(8) chuck berry, “my ding-a-ling”

donged

(4) MILLI VANILLI, “DON’T FORGET MY NUMBER”

274-254

and will play in the elite 8

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on March 20.

those of you who will not sing: martin seay on “my ding-a-ling”

“My Ding-a-Ling” was Chuck Berry’s only number-one hit.

I’m going to say that again. “My Ding-a-Ling” was the only song Chuck Berry ever recorded that hit number one on the Billboard pop charts.

Chuck Berry, y’all.

Like a confident litigator who calls no witnesses and simply states that the correct verdict is self-evident from the facts at hand, I am tempted to end my March Badness essay right here. By any metric you can think of—misguided conception, half-assed execution, unworthiness of its performer, unmerited popularity relative to the rest of the artist’s oeuvre, the sweeping systemic out-of-jointness that its success represents—“My Ding-a-Ling” is obviously the worst song in the modern history of popular music. And it ain’t close.

But bad things have much to teach us about where value resides, though their lessons can be painful. To that end, let’s spend a moment with each of the three major elements of the catastrophe:

“My Ding-a-Ling” was

Chuck Berry’s

only number-one hit.

1

In each of its recorded iterations, “My Ding-a-Ling” is a song about having a penis.

The version we’re most directly concerned with is the one issued as a single by Chess Records in July of 1972, the one that held the top spot on the Billboard Hot 100 for two weeks in October of that year, thereby qualifying for the present contest while causing a couple of vastly superior songs—“Use Me” by Bill Withers and “Burning Love” by Elvis Presley—to peak at number two. In a narrow technical sense this is the best “Ding-a-Ling” on record, in that it announces its aims most clearly and achieves them most successfully. (But should we at this point consider whether we ought to call it the best when those aims are deleterious? When a song is fundamentally bad, shouldn’t we want it to be less effective? Wouldn’t it be better if it were worse?)

The first important thing to note about “My Ding-a-Ling” is that many people are to blame. Sleeve notes always credit Berry as the song’s only author, which he definitely was not; the original was written by Dave Bartholomew, a legendary New Orleans bandleader, producer, and arranger who—along with a small, scattered coterie of collaborators and rivals—determined in the years following World War Two what the next half-century of popular music was about to sound like. (In addition to being an architect of what became known as the New Orleans sound, Bartholomew wrote or co-wrote classics like “I’m Walkin’,” “Blue Monday,” “I Hear You Knocking,” and “Ain’t That a Shame”; suffice to say that “My Ding-a-Ling” is not among his best work.) In 1952 Bartholomew and his band recorded it for both the Imperial and King labels, under two different titles; a couple of years later, Imperial released a new version—now called “Toy Bell,” still crediting Bartholomew as the composer—by the Bees, a group mostly remembered for launching the solo career of singer Billy Bland.

Bartholomew’s own renditions of the song are just straightforwardly dumb. In them the eponymous ding-a-ling is a euphemism more than a double entendre: very little attempt is made to suggest non-penile connotations. The Bees—maybe hoping to attract a larger, more respectable audience by imparting some semi-plausible deniability—were the first to introduce the ironic frame that defines Berry’s hit: the opening declaration that the ding-a-ling is literally a toy bell, and not, y’know, whatever you filthy people might be thinking. This move allows the singer to address a double audience by adopting a childlike faux-naïf persona that matches the baby-talk register of the title phrase, a persona that’s further bolstered by the addition of a new verse set in Sunday school and by the rearrangement of Bartholomew’s original verses into roughly auxological/gerontological order, concluding as follows:

When you’re young and on the go

Your ding-a-ling won’t ever get sore.

When you are old and you’ve lost your sting

You won’t need the doggone thing.

None of these records charted. Like an unexploded mustard-gas shell deep beneath a Flemish field, “My Ding-a-Ling” lurked in sinister obscurity for years. And then Chuck Berry came along.

It’s hard to pinpoint exactly when this happened. In his deeply strange, often creepy, occasionally amazing 1987 autobiography, Berry writes that he “had been singing it for four years prior” to its ascendancy as a hit single; this curiously specific timeframe is probably an oblique reference to “My Tambourine,” his first documented crack at adapting it, which appears on his 1968 album From St. Louie to Frisco. Although Berry began his recording career on the scrappy independent Chess, and to Chess he’d soon return, “My Tambourine” dates from his lackluster three-year stint on the much larger Mercury; one suspects that Mercury and its attorneys were somewhat less shrug-emoji about intellectual property rights than Chess was, because there’s quite a bit of daylight between Berry’s “Tambourine” and his “Ding-a-Ling”: the central metaphor, obviously, is different, and so is the melody. The end product circumvented legal jeopardy mostly just by sucking in an uncommitted way, and thus not attracting much attention. The copious reverb, probably slathered on to make Berry seem relevant to kids accustomed to heavier rock, doesn’t suit the song; meanwhile, the mambo-inflected rhythm is at least a decade out of fashion, and Berry’s hipster phraseology—“she dug my music and my routine”—seems forced. By 1968 even the tambourine itself had largely passed its moment as a hippie signifier.

Also, the tambourine metaphor just doesn’t work. Penises, while roundish, are not generally wider than they are long; nor, absent certain modifications, do they jingle. More to the point, “tambourine” wasn’t an established code word for much of anything, whereas most speakers of American English would have understood Bartholomew’s anatomical referent immediately. While the entry for “ding-a-ling” in the Oxford English Dictionary does not indicate its usage in print to mean “penis” prior to 1972, this is one of those areas where print lags common parlance. “Tinkle,” somewhat relatedly, was in place prior to the midcentury as an onomatopoetic euphemism for urination; from there, the resemblance of a flaccid penis to the swinging clapper of a bell is a pretty easy leap. “My Tambourine” advantages itself of none of this, and without nailing the anatomical metaphor, the song never comes together. The last verse, in which the tambourine is “linked up” to a tenuously vaginal graduation ring, is a complete conceptual disaster.

But in this version we do find two elements that show a path forward. The first is the rhyme of “grammar school” with “vestibule,” which is actually really good, a move that only a few other pre-hip-hop lyricists of note—Lorenz Hart, Cole Porter, Bob Dylan, maybe Willie Nelson—could have come up with, and that any of them might have admired. The second is Berry’s adjustment of the original lyrics to amplify themes of preadolescent sexuality and to remove references to senescent impotence, topics that are respectively extremely on- and extremely off-brand for him. “My Tambourine” was a misfire, a venting of steam that hinted at the churn of as-yet-unseen magma; “My Ding-a-Ling” was not done with Chuck Berry, nor he with it.

Flash forward to February 1972, the Lanchester Arts Festival, the Locarno Ballroom in Coventry, England. Early in his career—mostly to maximize revenues, and probably on some level to minimize his personal and professional entanglements—Berry had adopted the unusual practice of touring without a band: he’d tell each promoter to provide him with a Fender Twin Reverb amplifier and a competent local group, he’d show up with his guitar minutes before showtime, and the concert would begin, with no rehearsal, not even a setlist. (Early in his career Bruce Springsteen was in one of these local bands; in a 1987 concert documentary he recalled the extent of the guidance he got from Berry: “I said, ‘What songs are we going to do?’” “And he said, ‘Well, we’re going to do some Chuck Berry songs.’ That’s all he said.”) If the musicians were shaky, the shows could be awful; if they had good ears and were fast on their feet, they could be great. The show in Coventry went pretty well. Chess had had it recorded—allegedly without Berry’s knowledge—and used much of it as the second side of The London Chuck Berry Sessions, an LP released later that year.

These unrehearsed gigs also went better when the audience was enthusiastic, and by all accounts the crowd in the Locarno Ballroom was nuts. Berry was known for playing short sets and doing no encores; he didn’t encore in Coventry, but he did extend his set, feeding off the room’s energy, and this created consternation for the festival organizers. By the time he finished up with a blazing “Johnny B. Goode” he’d run over his allotted time by fifteen minutes; the Sessions LP ends with the crowd chanting We want Chuck! as the emcee pleads with them to settle down so Pink Floyd can take the stage. If you listen closely enough you just might be able to hear the spark of UK punk in that moment.

Anyway, the main reason why Berry ran over his allotted time is that when the emcee signaled him to come off, he instead turned back to the crowd and played “My Ding-a-Ling.”

For eleven and a half minutes.

Seriously. Berry’s original recorded version of “My Ding-a-Ling”—under that title, at least—is ten seconds longer than “Sad Eyed Lady of the Lowlands.” Now, to be fair, most of that runtime consists of Berry’s instructions to the audience and his salacious patter between verses. Then again, to be fair, salacious patter between verses is a huge part of what his “Ding-a-Ling” is all about.

If the folks at Chess knew they had a hit on their hands, there’s no real evidence of it. As Bruce Pegg recounts in his unauthorized Berry biography Brown Eyed Handsome Man, the trip to England didn’t yield as much usable material as the label had hoped: Berry’s microphone blew midway through the Coventry show, rendering most of the audio unusable. (Half of The London Chuck Berry Sessions consists of hastily-scheduled studio recordings that turned out surprisingly well, thanks in large part to the recruitment of three excellent players: keyboardist Ian McLagan and drummer Kenney Jones of the Faces, and bassist Ric Grech of Blind Faith and Traffic.) Had that mic not blown, it’s not clear that “My Ding-a-Ling” would have made the cut.

As the story goes, after the LP came out, Chess began to hear from a few radio deejays—all apparently unconcerned about their job security—who’d been playing “My Ding-a-Ling” on the air in its entirety, to an overwhelming response. In the early days, the Chess brothers had run their business with the understanding that every hit song is on some level a novelty song, and a certain measure of that spirit still remained in 1972; the label decided to take a scalpel to the full-length “Ding-a-Ling” with the hope of locating a coherent single therein. This daunting task fell to legendary producer Esmond Edwards—then Chess’s vice president for artists and repertoire, one of the industry’s first African-American executives—who had previously worked on recordings by Eric Dolphy, Coleman Hawkins, and John Coltrane, among many others, and one can’t help but wonder whether he paused at his console for a moment to ponder the series of events that had brought him to this odd episode in his distinguished career. Edwards’s efforts yielded the four-minute, eighteen-second edit that Chess released in July of ’72, and that’s the one that worked its way inexorably, virulently up the Billboard charts.

A number of technical factors made “My Ding-a-Ling” a hit after “My Tambourine” wasn’t. The first, of course, is the restoration of Bartholomew’s original metaphor. The second, I think, is the freedom that the restored metaphor provided Berry to imaginatively inhabit the song. While Bartholomew’s and the Bells’ renditions are wry, cool, and a little philosophical—describing events in an indefinite past tense, making general observations about sexual potency and the waning thereof—Berry deploys his prodigious storytelling skills to sketch vivid, inventive, particular scenes that emphasize the corporeality of the ding-a-ling, presenting it not as a sexy metonym but as an organ: susceptible to injury, a site of compulsive pleasure. In Edwards’s edit this focus is even sharper, shorn of content that’s slack or redundant. (Edwards had the wisdom, for instance, to cut the Sunday school / Golden Rule verse that Berry had lifted from the Bees’ version, while retaining Berry’s own similar but superior grammar school / vestibule addition.) The pared-down material that remains, while not good, per se, will for damn sure hold your attention: it’s agitated, aroused, and anxious, live in more than one sense.

And that’s the biggest reason why Berry’s “Ding-a-Ling” hit: the fact that it was recorded live. The song’s humor, such as it is, requires an impression of spontaneity that’s antithetical to a studio recording. It also benefits from the presence of an audience, by way of the deeply-rooted human tendency to laugh when other people are laughing, a phenomenon to which innumerable mediocre improv troupes owe their subsistence.

Do we buy Berry’s assertion that he didn’t play “My Ding-a-Ling” live prior to 1968? We do not. Berry performs it like something he’s lived with, thought about, and road-tested for years. His rap with the audience—which is no less rehearsed than the song itself, as the multiple performances available on YouTube that I watched so you don’t have to (you’re welcome) clearly attest—has the feel of material that he developed in the early Fifties, in the little East St. Louis clubs where he got his start. By 1972 this is a song that he knows, that he’s been adding to, subtracting from, tweaking based on crowd responses, and generally making his own to such a great extent that he might have sincerely forgotten that he’d copped it from somebody else.

And, so, yeah, okay, a word about that.

2

“Leonard Chess had explained,” Berry writes, describing his preparations for his first professional recording session,

that it would be better for me if I had original songs. I was very glad to hear this because I had created many extra verses for other people’s songs and I was eager to do an entire creation of my own.

Berry’s autobiography abounds with statements like this. What seem at first like careless bits of self-incrimination are in fact rhetorical moves, gentle suggestions that those who’d accuse him of misbehavior might be using the wrong rulebook. From the outset Berry understood—quite correctly, and probably better than people on the business side of pop music cared to admit—that the distinction between original and borrowed material is not binary. For all his considerable sophistication, Berry thought of himself as participating in a folk tradition, one that includes blues and country and Cajun and calypso and every other music played by and for the working class, in fields and freight-yards and factories, brothels and barrooms and barrelhouses, a tradition that derives much of its vibrancy from being in unrestricted conversation with itself. He didn’t seem to acknowledge a huge difference between inventing something entirely new and just doing something somebody else came up with better than they had done it.

But this formulation gets a bit sticky in the extremely frequent instances when the artist who does the borrowing is doing it from a position of elevated privilege, particularly when that privilege is white. Berry and/or his record labels may have neglected a few footnotes over the course of his career, but he unquestionably gave more than he took, having been ripped off—reverently or cynically, directly or indirectly, with credit or without—six ways from Sunday by a large percentage of literally everybody who picked up a guitar at some point during the past 65 years.

Not all of Berry’s debtors were white, but the most successful certainly were. The story of the dawn of rock ’n’ roll is often told, but worth reviewing: starting in about 1955, the cohort of artists who were achieving commercial success by adapting jump blues into something distinctly modern was multiracial, with Berry, Little Richard, and Fats Domino keeping pace with Bill Haley, Elvis Presley, and Jerry Lee Lewis. Berry’s breakthrough single “Maybellene” was in fact the first pop hit by an African-American to outsell the cover versions of it released by white artists, an achievement that for a glittering moment suggested that interracial exchanges legally prohibited throughout much of the United States might yet be accomplished, in some small but significant way, through commerce in popular music. But as the days passed, white rock ’n’ rollers continued to emerge and prosper, while black rock ’n’ rollers generally did not, and within three or so years it was all pretty much over, with Elvis in the Army, Lewis in disgrace, Little Richard back in church, Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens, and the Big Bopper dead in a plane crash, and Berry… well, we’ll get to that in a minute. Fare such as “Stupid Cupid,” “The Battle of New Orleans,” and “The Purple People Eater” took over the charts, and for a time pop music went to shit again.

The significance of those rock ’n’ roll pioneers didn’t really become evident until the following decade, and even then you had to know what to listen for. The up-and-coming rock artists who repurposed this early material were generally honest, or at least frank, about citing their sources—to do so was proof of connoisseurship—but for the most part the audiences didn’t care, and without getting demand letters from attorneys the music industry wasn’t cutting anybody any checks. Of the first-generation rock ’n’ roll innovators, no one was plundered more extensively or blatantly than Berry. I’m not talking about Pat Boone covers here, or any other unambiguously cringey instances of whitewashing; we’re after bigger fish. Berry collected legal settlements from both the Beach Boys, whose “Surfin’ U.S.A.” uses the melody of “Sweet Little Sixteen” without attribution, and the Beatles, whose “Come Together” draws music and some lyrics from “You Can’t Catch Me.” While it’s not close enough to land anybody in court, the similarity of Bob Dylan’s “Subterranean Homesick Blues” to the comparably motormouthed “Too Much Monkey Business” is also pretty hard to miss.

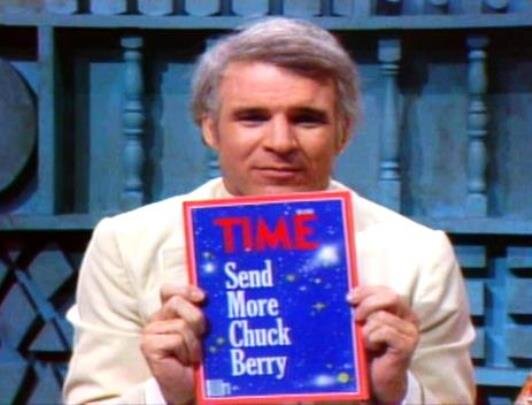

As you may have noticed, I just named what are arguably the three most iconic white acts of the 1960s—the ones most often credited with Changing Music Forever—which leads me to a point that has gone unstated too long in this essay: Chuck Berry was a goddamn genius, securely numbered among the most consequential figures in the history of global popular culture. This cannot be overstated, and is not in dispute. In the concert documentary mentioned parenthetically above, Eric Clapton explains how “If you were going to play rock ’n’ roll, or any upbeat number, and you wanted to take a guitar ride, then you would end up playing like Chuck, or what you learnt from Chuck.” In 1961, on a train platform in Kent, a young man struck up a conversation with another whom he’d spotted carrying a copy of a Berry LP that was hard to get in the UK; the men’s names were respectively Keith Richards and Mick Jagger. In 1976, when Ann Druyan and Carl Sagan were putting together musical selections for the golden record placed aboard the Voyager deep-space probes—a record designed to communicate the essence of humankind to any extraterrestrial beings who might one day encounter it—the only rock song they chose to include was Berry’s “Johnny B. Goode.” Steve Martin joked about it on Saturday Night Live, predicting the first message that Earth will receive from beyond our solar system:

Chuck Berry was a goddamn genius. Were this not the case, the sordid stupidity of “My Ding-a-Ling” wouldn’t be worth complaining about.

We should, however, try to be specific about of what exactly his genius consists. Strictly speaking there’s no aspect of Berry’s craft that hadn’t been done before; his most-often-cited innovations—onstage showmanship, overdriven electric guitar, two-string leads, pushing the rolling boogie-woogie of jump blues toward the more urgent two-four of Western swing—could all be plausibly claimed by predecessors and contemporaries, from Ike Turner to Bill Haley to Louis Jordan to Sister Rosetta Tharpe. Berry’s contribution lay in putting the pieces together better than anybody else, and demonstrating the breadth of what the new form could accomplish.

“Maybellene,” the aforementioned breakthrough single, qualifies as a major compositional achievement even though it takes its rhythm and most of its melody from the Western swing tune “Ida Red.” In addition to his fast, noisy, not-quite-under-control guitar work, Berry supplies a new chorus and verses that establish him right out of the gate as one of the two most innovative lyricists of the 1950s. (The other one, Willie Dixon, happens to be the bassist on the recording.) Berry’s words glide along on the familiar melody, rushing with the music, dancing alliteratively among varying vowels, setting scenes and evoking action in a manner that any novelist might well envy. What’s particularly striking is his confidence, which may be the most rock-’n’-roll aspect of the performance: when he can’t find the right language to make a line work, he just coins his own and keeps going. “As I was motorvatin’ over the hill,” he sings; “motorvating” isn’t a real word, doesn’t mean anything, except suddenly it is and does: not only a word, but the perfect word.

Most importantly, Berry understood that true verbal mastery must always take account of the audience it addresses, and what that audience wants. In one form or another, “Ida Red” probably goes back to the Civil War; it had certainly been widely known for more than a decade when Berry first started playing it and similar material in the clubs where his career began. As he writes,

The music played around St. Louis was country-western, which was usually called hillbilly music, and swing. Curiosity provoked me to lay a lot of the country stuff on our predominantly black audience and some of the clubgoers started whispering, “Who is that black hillbilly at the Cosmo?” After they laughed at me a few times, they began requesting the hillbilly stuff and trying to dance to it. If you ever want to see something that is far out, watch a crowd of colored folk, half high, wholeheartedly doing the hoedown barefooted.

Throughout his career Berry maintained an impressive unwillingness to stay in his lane. Whenever he encountered a pop genre or trend that seemed fun, interesting, or potentially lucrative—not just country, but blues, ballads, calypso, even Latin- and Italian-themed songs that were briefly in vogue—he’d take a swing at it, and an important aspect of his overall bequest to his successors is the modeling of this catholicity. He helped establish rock music as both a potent solvent of social and ethnic barriers and, not coincidentally, as the soundtrack of recuperative capitalism.

Of all the fence-hopping Berry did, the first instance remains the most notable: his discovery that African-American audiences—despite, or more likely because of, the towering legal and practical barriers that kept them separate from it—were utterly fascinated by the culture of their white working-class counterparts. That discovery made Berry a big draw in his native St. Louis, but it also hipped him to the flip side of that phenomenon: the fact that the fascination was no less intense in the other direction.

This was a realization that he needed the help of others to exploit. Here we should note that despite all the mythology surrounding its heroes, rock ’n’ roll was almost entirely the result of economic and demographic factors—i.e. the post-Depression baby boomlet hitting puberty, with the postwar baby boom close on its heels—as well as the rise of technologies that expanded these kids’ capacity to make consumer choices independently of their parents and other authorities: affordable cars, good highways to drive them on, portable transistor radios, and high-powered radio stations. The most important single figure in rock ’n’ roll isn’t a musician at all, but rather deejay Alan Freed, who popularized the term and helped define the sound by playing the records of both black and white acts in huge broadcast markets. (Freed is in fact credited as a writer on “Maybellene,” to which he contributed neither a word nor a note; the credit was a way for Chess to funnel him royalties in exchange for spinning its records, one of the shady practices that would end Freed’s brief career when the payola scandal broke in ’59.)

Musicians, of course, had been listening to each other across racial lines since forever, but these postwar technological advances made it possible for audiences, principally teenage audiences, to effortlessly traverse such lines without leaving the privacy of their homes and vehicles. A big part of Berry’s genius is the fact that he saw this shift coming, and understood what it meant. It’s noteworthy that many of his early songs—“Roll Over Beethoven,” “Rock and Roll Music,” “Johnny B. Goode”—more or less announce themselves as cultural forces: they tell you what they’re doing even as they’re doing it.

Berry’s canny analysis of his young audience’s unspoken desires certainly helps explain why, starting in 1957 and continuing for several years thereafter, he wrote and recorded a series of singles that featured teenage protagonists, often set in schools. While never overtly unwholesome, songs like “School Day,” “Sweet Little Sixteen,” “Almost Grown,” and “Little Queenie” were unmistakably intended to seduce teenagers, to affirm and encourage their agency, especially their sexual agency. This begins to seem a little creepy when we consider that Chuck Berry was thirty years old in 1957. Add a little more biographical context, and it begins to seem a lot creepy.

Because here’s the thing: in addition to being a genius, Chuck Berry was also, by many credible accounts, quite an asshole. This is a point that can be easily overstated, because the most-often-cited complaints against him—that he was rude, stingy, cold, mercenary, embittered, distrustful, deceitful, ungrateful, prone to engaging in head games and power trips at the expense of effective performances, and generally just shitty to deal with—can be largely explained, if maybe not entirely excused, by the shoddy and exploitative treatment he got from every corner of the music industry throughout his career, treatment that was often explicitly and just about always implicitly racist.

Some complaints about his conduct, however, are harder to dismiss. Though the consequences were worse than they would have been for a white musician in comparable circumstances, much of Berry’s trouble was at least somewhat earned, and of his own making.

In the early 1940s, if you had asked any resident of the Ville, a prosperous African-American neighborhood in St. Louis, to predict which of Henry and Martha Berry’s six children would go on to have a successful career in music, that resident a) would have known who you were talking about, and b) would definitely have answered Lucy, the third of the six, who was an accomplished mezzo-soprano and a skilled pianist who’d benefitted from an excellent music education at Sumner High School. The Berrys were a bourgeois family in a bourgeois neighborhood: Henry was an independent home-repair contractor and a Baptist deacon, and Martha was a well-read schoolteacher; she named her youngest son after the poet Paul Laurence Dunbar. The fourth child—Charles, later called Chuck—was known less as a musician than as a charismatic fuckup; he did give a memorable performance of a blues song at a school talent show once, but it was remembered less for its quality than for scandalizing the Sumner faculty, who maintained that such music was beneath the dignity of its pupils. Berry didn’t like school, and got held back a couple of grades, but he was still officially enrolled in 1944, when he and some friends committed and were arrested for a series of armed robberies and the theft of a vehicle. He received a ten-year sentence for the offenses, of which he served three.

This was not to be his last stint in prison. In 1960, just off the height of his fame, Berry was indicted under the Mann Act for transporting women across state lines for “immoral purposes” in two separate incidents, respectively involving a white girl between sixteen and eighteen years old and a fourteen-year-old Apache girl. (It’s safe to assume that Berry wasn’t the only well-known musician having sex with teenagers, and therefore also safe to assume that race had some bearing on the prosecutor’s decision to charge.) Although acquitted in the first case—the young woman testified that she was in love with Berry, which the jury apparently accepted as evidence that the couple’s intent wasn’t immoral enough to be illegal—he was convicted in the second, and sentenced to five years. Berry’s attorney appealed based on energetically racist statements made by the judge; the Eighth Circuit agreed, and ordered a new trial, at which Berry was convicted again. This time the sentence was three years, of which he served twenty months at the federal lockup in Terre Haute, Indiana, beginning in early 1962.

As was noted in court and widely reported at the time of his sentencing, Berry was a thirty-three-year-old married man with three young daughters at home, and one imagines some concern around the Chess offices over whether his fans would desert him, just as many of Jerry Lee Lewis’s fans had jumped ship following the revelation that he had married his thirteen-year-old cousin. These concerns turned out to be largely unfounded: Berry started recording singles again immediately after his parole, and some of them—including “No Particular Place to Go,” a humorous song about driving a woman around in an automobile with carnal intent, released four years after Berry was convicted of driving a woman around in an automobile with carnal intent—charted impressively, which suggests either that public mores had suddenly changed, or that Berry’s fans had already priced in his misbehavior, that it might even be part of his appeal.

In 1979 Berry pleaded guilty to evading federal income taxes and did four months in the federal correctional institution in Lompoc, California, a period that he seems to have almost enjoyed; according to his autobiography he treated it more or less like a writer’s residency, taking a typing class during which he banged out much of that very book. It was to be his last sojourn behind bars, though not his last brush with the law. In 1987, under circumstances that remain unclear, he hit a woman in the face at a hotel in Manhattan and drew an arrest warrant for assault; he eventually pleaded guilty to a lesser charge and paid a fine to resolve the incident.

That’s not all. In his later years, Berry concentrated on various real estate and other business ventures, one of which was the Southern Air restaurant in Wentzville, Missouri, a St. Louis suburb where he had long maintained a sprawling compound. Berry’s first encounter with the Southern Air was a meal that he and his ne’er-do-well friends ate there in the days immediately prior to the crime spree that first landed him in prison; the restaurant was whites-only then, and they were served through a side window. His return years later to buy the place would have been a good basis for a heartwarming narrative of triumph but for subsequent events. In 1989 Berry was the target of a class-action lawsuit by group of women alleging that they had been videotaped without their knowledge or consent while using the restroom at the Southern Air; the prosecuting attorney of St. Charles County was also gearing up to charge Berry with multiple felonies—including child abuse, based on the fact that children had been among those videotaped—and probably would have done so had he not been defeated in his reelection bid. In Brown Eyed Handsome Man, Bruce Pegg argues persuasively that the nationally-publicized Southern Air affair was driven by the animosity and greed of a couple of disgruntled employees, the prosecutor’s political aspirations, and the longstanding racist hatred that many residents of St. Charles County felt toward Berry. What Pegg cannot dispute, and all but confirms, is that Berry had indeed been shooting voyeuristic videos of the women’s restroom. Eventually he paid out a settlement, and the issue slowly went away. Berry remained in Wentzville and continued to play regular gigs until 2017, when he died at the age of ninety.

What’s most disturbing about Berry is the inescapable suggestion that these two major traits—virtuosic pied piper of America’s youth, and sexually compulsive predator—cannot be disentangled: that his genius cannot be easily extricated from his bad behavior, that the latter infests the former to its core. Part of the dangerous, faintly illicit thrill of Berry’s best music comes from the impression of these tendencies circling each other, sparks arcing through the gap between them, achieving an unstable equilibrium.

And part of what makes “My Ding-a-Ling” so awful comes from the impression of this equilibrium collapsing, just utterly showing its ass.

3

Near the end of his autobiography, Berry advances a rather peculiarly-worded vision of a future “when all races and nationalities in the United States will be merged”:

Now, wouldn’t that be real nice? A one-race, normal-face, average-shade, medium-made, balanced-weight, open-fate society with no disturbing variants. […] But there’s no way people would be content with such monotony. It just wouldn’t work.

Read in 2020, that sounds painfully like the sort of optimistic, daydreamy prediction that one might remember hearing expressed circa 2009; I suspect it fell similarly upon the ear when it was published in 1987, evoking a strain of facile, fatuous hippiedom that hadn’t aged particularly well.

What strikes me as interesting is, first, that it’s an unusual idea to see expressed by an African-American musician, given the history of such sentiments being used opportunistically by white people to avoid confronting persistent injustice and unacknowledged injury; black music post-James-Brown has tended to emphasize dignity and visibility, rather than aspiring toward some post-racial amalgamation. Berry’s rise to fame, of course, had been closely associated with exactly this sort of ethnic boundary-blurring, but it manifested in other aspects of his life, too; Pegg, for instance, documents the light-skinned Berry’s early efforts to pass himself off as American Indian or Polynesian, and Berry himself writes with amusement about his use of photographic tricks to appear white in publicity photos. When he wrote “Johnny B. Goode,” Berry reports, he decided to make Johnny hail from Louisiana because New Orleans was “where most Africans were sorted through and sold”—but he also changed the original lyric from “colored boy” to “country boy,” so as not to “seem biased to white fans.” This move—simultaneously evoking and evading the topic of race—is extremely Chuck Berry.

The second (and more) interesting thing about this post-racial vision is the degree to which it’s specifically bodily, and implicitly libidinal. The merging that it posits is presented as purely genetic, not social or cultural, and population-scale genetic merging requires a bunch of promiscuous, procreative sexual intercourse. I mean, it just does. This tendency to understand society in principally libidinal terms is also reflected in the summary of Berry’s heritage that appears in one of his early chapters; it emphasizes his mixed African, Anglo, and indigenous American ancestry, and reads like a softcore adaptation of Genesis 5: genealogy as erotica.

If we step back and look at Berry’s life as a whole—his crossing of racial lines in both music and sex, his disregard for the age of consent, his wantonness throughout his seventy years of marriage, his unapologetic criminality, his refusal of professionalism as a live performer, even his casualness about copyright—a pattern emerges, which is the willful obliteration of distinctions and limits. Given that bourgeois values are chiefly defined by the strict maintenance of distinctions, I would argue that Berry is probably best understood as an anti-bourgeois artist.

Bourgeois values are stuffy as hell, I get that. Berry smashed a lot of extremely tacky shit during his cartwheels through America’s china closet, shit that needed smashing. But the problem with obliterating bourgeois strictures willy-nilly is that a more equitable means of organizing society doesn’t automatically materialize to take their place; in practice, what emerges often ain’t pretty, as any number of early-70s Laurel Canyon songwriters observed. When we cease to regard one another sentimentally, we usually end up regarding one another instrumentally instead, much as Berry seems to have regarded fellow musicians, concert promoters, and the young women with whom he had sex. Viewed from this standpoint, our very personhood recedes, becoming fictional, false.

I don’t think it’s too much of a stretch to suggest that Berry’s attitudes were first manifested, and may have originated, in the dynamics of the prosperous household where he grew up: the strict religious parents, the large group of siblings, the praise and local renown accrued by a gifted older sister. Of all the telling anecdotes in Berry’s autobiography, one that describes his rivalry with that sister—years before he had the self-possession to write “Roll Over Beethoven”—strikes me as particularly revelatory:

Lucy, becoming more and more sophisticated in music at school and at home, was constantly gaining recognition for her singing accomplishments. Playing and singing her classical songs consequently gave her priority above any of us to play the piano at home […] which greatly limited by growing enthusiasm for picking out my favorite boogie-woogie numbers. I got so mad at her one day that I broke wind in one of Mother’s old fruit jars, put my hand over it, came back, and set it out on the piano in front of her to pollute her playing.

There you have it, my friends: “My Ding-a-Ling” is the jarred fart of modern popular music. Because, let’s be honest, if it were merely a bad song by one of the great geniuses of the twentieth century, it still wouldn’t be worth complaining about. (Few among us, by comparison, spend time and emotional energy bemoaning the existence of Bob Dylan’s “Wiggle Wiggle.”) What qualifies it as the absolute worst is its reach, its power, its demonstrated ability to infect and to spoil.

What’s upsetting about “My Ding-a-Ling”—Chuck Berry’s only number-one hit, you’ll recall—is the fact that it was rewarded so abundantly. Not even that, it’s the fact that it was rewarded so abundantly when it was the worst thing Berry ever recorded, while the best things Berry ever recorded are among the best things anybody ever recorded. It’s almost Lovecraftian in its perfect wrongness: an aperture to a world in which our lofty ideals and principled aspirations are parodied and defiled… or, worse, through which that world has already permeated our own.

Listen to him one more time, cooing instructions like he’s running icebreaker activities at an orgy. Berry repeatedly addresses the predominantly teenage audience as “children,” putting himself in the role of tutor, which would be risqué coming from just about any performer given the nature of the material; coming from Berry, less than a decade out from his Mann Act incarceration, it’s positively squirmy. And the kids love it. Listen to the singalong, the creeping participation, the compliant self-sorting by sex. We want Chuck! To what extent is their enthusiasm sincere, and to what extent sarcastic? Are they laughing with him? At him? Both? To what extent is Berry in on the joke? Does it matter? Those of you who will not sing / you must be playing with your own ding-a-ling! Ha ha ha! Onanism and fucking: there is nothing else.

When we hear a great song—“We’re in the Money,” “These Foolish Things,” “Over the Rainbow,” “Don’t Get Around Much Anymore,” “La Vie en rose,” “Bésame Mucho,” “Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen,” “That’s All Right,” “I’ve Got You under My Skin,” “Respect,” “I Want You Back,” “Inner City Blues,” “Águas de Março,” “Mannish Boy,” “Heroes,” “I Will Survive,” “Time After Time,” “This Charming Man,” “Raspberry Beret,” “How Will I Know,” “Check the Rhime,” “You Oughta Know,” “Single Ladies,” “Dancing on My Own,” click the links, listen to that shit, you owe it to yourself—our embodied experience of the world is enriched and expanded, and we’re freshly amazed at what human beings in our best moments can create. These songs leave us more alive, more alert to the present moment and the possibilities that spill from it.

“My Ding-a-ling” does more or less the opposite, suggesting that despite any and all pretentions to the contrary, we amount to no more than genitals schlepped around by motile meat. We not only accepted this message but sought it out, insisted that it be dumped onto our airwaves, demanded through our sheer numbers that it be packaged for individual sale, the better to throw our money at it. We split ourselves in two; we laughed and we sang. We wanted this, and chose it. It is what we are.

Martin Seay’s debut novel The Mirror Thief was published by Melville House in 2016. Originally from Texas, he lives in Chicago with his spouse, the writer Kathleen Rooney.

AMORAK HUEY ON “BABY DON’T FORGET MY NUMBER”

Of course everything about the Milli Vanilli story feels scripted.

But where do you start the movie?

Perhaps it depends on what you want the message to be, what you think the point of it is, but that’s the problem. Trying to find a message. A theme. A moral of the story, beyond “This thing happened, and it’s kind of funny, a pop culture punchline, but it’s also incredibly tragic, so we don’t want to make too much fun of it.”

No wonder they haven’t made the movie yet, despite it seeming to be a natural fit, despite the movie being long rumored, despite the fact that nearly everything written about Milli Vanilli in the past two decades mentions the possibility of a movie, the appropriateness of a movie, the inevitability of a movie.

The Milli Vanilli saga is all story and no plot, in the E.M. Forster sense of the terms: the king died and the queen died—that’s a story. The king died and then the queen died of grief—that’s a plot. The story here is simple: the duo lip-synced and the duo got caught. The plot? That’s more difficult to pin down, though there surely is plenty of grief in it.

SCENE: BRISTOL, CONNECTICUT, JULY 1989

This moment is the encapsulation of the Milli Vanilli fraud, the physical embodiment of things ripping apart at the seams, a star falling from the sky in real time. It would be a fine place to start the movie.

On stage at a Connecticut theme park, as part of the Club MTV Tour. Cameras everywhere. The red-hot pop duo Milli Vanilli, Rob Pilatus and Fabrice Morvan, a ridiculously good-looking pair rocking hair extensions and tank tops and bicycle shorts that highlight their muscular thighs and crotch bulges, play their hit song “Girl You Know It’s True.” Lights are flashing. Thousands of fans dance and scream and sing along.

Then something goes wrong with the sound system. The song catches, then sticks. The title repeats. Over and over. It’s agonizing.

“Girl you know it’s—”

“Girl you know it’s—”

“Girl you know it’s—”

“Girl you know it’s—”

They duo gamely tries to cover, but the track continues to skip. Rob gives it a few head pumps before giving up and rushing off the stage, his head down, his thigh muscles gleaming. “I wanted to die,” he says.

In case you’ve forgotten the details, here’s the deal with Milli Vanilli, the essence of the scandal: they did not sing their own songs. They weren’t merely lip-syncing this one live performance, they were always lip-syncing. The voices on their hit songs belonged to someone else. One of the biggest hoaxes in music history, and here it was, the truth coming out live on MTV. Yes, it seems scripted. Made up for the movie. But it really happened. You can watch it here:

How dramatic, right? It’s the curtain rising to reveal the man in the corner pulling the levers. It’s Shaggy and Scooby pulling the mask off the monster to reveal it’s been the museum curator all along. The dramatic ending of a scam. Only it isn’t. It’s only in hindsight that this scene takes on such weight. At the time? MTV’s Downtown Julie Brown runs after Rob and shoves him back onto the stage. Some technician fixes the sound system. And the show goes on, for another year and a half.

SCENE: WEST HOLLYWOOD, CALIFORNIA, NOVEMBER 1991

The Mondrian Hotel, overlooking Sunset Boulevard. A balcony. A railing nine floors up. The vertigo of looking down from such a height.

Rob Pilatus—who said he wanted to die back there in Bristol—strung out and desperate, thinking of climbing onto the railing. Maybe actually climbing partway onto it. Thinking of jumping. But the phone rings in the room behind him. He goes in to answer it. Deputies rush in and grab him, drive him to Cedars-Sinai for rehab and observation.

Because Milli Vanilli’s credibility is utterly shot at this point, people aren’t sure how to feel about the news of Rob’s suicidal behavior. Is it just another hoax? An attempt to win back public sympathy? That’s beside the point, though. There’s no doubt he is a desperate man, and no wonder.

The Bristol event didn’t expose Milli Vanilli to the general public, despite happening in front of thousands of fans and live on MTV. For one thing, this is before every fan in attendance has a phone to capture the moment, before social media and viral videos and instant TikTok parodies. For another thing, lots of acts lip-sync their live performances, or parts of them. But what happens on that stage leads to people talking behind the scenes; it raises suspicion in the music business and music journalism. People are starting to notice the extreme difference between the duo’s singing voices and their accents during interviews.

Plus, Rob and Fab themselves are getting tired of it. Understandably. It’s not easy to carry the weight of such a monumental lie, much less to do it so publicly, much less when you feel you are being cheated out of something you deserve. They came into this whole thing thinking of themselves as singers, after all. So in November of 1991, they demand to be allowed to sing on the next album. Their producer fires them. Rob gives an interview to the Los Angeles Times in which he fesses up to the scheme. And the whole thing comes crashing down. There will be no next album. The Grammy for best new artist is revoked. “We sold our soul to the devil,” the duo declares at a press conference where they come clean to the world.

SCENE: MUNICH, GERMANY, NEW YEAR’S DAY 1988

A small recording studio. Two good-looking guys—and I mean, really good-looking, like being too close to them makes you uncomfortable—are fumbling their way through an audition. The song, naturally: “Girl You Know It’s True.”

The guys are … well, they’re not doing great. They are fucking handsome, though.

And there’s a studio guy. A producer. Frank Farian, a name that like everything else in this story, sounds like I made it up (actually, he made it up; his real name is Franz Reuther). He looks pretty much exactly like a 1980s studio guy: wavy hair, small eyes, good tan, ostentatiously white teeth in a wide grin, which is to say that if you start the movie with this scene, it will be obvious to everyone who the villain is going to turn out to be.

Rob and Fab have been trying to make a go of it as a pop duo in Germany. They have some songs, though pretty much no one has heard them. They want to be stars. And here’s this guy—Frank Farian—who wants to make them stars. He’s also offering them money, which they very much need. Farian has a check for them, and a contract, and an idea. Time is of the essence, he insists, they need to get this video filmed and do so some shows, we’ll worry about the vocals later. Who has time for fine print when your dreams are being dangled in front of you? When you’re hungry and someone has food?

The thing about selling your soul to the devil is that it’s easy to insist you’d never do it, but even easier to actually do it when the devil offers you everything you’ve ever wanted.

MONTAGE: 1988-90, ALL OVER THE WORLD

What’s crazy is that Farian’s idea works. And it works better than anyone could have realistically hoped.

“Girl You Know It’s True” is a hit, first in Germany, then across Europe, and eventually in North America. Rob and Fab are stars, in a hurry, with all the trappings of stardom. Hotel-room parties and adoring crowds. Munich. Berlin. London. New York. Arista Records signs them—well, signs Farian, who owns Milli Vanilli. They meet Clive Davis. They are on the same label as Whitney Houston. Rob and Fab keep asking about when they’ll get to sing their own songs. Farian keeps saying yeah, yeah, we’ll talk about it, later, later. Things get bigger and bigger. Their album sells 7 million copies in the United States, 14 million copies worldwide. All four of their singles climb toward the top of the charts. They win a Grammy for Best New Artist. Weird Al parodies their hits:

Lots of people are making lots of money. Milli Vanilli is a bona fide phenomenon. It’s more than anyone could have hoped for. The duo are on top of the world, but they’re not happy. So naturally, this montage includes alcohol. Cocaine. Lots of passing out quietly in empty hotel rooms at the end of another whirlwind day. A gulf widens between who Rob and Fab are and who they appear to be, who they are paid to be.

SCENE: SOMEWHERE IN EUROPE, THE 1960S & ’70S

The other crazy thing about Farian’s idea is that he has done it before.

Here’s a scene for you: a young Frank Farian, walking out of the restaurant where he cooks, chasing his dream of being a singer, of being a star. You can see it: he throws an apron in the trash bin as he heads out the door.

But it doesn’t work. He records some songs, but has little success. So he makes a new plan. He records and releases the song “Baby Do You Wanna Bump” under the name Boney M. Then he hires singers and dancers to form a pop-disco group of the same name. Someone else becomes the front man for concerts and videos, but Farian himself does the vocals for all the group’s albums.

People eventually figure out that the supposed front man isn’t actually singing, but no one really cares. Maybe because it’s disco. Maybe because although Boney M is popular, they never reach the heights of Milli Vanilli. At any rate, Farian has his blueprint.

SCENE: INTERVIEW ROOM, 2017

An older, wiser, sadder Fab, being interviewed on YouTube. It has been decades since that recording studio in Munich, since the disaster in Bristol, since the press conference in Los Angeles. Rob is gone. He dies in 1998 of an accidental drug and alcohol overdose, while the duo are preparing to go on tour to support a new Milli Vanilli album. The album is never released.

The interviewer is trying to make sense of the story, trying to get Fab to offer some new insight, but there’s not much sense to be found in any of it. What’s clear, however, is that the stretch from January 1988 to November 1991 is somehow irrevocable. There’s no coming back from what happened in those two-plus years. The heights were too high, things went too far.

Milli Vanilli tried to come back, certainly. After Rob came in from that balcony and went through rehab, the duo recorded an album with their own voices under the name Rob ‘n Fab. They put a brave face on things, tried to own their new images, tried to be self-deprecating about the scandal:

None of it worked. Their album flopped, selling only about 2,000 copies. Rob sank back into depression and drugs. He spent time in jail; Fab bailed him out. It didn’t matter.

Talking about it all now, Fab is wry, self-deprecating, but also, you can see, still angry, still wounded. He looks tired. You can see that he has spent his entire life talking about these same events. He’s told the story a hundred times, a thousand times. He will always be telling the story. It has taken a toll. He remains almost impossible handsome.

SCENE: GRAND RAPIDS, MICHIGAN, FEBRUARY 2020

This is the Adaptation approach to the story. An essayist, played perhaps by Nicolas Cage because why not, sits at a dining room table, pecking at a laptop, listening to “Baby Don’t Forget My Number” on repeat, hoping to find meaning in it and failing.

The song itself? The song this essay was commissioned about? It’s nothing. A trifling. A throwaway bit of late-1980s commercial pop nonsense. Deliberately, calculatingly positioned to take advantage of the rising popularity of hip-hop, it is so clearly the creation of a hitmaker, a producer who sees the path to making money. This is not a song written by a human being with some artistic vision, some story to tell.

Released in December 1988, “Baby Don’t Forget My Number” was the duo’s second single and first of three No. 1 hits. It ended 1989 at No. 28 on the Hot 100 Billboard chart, right between Breathe’s “How Can I Fall?” and Martika’s “Toy Soldiers,” and behind all three of Milli Vanilli’s other songs from that year. It’s nowhere near as good as “Blame It on the Rain,” nor as iconic as “Girl You Know It’s True.” It is a difficult song to listen to all the way though, much less on repeat. It’s easy to imagine the Nicolas Cage-portrayed writer growing increasingly frazzled, his hair increasingly wild, his desire to finish the essay increasingly urgent.

The lyrics are vague to the point of nonsense, both grammatically and metaphorically: “I see it so clearly that our love it’s so strong,” and then, “Baby love is stronger than thunder.” (A line one lyrics site transcribes as “don’t be stronger than a thunder,” which is only slightly more confusing.) The gist, I suppose, is that a true love can withstand a misplaced phone number, or at least that’s the story I gather from the video, in which a chance encounter leads to the gift of a phone number, but then the paper bearing that number blows out the window, where it is stepped on by a passerby who gets into a cab with the number stuck to his shoe, so Rob and Fab pursue him on bicycles, all while the woman whose number it is waits forlornly by her phone, flipping channels, and every station is tauntingly showing black and white footage of people and apes and cartoon characters on the phone. Whew. It’s a lot. There’s also a lot of footage of the duo dancing, all lip-sync and shoulder pads, on what looks like a stage that has been set for an elementary school variety show, with an industrial city skyline and … a moat? That Rob and Fab emerge from in some kind of weird birthing image? The Nicolas Cage character in my movie has no idea what to say.

But here’s the thing about the Milli Vanilli movie: it’s probably too late to make it. It’s hard to imagine convincing 2020 audiences that this is a scandal worth caring about. It feels downright quaint in this current moment. The other reason you can’t make this movie is that all of the endings suck. At the end of the video for “Baby Don’t Forget My Number,” the pair finally chase down the passerby only to find that the number is no longer attached to his shoe. But plot twist! Their quest for number (searching high high high and searching low low low) has led them right to the woman’s building, and they run into her just as she’s emerging, having given up on waiting for that phone call. In the real life Milli Vanilli story, though, there are no happy twists at the end. Rob comes in from that balcony and gets help, but he dies anyway. Rob and Fab record their album, singing for real this time, but it is terrible and no one buys it. The guys who did the vocals for Milli Vanilli, Brad Howell and John Davis, try the same thing, recording an album titled The Real Milli Vanilli, but it is also terrible and no one buys it. Fab insists they were talented singers and Farian took away their dreams, but it doesn’t look like even he entirely believes his own words.

Probably the place to end the movie is where we started, back on that stage in Connecticut, right before the song glitches. Sure, nothing is real, and the deal with the devil has already been struck, and the devil will always come for the part in the fine print, but at that moment at least everyone can still pretend they believe in what’s happening. The end is coming. It’s closer than anyone realizes. But for now, the spotlights are on, and the cameras are rolling, and the music is loud, and everyone is having the time of their lives.

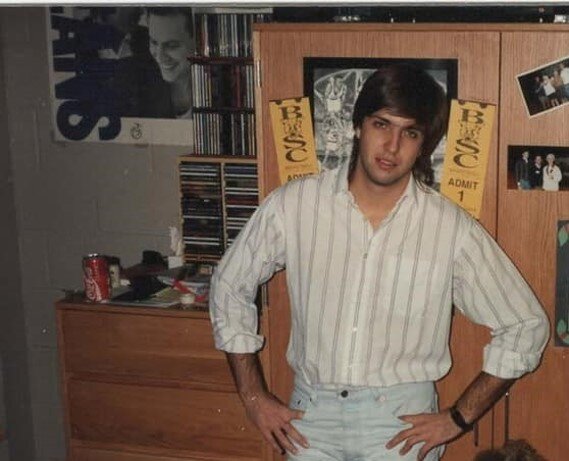

Amorak Huey (pictured in November 1991, the same month as Milli Vanilli’s confessional press conference) is author of the poetry collections Dad Jokes from Late in the Patriarchy (Sundress, forthcoming in 2021), Boom Box (Sundress, 2019), Seducing the Asparagus Queen (Cloudbank, 2018), and Ha Ha Ha Thump (Sundress, 2015), as well as two chapbooks. A 2017 NEA Fellowship recipient, he is co-author with W. Todd Kaneko of the textbook Poetry: A Writer’s Guide and Anthology (Bloomsbury, 2018) and teaches writing at Grand Valley State University in Michigan.