first round

(2) Lipps, Inc. “Funkytown”

spanked

(15) E.U., “Da Butt”

270-102

and will play in the second round

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/11/23.

amy rossi on “funkytown”

It’s nighttime, and two women are standing in a parking lot, one in a Halloween disco dress repurposed for a night out and the other in actual vintage 70s attire. They’re shiny and damp from the humidity and intermittent rain, and also they’re a little buzzed.

The Ford Fiesta they’re waiting for drives by them at a remarkable speed for a parking lot, despite them waving. Despite the fact that the driver is Disco Dress’s boyfriend, not a stranger. They run after him, laughing uncontrollably, and finally they are in the car.

“I need to hear ‘Funkytown’ right now,” the one in the vintage dress says.

*

The first time I heard “Funkytown” was in a commercial—one of those two-minute long deals that accompanied the 90s programming I watched with my sister on her personal television. This was, in fact, how I learned about a lot of music: through osmosis, each song blending into the next in such a way that if I heard the it in the wild, I was still expected the two key lines to melt into something else: Beach baby beach baby there on the sand, rock me gently rock me slowly, I heard my mama cry I heard her pray the night Chicago died—all these hits for $9.99, then audition other great albums from our collection.

Which is to say, I did not actively seek out “Funkytown.” It found me. Eventually it just became a part of my world in a way I did not question, the same way I absorbed state capitals.

The first time I heard someone else invoke the song, a boy in my eighth grade computer class asked a girl if she would take him to Funkytown as a joke, to be mean. I remember reporting the incident back to my sister, equally confused about how a popular boy could also know this old song that we knew and how someone could use the lyrics of “Funkytown” for ill instead of good.

That’s not what Cynthia Johnson was singing about.

*

“Funkytown” was the song of summer in 1980. According to funkytown.com, “The obituaries for disco were being written; Lipps, Inc. put the funeral on hold.” (The four paragraphs on that homepage are so succinct and eloquent that I feel an added pressure in writing this essay—the book on “Funkytown” has been written and I better be damn good if I dare add to it.)

Like all good songs of summer, “Funkytown” broke down walls. You could call it a one-hit wonder, but the emphasis would be on the wonder—because truly, how wondrous to make a song that had something for everyone.

It was steeped in disco but it pulled in other influences too, and it reached number 1 on the Billboard Hot 100, number 1 on Billboard’s Hot Disco Singles, and number 2 on Billboard’s Hot Soul Singles. Our writer at funkytown.com tells us the song “knew no musical, racial, or gender barriers,” and it wasn’t beholden to geographic ones either: “Funkytown” was a number 1 hit in Norway, Israel, Canada, Austria, France, New Zealand, Switzerland, and Spain.

For one summer, everyone could go to “Funkytown.”

*

Depending how you punctuate it, the lyrics to “Funkytown” are about five sentences long: The narrator wants to make a move to a town that’s a better fit, one that matches their energy level, they’ve been talking about it, they’ve got to move on, and will you take them there?

It’s laid out as a simple enough problem, but anyone who has ever been in that spot knows how many layers lurk under those words. Anyone who has ever hoped against hope that the problem was where you were, not who you were.

I spent most of my 20s trying to make a move to a town that was right for me. Less than two weeks after graduating college, I left suburban North Carolina for Boston. Much like the narrator of “Funkytown,” I wanted a place that would keep me groovin’ with some energy, and it seemed like everyone around me was segueing artfully from graduation to wedding planning. The city was the place to go.

And for a while it was, until a toxic mix of comfort and malaise settled over my late 20s. I could have this job forever. I could date this guy forever. I could rent this below-market apartment forever.

I started talking about what could be next, mostly to myself, and even then, I could feel how easy it would be for this to be all talk.

Gotta move on, gotta move on.

I ended up in graduate school in Louisiana. The thing is, I knew I was only going to be there for three years, and you can’t really find the Funkytown of your heart if you already have one foot out the door when you get there. And all the things I was running away from were still there, because it turned out the problem with me was me.

I didn’t plan to go home to North Carolina after graduation. I hated saying goodbye every time I visited, it got harder each year, and still, I applied for jobs in Chicago, DC, Boston, Philadelphia.

Instead I ended up back in the Raleigh suburbs, not because I chose to but because my lease in Louisiana was up, I hadn’t found a job, and I was almost 32 years old with nowhere else to go.

*

While I can trace my introduction to “Funkytown” to a commercial, its most persistent presence in my life comes from the video game Dance Central. There was a strikingly long period of time where, if the night went late enough, my sister would fire up the game and be ready to dance until dawn. This is still something that could happen.

My sister is not an incredible dancer, but she is an incredible learner. She would absolutely demolish her Dance Central competition because she was so technically proficient, it didn’t matter what flair, natural ability, or fluid motion the other dancer brought. Heaven help you if you thought you could win a round of “Funkytown.”

*

“Funkytown” was written by Steven Greenberg, a producer and DJ living in Minneapolis. He says he wrote it based on his own desire to get out of a scene that felt too vanilla and break open in the vastness—the funkyness—of New York.

Cynthia Johnson’s voice is the one you associate with the track. She was also living in the Twin Cities and her vocal highlights the tension of the song’s argument: Minneapolis isn’t New York, sure, but this scene also housed a voice and presence like hers, the same scene that gave us Prince; the first band she played in, Flyte Time, would eventually become The Time.

What depth of funky do you miss when you’re busy longing for something else?

*

After I had been living at home for six months, temping in a role similar to one I used to do for twice the money pre-master’s degree, my old job in Boston came open. I applied for it, did the first-round interview, talked to an old colleague about what it would mean to come back.

What it would mean to leave.

And that’s when I realized I had already made my move to the town that was right for me.

I never intended to end up back in the place where my parents lived, the town I’d moved to at age eight. But after a decade of living away from my family, I could not make myself say goodbye again. I knew too much now. My parents were getting older. And anyway, my brother had just moved across the country. It was his turn to go.

It was my turn to stop talking about movin’ and realize I was where I needed to be.

*

Steven Greenberg found opportunities with the success of “Funkytown.” The song has been covered by Kidz Bop, VeggieTales, and Alvin and the Chipmunks, among many others. (The absolute soullessness of the Kidz Bop version uncomfortably highlights the yearning and dissatisfaction in the lyrics that the arrangement and vocal power of the original contrast against.)

The song has appeared in soundtracks for films ranging from History of the World: Part I to Ma to Minions: The Rise of Gru. He calls the song “the daughter he never had” and spent years fighting for its termination rights under copyright law—the right to own his “Funkytown.” It’s very much a part of his life still, as he approves most of the song’s commercial uses.

He lives in Minneapolis.

*

My parents moved recently to live near my brother and his children, something none of us ever planned for when I came back here. Someone asked me what it felt like, to have moved and stayed in part for them and then to have them leave.

Of course I miss them, and I miss my brother and his family. Maybe adulthood is all of us never being in the same place. But I don’t regret my choice to come back for a second.

For a while after my return, my sister was open about the fact that she didn’t trust it, that she didn’t want to believe I was here to stay, a measure of protection to make it easier if I left again.

We’re still making up for the decade we spent living hundreds of miles away from each other, too broke or busy to make a visit happen more than once a year. Now we see each other multiple times a week. Now we even live next door to each other, a passage cut into our shared fence line so we can jaunt through our backyards and get to the other’s house faster. We are the stuff of sitcoms, minus the bite-sized conflicts. Now the trips we want to take and plans we want to make aren’t just things we talk about. It’s been six years, and I’m still here.

*

If you’ve seen a music video for “Funkytown,” you haven’t seen Cynthia Johnson. She is not featured in either version that became popular, nor in the album art. While the opening notes of the song are unmistakable, so is the sound of her voice on the chorus, the warmth and depth after the vocoderized verse, bringing us where we really want to go.

Johnson reunited with members of Flyte Tyme in 2018, as part of a series of concerts kicking off Super Bowl week in Minneapolis. They put their own stamp on it, including mashing up the beat with a groove from Prince’s “Erotic City.” In a video of the performance, Johnson is all joy and green fur coat and glimmering sequins. The concert is outdoors in an actual Minnesota January, and the streets are full.

“This,” she says, “is the new Funkytown.”

*

The truth is, I don’t know how to write about “Funkytown” without writing about my sister, and in fact, I chose this song out of everything on the list because she loves it. Because I wanted this to be a gift. Because I don’t know how else to express how lucky I feel to have her in my life. Because I wasn’t doing great when I moved back, and she and her husband gave me a soft place to land. Because Lipps, Inc. offered a shared language and something that would make us think of each other when we were apart and something that we can crank up when we are together. Because no road trip is complete without “Funkytown,” complete with the Talk 2 Much and Hitch Hike moves from Dance Central. Because joy is important.

Because the best things are deceptively simple—whether that’s a five-sentence song or a relationship forged by birth—and that’s how they endure.

*

It’s nighttime, and my boyfriend is driving my sister and me back from the outdoor disco symphony concert that was amazing but ended much too early, that was amazing but didn’t even include “Funkytown.” I must rectify the situation.

I am shorter, so I’m in the backseat, covered in glitter and rain and sweat, scrolling through my phone until I find our jam. In the front are the two people who love me best. The people who make it not just a Funkytown, but a funky home. One singing along with me, the other fully accepting his package deal.

What I know now is that Funkytown isn’t a place anyone can take you. I think you have to stop talking about it and just go, or you’ll end up wanting for the rest of your life.

It might not be the place you mean to end up, but I hope when you get there, it’s more beautiful than you think you deserve. You do, though. You do.

Amy Rossi lives, writes, and sometimes wears copious amounts of body glitter in North Carolina. Find more of her work at amyrossi.com.

wake up: brian a. salmons ON “DA BUTT”

August, 2, 1990, Thursday 9:30 P.M.: Today I got up, went to Driver's (he wasn't there), went home, got bored, played guitar, recorded noises with the jam box (didn't work), borowed [sic] Driver's recorder (didn't work), listened to the radio, and ate dinner. Well, here I am eating oreos, drinking coke and milk, and listening to E.U.'s album ‘Livin Large’. Hang 10.

FANTASIES

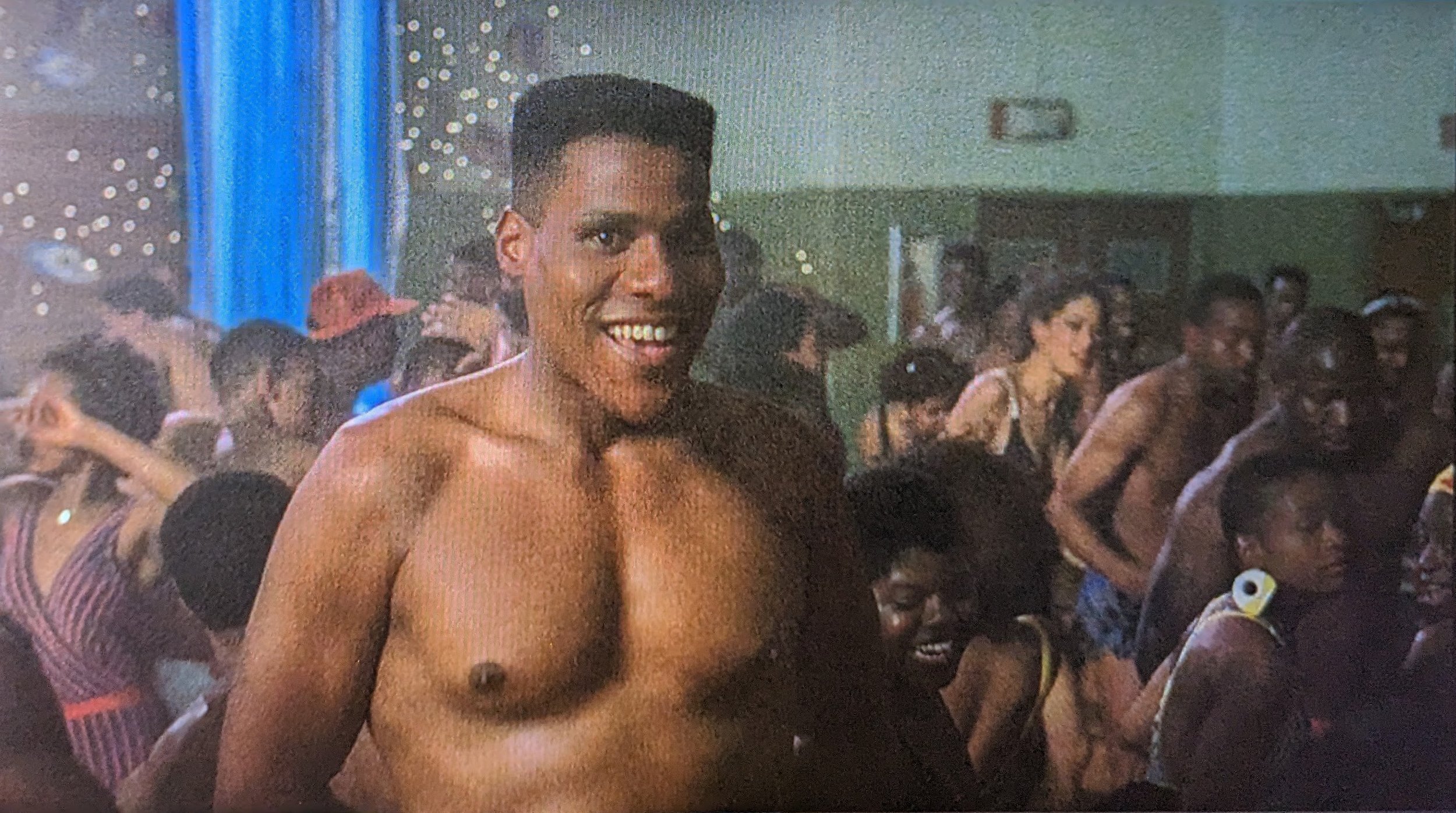

The Mission College homecoming dance scene in Spike Lee's 1988 film School Daze is the archetype of a boy's sexual fantasy. It opens with a slow zoom in on the guys, just arrived, removing their trench coats, revealing that they're wearing only swim trunks underneath. A banner on the wall above the stage declares the dance's theme—"Splash Jam". Accordingly, everyone is in swimwear: guys in trunks with no shirts, girls in one-pieces or bikinis. The beat starts, and the dancing. Cut to the stage, where E.U. is performing "Da Butt". The band’s wearing trunks, too, but with white shirts. Back in the audience, one of the guys—Grady (played by Bill Nunn)—is milling through the crowd, a goofy smile on his face, shirtless, when he spots Vicky (Kelly Woolfolk) dancing by herself and giving him unmistakable fuck-me eyes. Cut back to Grady, amazed at his own luck, and he does the thing where you look behind you to the left, then behind you to the right, because surely you're standing in some other guy's line of sight. Seeing no one, he does the Who me? head dip. Vicky's bikini top is purple, bottoms red and green, drop earrings large pink seahorses, and hair done up '80s-wild. Her response to him is to look even harder, with just a taste of a smile. Cut to Grady again, who gives a goofy Awww yeah! smile and nod. So they've hit it off, and we suppose they do "Da Butt" for the next three minutes because they're not in frame again until the song is over and Phyllis Hyman comes on stage to sing a slow number ("Be One"). Panning the crowd, we see Grady and Vicky dancing in each other’s embrace in a mass of sweating, near-naked bodies.

This is how I imagined all school dances were supposed to unfold. In my fantasy, I'd be standing alone by a wall, and then the hottest girl there would approach me, look me in the eyes, and ask me to dance. And we would. Then we'd probably definitely end up frenching.

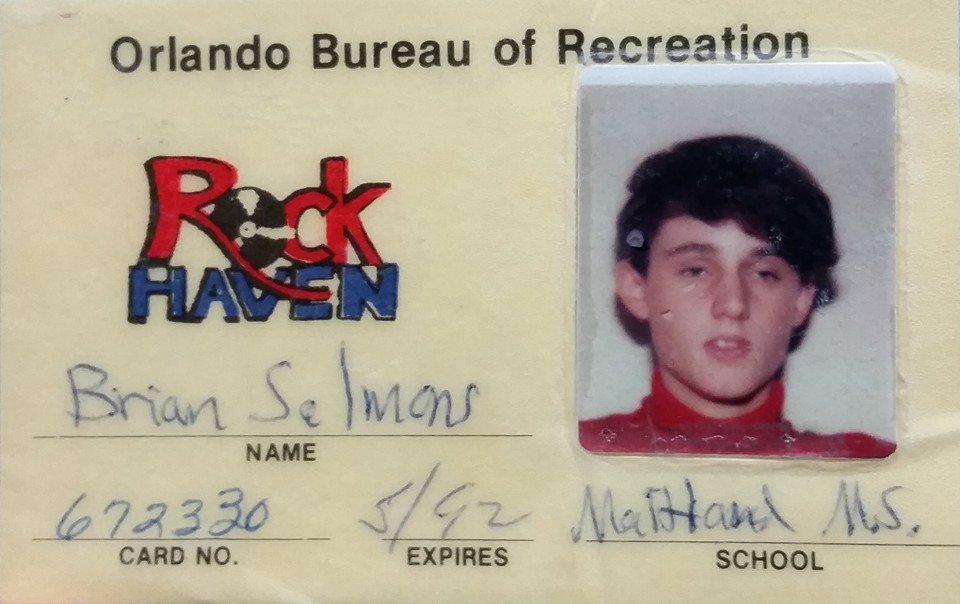

One Friday night in 1990 or 1991, at the City of Orlando's Bureau of Recreation's monthly "Rock Haven" dance for middle schoolers, this almost happened to me. For the special night, I wore my prized pair of black and white, cracked mud-patterned Vision Street Wear pants, a red polyester turtleneck sweater, and a thin gold-plated necklace with a Tweety Bird pendant. I combed my straight brown hair to one side in a giant "pooh". Too shy to talk to anyone, let alone ask a girl to dance or french, I stood by the railing to the stairs that led down to the dance floor, watching other kids dance, laugh, talk. My "Vicky" approached with a friendly and confident smile. I don't remember what she was wearing, but she sure looked good to me. She shouted something over the music, and smiled again, inquiringly. I hadn't understood her, but knew she must have asked Will you dance with me? So I said Yeah and she grabbed my hand and led me, blushing, through the crowd. I'd have followed her anywhere. Holy crap, I thought, it's happening! I couldn't summon the confidence to talk to her, I knew I couldn't dance with her, and I didn't know what I'd need to do with my tongue, but it was all happening anyway. She looked back at me once, as we walked, and smiled again. She was so happy, and that made me excited. I was going to do whatever she wanted. When we stopped, she pulled me in by the hand to introduce me to her friend. Uhhmm, I thought. Her friend wanted to dance but was too shy to ask me herself. She did a little wave from the hip, gave a scared little smile, and her eyes showed relief that I'd accepted the request. Hi, she cooed. She was not hot, not like her friend. To be more precise, she was a big girl. Not slim. I became fully aware of my error, tilted and shook my head apologetically while mouthing No, sorry, and walked back to my perch by the railing. I tried to act normal after that and avoid eye-contact with them, but I caught the eye-daggers the hot girl threw at me as she tried comforting her friend, the girl I had just essentially fat-shamed, now crying on her shoulder. This was not my fantasy.

ERRORS

For 34 years, I thought "Da Butt" was rap. It's not. Part of this error was because I had stereotyped the band based on their physical appearance (they're Black) and the song's impolite lyrics (the song is about women's butts, in case you didn't know). But the other part was that record companies and tour promoters themselves billed the band and the song as rap, or else as funk or R&B. In their defense, if they had promoted E.U. as what it is—a go-go band—they'd have been very bad at their job of promoting them to a national audience, since the phrase “go-go” had virtually no meaning to anyone outside of the DMV (District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia area). When it started out, go-go was DC funk's strategy to wrest the business of nightlife back from disco. Now, thanks largely to the #DontMuteDC social media campaign, go-go is the official music of the District of Columbia, codified into law in 2020 through the efforts of Ward 5 councilmember Kenyan McDuffie and DC Mayor Muriel Bowser. This little history skips everything in between and fails even as a basic description of go-go, but educating a new audience about go-go is not what I'm doing here. (The list at the end of this essay contains all that the reader needs in order to know what I now know about go-go.)

For as long as I’ve thought “Da Butt” was rap, I’ve also thought that was the only fame E.U. ever had. But they are no one hit wonder. Sure, "Da Butt" was their only song to hit the Top 40 of the Billboard Hot 100 (at #35). But "Da Butt" was just one part of a body of work—let's call that part the butt of that body, but a really fine butt—a body of work long admired and celebrated by fans. And that body was but one of many bodies, cranking on the dance floor that is go-go, one member of a community that is integral to being Black and from DC. E.U. is no Milli Vanilli, no PoP!, no special-purpose entity fine-tuned to sell albums and fill arenas with screaming fans. E.U., and go-go itself, was created by the people of DC, for the people of DC.

But I didn't know any of this at first. When my name was pulled in the March Fadness lottery, I went straight to Twitter and shared my thoughts about the song. Cocksure that everyone would agree, I said it was "possibly the worst song on this list" and "not the most endearing song". The first inkling of my error was a reply from a DC native: "Hoping the essay does Go-Go justice!" Go-Go?, I thought. The second inkling came after I’d done some basic research on go-go and told my wife that I was worried about offending an entire community, and possibly even the band members themselves, by the tack I had planned for the essay. She said, Yeah duh! You better do some better research. It’s been several months now, and I'm confident that I'm the biggest fan of go-go I can possibly be for someone who has still never been to DC, let alone to a go-go show. It's like that JoGo Project song: even though it’s not my city or my hometown, "DC's been good to me." But as much as I'd like to be the armchair-anthropologist regurgitating my plundered knowledge of go-go artists’ oeuvres and the historical context of the genre's birth and development—doing an outsider’s best attempt at justice—that's not what this essay is for.

TACKS

E.U.'s Livin Large (1989) was one of the few albums I mentioned by name in a diary I kept in the summer of 1990, when I turned 14. The diary was written in code and lay unread in a box until recently when I undertook the task of decoding it. It’s full of surprises, including that August 2nd reference to Livin Large. I’d forgotten just how much I liked that album and how well I knew the songs. I would thank the diary for being the only connection I have to that memory, but when I pulled up an image of the album cover it only took a glance to rekindle the memory of that attachment. When I look at it—those tribal, Olmec-esque faces block-printed over a solid yellow background, and a red stripe bisecting the central blue square, evoking the palette and geometry of a Mondrian painting—the dopamine rushes through me, an echo of the satisfaction I got decades ago from reproducing the faces with painstaking accuracy on my Trapper Keeper alongside sketches of the Def Leppard and Anthrax band logos that were more typical of my peer group. I even, vaguely, remember using acrylic paints, the ones that come in little, translucent plastic pots tabbed together in a row, to reproduce the album cover in full color on a large format sketch pad, and sticking it to my bedroom wall with thumb tacks.

The album art and the music—along with Candyman’s “Knockin’ Boots”, Soul II Soul’s “Keep On Movin’”, Young MC’s “Bust A Move”, and Snap!'s "The Power", songs I grouped together apparently on their Blackness and relative palatability with where I was coming from culturally—bonded with my fast-developing attraction to girls. It was the most potent concoction I could not yet name. My brain did its best in my dreams, some of which survive in the diary. The naked urge in these dreams is stated crudely and described with a comic lack of detail. Such stupid words. But I am glad that I remembered the dreams when I woke up and that I chose to write them down. Glad, because I believe that one’s self-perception should never stand unchallenged for too long. Thirty-plus years is too long.

It's a near certainty that "Da Butt" and the two other hits from Livin Large—"Taste of Your Love" and "Buck Wild"—were played at Rock Haven between 7:30 and 10:30 pm on any given second Friday of any given month in 1990 or 1991.

Walked in this place

Surprised to see

A big girl gettin' busy,

Just rockin' to the go-go beat.

The way she shook her booty

Sho' looked good to me.

I said, come here, big girl,

Won't you rock my world,

Show that dance to me.

If the DJ played them the night my fantasy almost came true, I was too distracted to listen. A lot was going on and I wanted to be a part of it, even if that meant drawing the line where I thought everyone else was drawing the line. I wasn't wrong. But what I did wasn't right. Even though it was a long time ago, I think a lot about the way I hurt that girl. I own the words I said and the things I did, and yet I know that I was also just following a script. Disrespect for women is everywhere. It's in the music about women's butts. It's in the things we say to our daughters but not to our sons. It's in the language itself, where the “feminine” is signaled by affixes and adjectives, like sports teams named the Lady Bears or the Rebelettes. And it's in cultural standards about who is attractive and who is not. Culture doesn't cause disrespect, it just makes it easier, creates a channel for it to sail through. Culture is the wind in disrespect’s sails. Maybe we're not all in the same boat, but we are at least in the same type of boat. A boat with a boom, rigging lines, and sails. We can sit in the boat, saying No, sorry and sipping champagne in our chic nautical gear and sunglasses, as the wind directs us, or we can take note, maneuver, and change tack.

SCRIPTS

In the slow dance scene that follows their first encounter, Grady talks to Vicky, mouths to ears, her fingers attentively stroking his shoulder blades.

I couldn't help but notice you in this bathing suit. You look goo...humph…nice. Real nice. Know what I thought about when I first saw you? Collard greens and corn bread, I ain't gonna lie to you. And Wilson Pickett. I mean you got like one of them 'In the Midnight Hour' bodies, baby. Hey, uh, so do you go swimming often? I can't swim a lick and I'm a Pisces, ain't that a trip? What's your sign? Nah, don't tell me, lemme guess. Virgo? No, no, no I'm gettin' Capricorn vibes from you.

Vicky rolls her eyes a couple of times, smiles, listening but not answering. She hears the self-editing in Grady's nonsense monologue, the compliments landing like horseshoes aside the stake. A lot is said and forgotten, heard and forgiven. Stupid words have no consequence in fantasy.

EDITS

There's a video that went viral for a minute in May 2019. It shows two men dancing outside the metroPCS store in the Shaw neighborhood of DC. This was the store at the center of the #DontMuteDC campaign. For over 20 years, the store's owner, Donald Campbell, had played go-go on a loudspeaker mounted to the building outside, a way to draw customers in to buy cell phones, but also “PA tapes” (fan-made recordings of live go-go shows, originally distributed on cassette tape). That April, some new, white neighbors threatened to sue T-Mobile (metroPCS's parent company) if something wasn't done about the loud music ruining the new vibe of the gentrifying neighborhood. So, under pressure, Campbell turned it off. But people noticed, and it became a whole thing: demonstrations, live go-go performances attended by crowds of fans and supporters, and a petition to allow Campbell to continue his one-man community tradition. Within two days, T-Mobile's CEO tweeted a sympathetic but PR-tuned backpedal, and the music was cranking once again.

One of the guys in the viral video—the white one and, honestly, the real star of the video—hasn't been identified as far as I know, so I feel justified in making up his backstory. Before he earned his two minutes and six seconds of fame, he walked past Campbell's store every day after work, wearing his khaki three-piece suit, messenger bag over his shoulder, hearing the music but not giving it much thought, and certainly not a critical one. After #DontMuteDC, being the open-minded, woke liberal that he probably is, he turned his attention and engaged with it. Hey, this is fun. Why not?, he thought one day as he saw another man, who was Black, dancing to a Suttle Thoughts song on the sidewalk outside the store. The white man danced like a Muppet ballerino. Pedestrians went on with their business, except for one woman with her phone out, filming, and dancing with them. Another man, Devin Wheeler, host of the DC-area television program One Honest Nation, noticed the scene from his car and filmed it for the world to see what happens when you take note, and change tack.

FANTASIES

I'd like to believe that if I had the chance to redo that night at Rock Haven, I'd dance with the hot girl's not-hot friend. And I wouldn't care whether or not she was hot. What mattered was that she was into me, and that we weren't that different. Together we'd do a shy and weird dance. When we finished, we'd offer awkward smiles back and forth, say nice things, think about frenching. Then she and her friend would go off to dish about it, while I hit the dance floor again, by myself, bustin' loose, like a white man in a three-piece suit on a sidewalk in Shaw. Confidence level rising, I'd even gain the courage to go back to her and ask for another dance. She'd say Okay! and I'd take that girl out on the floor and have a great time. I'd be a genuine Grady, saying a bunch of stupid things, asking a bunch of stupid questions, making her smile, laugh even. And then we'd kiss, gracelessly. With excessive tongue. I'd finally find that it's actually not hard to do. You just shake-a shake shake the whole night through, or at least until 10:30.

LIST OF SOURCES

E.U.'s 1977 album, Free Yourself, their 1982 album, Future Funk, and their 1989 album, Livin' Large

E.U.’s 1988 music video for “Da Butt”, https://youtu.be/FShE0VifCYs

Video of Glenn Close Doing "Da Butt" dance at the 2021 Oscars, https://youtu.be/Z-RovCOajc8

Spike Lee’s 1988 film, School Daze

Chip Py’s 2022 book, DC Go-Go: Ten Years Backstage (The History Press)

Kip Lornell’s and Charles C. Stephenson’s 2001 book, The Beat: Go-Go's Fusion of Funk and Hip-Hop (Billboard Press)

Walker Redds’ circa 2021 video, Go-Go History, Volume 1, Featuring Sugar Bear from Experience Unlimited), https://youtu.be/dumqi3tEC7I

DC Public Library’s video series, “Teach the Beat: GoGo Sound of Summer”, https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLu-TWTa5uhuqHlvo1bsGxCSIi6j6OF7nF

Washington Post video feature, "Go-go music returns to Shaw’s Metro PCS store after #DontMuteDC protests", https://youtu.be/2dMdvh4ar3E

David N. Rubin’s 1990 video documentary, “Go-Go Swing”, https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLiueG30w0DZWwZmdSJWlJN24ox3VRmQ3h

Howard University’s and Fred Brown Jr.’s 1991 video documentary, "Straight Up Go Go", https://youtu.be/JsB2gQOXcoE

Video of E.U. performing live at the Capital Centre (Landover, Maryland), October 1987, https://youtu.be/4e514obqgC0

Video of E.U. performing “Da Butt” live on Club MTV Spring Break 1989, https://youtu.be/C_ytHKbeKeg

TMOTTGoGo’s 2010 video, "True Go-Go Stories - Maiesha & The Hiphuggers", https://youtu.be/YfIprzbeEe4

TMOTTGoGo’s 2016 video, “TRUE GO-GO STORIES | The Legendary Ju Ju House (EU, Chuck Brown)”, https://youtu.be/iS97LnzH71U

Daddy’sLittleBride™ instructional video on how to do “The Butt” dance, https://youtu.be/7qU5Vh2oPO4

BBC Arena 1986 video documentary, "Welcome to the Go Go", https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLiueG30w0DZULTtHG6SKSKIwg4SR5X0RA

Redd & The Boys’ 1985 music video for “Movin & Groovin”, https://youtu.be/Ee-A-Ercv7o

The Go Go Posse’s (Chuck Brown, Little Benny, SugarBear & Whiteboy) 1988 music video for "DC Don't Stand For Doge City”, https://youtu.be/VXYH4TqMYfE

Video of E.U. performing live on the Tom Joyner Cruise 2012, https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLiueG30w0DZX-1cJa-OydNEYplCy3sUrz

Brian A. Salmons still lives in Orlando. He writes essays, poems, and plays, which can be found in Qu, The Ekphrastic Review, Autofocus Lit, Stereo Stories, Memoir Mixtapes, Arkansas International, and other places. He also reads for Autofocus Lit. Find him on IG @teacup_should_be and Twitter @brianasalmons.