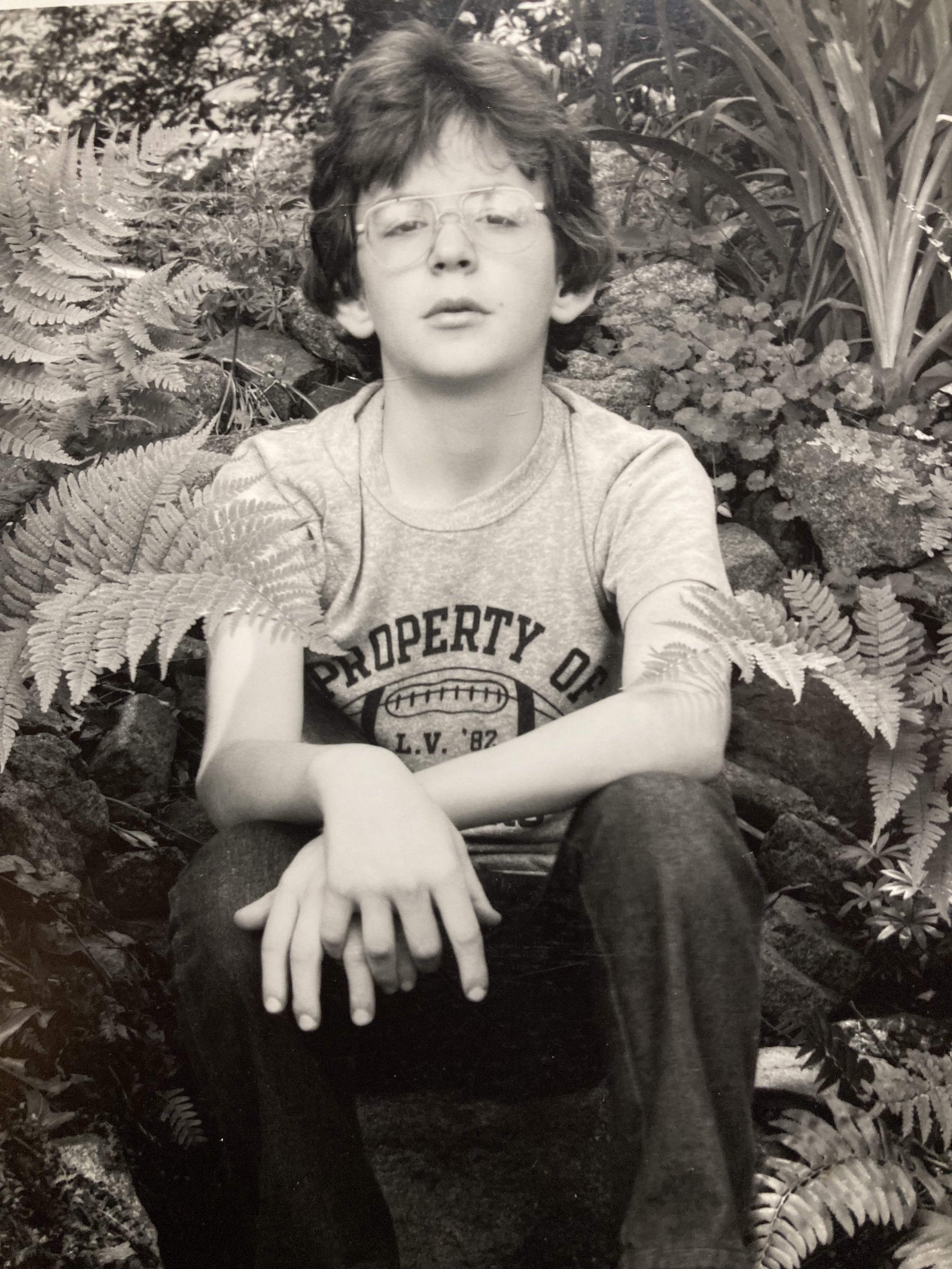

The author in 1982, the year Joan Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” peaked at #7 on the Billboard Hot 100. Captured here in the wilds of New Jersey, without a clue in his mind that he is headed straight to Hell. And from there, eventually, Oregon. He will pick up bartending and playwriting along the way and would be pleased to know that he’ll one day land a gig writing about vampires for television.

DO YOU REMEMBER? jeff sirkin on Hüsker Dü’s “eight miles high”

“When I hear his music I want to copy it. Not note for note, but in its spirit.”

—John Coltrane, on Ravi Shankar

“If it’s not urgent, why bother with the relaunch?”

—Rosa Alcalá, at breakfast the other day

I was a Junior in High School and I looked it, but I’d walk into McLevy’s Pub lugging in the mixer or amp, and the bouncer wouldn’t even look up. I’d help my brother, Marc, set the speakers on their stands and adjust the mix while the early drinkers watched apprehensively. At 8:00, I’d find a seat off to the side, and Marc would grab his guitar and head up to the mic.

It was 1987, and my musical life still revolved mostly around the music Marc and I shared—Neil Young; Simon and Garfunkel; the Who; Crosby, Stills, and Nash—and the music I’d hear on Cincinnati’s classic rock behemoth, WEBN, “The Lunatic Fringe!” WEBN had emerged out of the late-60s counterculture at the dawn of the FM era, making itself a home for what was at the time still a very controversial genre, rock. But it had become over the years, by playing essentially the same classic rock hits on repeat—the Doors, Jethro Tull, the Byrds, Pink Floyd, etc.—a commercial powerhouse whose primary product was nostalgia for its own storied past. The only new music they’d play would be the latest from an aging 60s rock act (Jefferson Starship, for instance) or a song that somehow referenced rock’s glory days (“Summer of ‘69”). But, hey, the lunatic fringe! For me and my friends and everyone we knew in the largely white suburbs, this was the only station on the dial, part of the uniform, like the white sneakers and Dark Side of the Moon t-shirts we all wore. The Who, Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, Neil Young. What else was there? The Cure? Siouxsie Sioux? The Smiths? Not even a rumor. Hüsker Dü? What’s that?

Marc had Thursday nights at McLevy’s—a generic wood-paneled “pub” set next to a comedy club a couple miles from home. For fifty bucks a night, he was one of the bar’s stable of acoustic-guitar wielding entertainers, playing a curated selection from the songbook of 70s singer-songwriters. Marc was good. Really good. Especially on the mellower songs that fit his pure, clear voice and quiet temperament. He’d spent years learning the dozens of tunes he could then play by heart, and it showed. The only problem was that he was in school at Miami U., in Oxford, forty-five minutes away. So, every Thursday after school, I’d drive my ancient Olds 98 up to Miami, pick him up, turn around, and deliver him—and his gear, and me—to the bar.

At McLevy’s, the idea was to get the junior executives and secretaries and restaurant hostesses and fitness club trainers singing along and drinking to the upbeat hits of by-gone troubadours—Jim Croce, Harry Chapin, Paul Simon—and to a handful of classic rock mainstays (“Paint It Black,” “Pinball Wizard”) arranged for acoustic guitar. Marc had gotten into the whole scene just because he liked to play and sing, and he was never very interested in being a showman. But he knew the drill, and during a good set he might get into a rhythm with a particularly engaged table or two, joking around between songs, playing their requests, etc., and on these nights I could see he was having fun. There were bad nights, too, of course: drinkers asking him to turn it down, or complaining about the reverb on the vocals, or begging him not to play some song or another. Many nights, though—and it really didn’t matter how good he was—the drinkers would act almost like he wasn’t there, with little more than a polite clap or two now and again to acknowledge his presence. It didn’t matter. He’d play on, straight-faced, unfazed.

It’d be late by the time he was done, so he’d stay the night at home, and the next day after school we’d drive west around I-275 and then up Route 27 to Oxford. We’d listen to WEBN along the way, of course, until the signal gave out to static, somewhere along 27, and then drive in silence until we got to Oxford and Miami U., with its red brick and manicured quads and his rundown fraternity house, where I’d drop him off and then head home.

*

One Friday, having dropped Marc off at school and heading back down 27, grey hills speeding by, grey sky pressing down, grey suburbs and grey weekend ahead of me, I was having trouble getting WEBN. Static. On a whim I flipped the dial to 97X. Broadcasting out of Oxford, Ohio, 97X was the only station in the region at the time playing independent rock—bands you mostly couldn’t hear anywhere else, and whose names I would not have known: the Fall, the Replacements, the Dead Milkmen, Siouxsie and the Banshees, Erasure, New Order, Camper Van Beethoven, Echo and The Bunnymen, the Sugarcubes, and hundreds of other alternative and punk and postpunk and hardcore bands not affiliated with corporate labels. I’d heard of the station but never listened, as the signal just didn’t carry clearly into suburban Blue Ash, where I lived. How could it? Here, on the road between Oxford and Cincinnati, though, in the grey afternoon, I knew the signal would be clear.

And I was hit with what could have been a jet engine. A blast of guitar so fierce, so visceral, so present and alive, so alarmingly and beautifully distorted in a way I’d never heard before, I nearly drove off the road. I was no stranger to rock guitar. I loved the Who and Jimi Hendrix’s Axis Bold as Love, I knew the Ramones. But, I’d never heard anything like this. I turned it up.

The opening riff was familiar but I couldn’t place it in the context of the jagged roar ripping through the speakers. A riff that had surely been the droning background for a thousand sunburned days drowsing by the municipal pool, high on the sickly-sweet scent of suntan lotion, hopeless desire, and an endlessly repeating loop of classic rock. I turned it up again as the vocals came in. A lyric I knew from a thousand sad nights falling asleep under the glow of my clock radio. Here, now, however, floating along the highway in my hand-me-down boat of a car, familiar as the tune was, everything about it was different. Jagged, raw, and fast, stripped bare of the dust and grime of decades, all the dead weight of a dying past cast aside, it had been broken down and made anew. Screamed where the original was serene; laconic where the original was overwrought; defiant where the original was foreboding:

“Eight miles high,” Bob Mould howled from an alternate universe, somehow recalling the familiar melody through the roar, “and when you touch down...”

Chills running through me, I cranked the volume higher, and for three minutes was transported to this new world. Destruction and beauty; rage and regret; a defiant growl against a world of always diminishing returns. I was flying. It didn’t matter what lay ahead, though I knew the static I’d find there. What mattered was the flight I’d found myself on.

*

The Byrds, whose first hits were folk-rock covers of Dylan’s “Mr. Tambourine Man” and Pete Seeger’s “Turn, Turn, Turn,” released their most famous tune on March 14, 1966. Written primarily by Gene Clark, “Eight Miles High” both marked the end of the original line-up (Clark would quit soon after the song was released, his fear of flying ironically cited as a reason) and a new beginning for the band, and for rock generally, as it was the first rock song to incorporate motifs and structures from Indian raga and avant-garde jazz. (Beating out the Beatles’ “Tomorrow Never Knows” by five months.) The track was also quite controversial due to its then shocking instrumental interludes and the (mis)perception that the title referenced drug use and was widely banned from radio play. Loosely, in fact, about the band’s disastrous first UK tour in 1965, the song is known for its opening instrumental section built around bassist Chris Hillman’s repeating bass riffs and Roger McGuinn’s ringing 12-string guitar improvisation intended to emulate Ravi Shankar by way of John Coltrane’s “India.”

While one can discern in the lyrics direct references to that dismal UK tour, the song is really more abstract than specific, the lyrics in broad strokes suggesting a generalized alienation in a cold world of storms and shadows. “Eight miles high and when you touch down / You’ll find that it’s stranger than known.” And, “Nowhere is there warmth to be found / Among those afraid of losing their ground.” But, while the lyrics are foreboding, the song for me really turns on the narrative suggestion that we have not yet touched down—the world described beyond the opening line is the future, it exists only as a possibility. Which leaves the potential for hope.

It’s a classic, for sure, and deservedly (I think), with its intense instrumental interludes, unique structure, and tight, moody harmonies. But, though controversial when it was first released, by the mid-eighties, it had become just another classic rock hit on permanent rotation at bloated and middle-aged rock stations like WEBN, wallpaper for a world that was sliding into a permanent state of nostalgia.

*

Hüsker Dü’s cover of “Eight Miles High” was recorded as a warm-up for sessions that would become their groundbreaking double LP Zen Arcade, and was released as a single in April 1984, not long before Zen Arcade itself. Coming from a band that had built its reputation in the early 80’s hardcore scene—and indeed early on they played harder and faster than almost anyone—“Eight Miles High” was understood by many as a sarcastic condemnation of the classic rock establishment, and of the naïve “peace and love” vibe of the 60s counterculture. It was “Hüsker Dü’s assault on a sacred hippy hymn.”

Music historian Michael Azerrad, however, argues the track was always meant in part as an homage, and is in fact “a key to their code.” For me, as well, their cover was never about disdain, but affinity. Here’s a fusion of seemingly antithetical genres (Indian-raga/Coltrane and Anglo-American folk rock)—that becomes a model for the fusion of hardcore and folk-inspired psychedelic rock Hüsker Dü was in the process of inventing. Here’s a poetic narrative about disillusionment whose lyrics could easily have fit in on their October 1983 Metal Circus EP. Run all that through a blistering performance of supercharged psychedelic mayhem that ups the ante on anything they’d yet recorded, and it’s a template, in other words, for the kinds of songs, performances, and production that would become Zen Arcade, a brilliant album that signaled the maturation of the sound and style they’d been working towards since their inception in 1979. In many ways, it’s a declaration of musical freedom.

*

Importantly, though, their cover is not an attempt to simply reproduce the original with a more modern sound—as so many covers do. In fact, the reason their cover matters, and why it’s worth thinking about, is their ability to convey the value and meaning of the original while also pushing beyond the template that is the Byrds’ recording.

The Byrds, opening with the hypnotic combo of Hillman’s bass riff and David Crosby’s rhythm guitar, which buoys and anchors McGuinn’s ringing guitar line, provide right from the start a solid foundation for the listener’s upcoming journey. Taking a totally different approach, Hüsker’s version excises the bass (and the feeling of stability it engenders) from the opening altogether. In its place, alone, is Mould’s blistering guitar, joined soon after by Grant Hart beating out an urgent double-time roll on the kick drum and floor tom, all at a tempo that would have sunk the Byrds. If The Byrds are cruising (albeit anxiously) toward an unknown future, Hüsker Dü opens already on the edge of panic, engines pushed to their limits, nearly out-of-control.

For the Byrds, then, the entrance of the vocals creates a soothing effect. McGuinn’s guitar line, which in the short intro has become jagged and rushed, increasing in tension, suddenly drops out as the tight (and mellow) three- or four-part vocal harmony comes in. The guitar lays back into a more conventional chord progression supporting the vocals, climbing from an open E minor chord up through F# and into the clear skies of an open G and then open D. The effect of the group harmonies and ascending melody is a release from the turbulence of the opening section, an effect further supported by the group’s vocal harmonies, which suggest the mutual support of tight-knit compatriots.

In contrast, Hüsker Dü offers no such release. The vocal harmonies that dominate the Byrds’ version are replaced here by Mould’s resigned shout, which rises in intensity by the end of the first verse into a throat shredding roar. And, where the Byrds melody climbs along with the chord progression in the first line, Mould’s vocal rises and then drops. There are no clear skies to be found here, only turbulence.

Where The Byrds then move through cycles of tension and release until the song plays out with a kind of newfound confidence, the Hüsker version offers only increasing tension as the song progresses, reaching by the end a kind of desperation. When they start the third verse (which ends the Byrds’ original, but not Hüsker’s cover), Mould is already screaming incomprehensibly, his vocal transforming by the final line into a howl of desperation so intense it breaks the Byrds’ original structure—rather than moving straight to the instrumental break like the Byrds, Hüsker Dü stays on the verse pattern until the singer, and his howling, is seemingly spent. Only then do they move on.

After the third verse the Byrds return to the opening instrumental improv, but as an outro, pushing forward at a steady tempo through to the end. We therefore seem to end where we started, in the turbulent clouds of anxiety and possibility, as if what we’ve experienced by way of the verses has been a dream or vision, like the world visited by the Ghost of Christmas Future. Yet, the instrumental outro—though nearly identical to the intro—feels different here at the end, more confident than anxious. Perhaps to suggest that, despite the turbulent ride and nightmare visions, or maybe because of them, the vehicle of the song is now stronger than ever, as is the band. Moving forward into the void, they (and their listeners) are united, prepared for whatever may lay ahead.

Hüsker Dü ends the song very differently. The guitar improv through the instrumental section (the outro in the Byrds’ original) is intense as ever. And, instead of ending there, Hüsker Dü dives in for another pass at the first verse. Mould’s vocal begins the verse a desperate cry, and becomes so inconsolable by the end, all rage and howling despair, that the band is again unable to break off from the verse until the singer is spent (very haunting and intense, this goes on for a while), at which point the band finally slows and the song rolls to a stop, guitar ringing, Mould slashing at the final chords. Rather than leave us in the clouds of possibility, mid-flight, as did the Byrds, Hüsker Dü has dragged us forward into the world of the verse, the alienated future come to pass, and left us there.

For those familiar only with the Byrds’ original and its mix of foreboding and determination, and its chiming guitar and gentle harmonies, we are indeed in unfamiliar territory here. If the Byrds in 1966 meant their song perhaps as a warning, for Hüsker Dü, it has become an alarm. The future the Byrds warned us about is here, now. The trouble is not ahead. The trouble is all around us. It has put us to sleep, and we had better wake up before it’s too late.

In November 1983, Hüsker Dü revived and transformed a once great song, which over the years had become (thanks to radio stations like WEBN) another cultural sedative—something to pass the time between commercials on your commute, or to enhance your mood while shopping at The Gap—into a searing alarm, which is also an urgent plea, and a question, screaming: “Do You Remember?!” A performance so fierce, so harsh and beautiful and frantic and compelling, so unforgiving, that it still cannot be recuperated by the hypnotized world they rescued it from. And, more importantly, it cannot be ignored.

*

So, whatever happened to those Thursday nights at McLevy’s Pub with Marc, those trips up and back Route 27? The thing is, I don’t remember. In my memory they just fade away to static, like a radio signal as you’re leaving your hometown behind.

Thinking back on it now, though, what I realize is that my brother never much liked these gigs. Sure, sometimes he’d get a compliment and genuine applause, but more often than not people would ignore him. And through the years of bar smoke and shadows, I can now finally recognize the disappointment and dread that hid behind the confident mask he wore on stage, watching as these songs he’d grown up with and had spent years learning to play, and that I think he genuinely loved, were transformed through the apparatus of these performances into something alien, their vitality diminished a little more with each week, each set, each disinterested drinker, until there was nothing left but static and ash. And knowing he had unwittingly become part of the machine making that happen. This was no way to honor the past.

So, in the end, the drinkers, the world, they got what they wanted, I guess. Because at some point, the grey autumn turning to winter, the fifty bucks a week not enough anymore to make the time and effort and indifference worthwhile, my brother was finished, and so was our weekly ritual.

It’s okay, though. True, he’d do gigs like this on and off for a few years, but ultimately Marc ended up playing in a great band, got to tour, got to play at CMJ in New York, and eventually got to quit on his own terms when it was it time. And, I got something I needed, too, though it took a long many years before I really understood it. Because I got Hüsker Dü. I got “Eight Miles High.” I got my wake-up call.

Me with my first punk band, The Johnny Depps, at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, 1989. I'm the third in line--the guy wearing sandals. Missing from the photo is our singer, Thomas. Sorry, Thomas.

Jeff Sirkin grew up in Cincinnati, Ohio, and he went to college at Miami U., just like his older brother. In the late 80s and 90s, he played in a number of punk rock bands you’ve never heard of, including Las Luchadoras, Cap’n Courage, and the Johnny Depps. More recently, he is the author of the poetry collection Travelers Aid Society (Veliz Books) and the micro-chapbook Summer Break (Rinky Dink Press), as well as co-editor of the online poetry journal A DOZEN NOTHING. He lives in El Paso with his partner and their twelve-year-old daughter.