first round game

(6) stryper, "to hell with the devil"

defeats

(11) jackyl, "the lumberjack"

77-52

Read the essays, watch the videos, listen to the songs, feel free to argue below in the comments or tweet at us, and consider. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchshredness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on 3/8.

PUH-POW: lawrence lenhart ON THE LITERAL SHREDNESS OF JACKYL, THE LAST REAL GLAM ROCK BANd

1. The drummer suggested I write a solo between practices. A solo, I figured, should start out slow, resemble the melody from the bridge. Resemble it less. And less. Until it lifts away from the song, destining for the fretboard’s cliff. When I sat to write my first solo, only one thing was for certain. I would find a use for the last fret: #22.

2. Mine was a Gibson SG Special. Yes, liked the one Angus Young played. Because of the SG, people assumed I was sympathetic to their AC/DC ravings. I had to explain how Angus, he was alright, but I couldn’t hack Bon Scott as a front man; the only thing worse than his daft lyrics was the gravelly throat from which they emerged. When Scott died, he was replaced by Brian Johnson. Also on the short list: Jesse James Dupree of Jackyl.

3. Maybe you’ve never heard of Jackyl, but you have found yourself sitting on a couch one Monday afternoon, flipping through that block of ten or so reality-based channels, hoping to find a show about business management (that’s not on CNBC), about pilgrimage (that’s not on CNN), about an enterprising marriage (that’s not on HGTV), about rock n’ roll (that’s not an infomercial). And there you arrive at TruTV’s Full Throttle Saloon. At the epicenter of the Sturgis motorcycle rally in South Dakota, the saloon is “the world’s largest biker bar.” And its most famous denizen is Jesse James Dupree. The show insists that you know: Dupree does his own stunts. Once a year, Jackyl emerges from their touring slump to rock the saloon’s batwing doors clean off.

4. To watch the show is to know Jackyl’s fanbase. Or maybe you don’t have cable, and your only television is reserved for classic video game play. If you’ve ever played Road Rash, the second-best vehicular combat game ever (the first best is Twisted Metal [1]), then you know that if you reach the finish line (and that’s a big if: see the name of the game), your helmeted avatar is received by a debaucherous crew of grungy party-harders whose briefly documented antics push the limits of PG-13 (“Teen”).

Imagine the Full Throttle Saloon at Sturgis is the ultimate finish line, and that the annual Jackyl show is the ultimate finish-line party. (Click here to upgrade your imagination’s RAM.)

5. At a concert, “solo” almost always means guitar. Sure, there are exceptions: Claypool’s bass (/whamola), Questlove’s drums, Ben Folds’ keys. By and large, though, the solo you’ll be talking about on the way home from the concert—the one whose high-speed scales, pinched harmonics, and whammy assault pinned you in place, gobsmacked you—is the one that was captured by the pickups of a guitar. Trust me when I say: beer sales were nonexistent during Derek Trucks’ fifteen-minute solo at The Allman Brothers show.

6. The first time I heard Jackyl’s “The Lumberjack,” I knew one thing and suspected another. A: This “solo” is not guitar. B: Perhaps it’s the throttle of a Harley. In retrospect, the context clues were all there. Of course it’s a chainsaw solo!

7. At Northern Arizona University (where I teach), players’ touchdown celebrations are less exuberant than the Forestry Department’s end-zone choreography. For each touchdown, the crew buzzes off a cross-section of a ponderosa pine. Go Lumberjacks!

8. I remember watching Home Improvement with my father, Tim Allen instructing Zachery Ty Bryan (Brad) on proper grunting etiquette in the garage during revving rituals. According to Time, Tim Allen’s simian grunt is the #1 “Unforgettable TV Sound.” Dad—who with Mustang and Shelby, Corvette and Thunderbird, Caprice and Impala, his many cars and counting, in borrowed barns and driveways, in our county and not—wished that I’d ape his enthusiasm for all things engine. He wanted me to grunt. But he must have realized early on: I was a Mark, not a Brad. Wikipedia says: “Mark was somewhat of a mama’s boy, though later in the series… he grew into a teenage outcast who dressed in black clothing. Meanwhile, Brad became interested in cars like his father…”

9. My grandfather liked cars too. He bought, used, and sold his cars at a rapid pace—something like six a year for twenty years. When the government placed a moratorium on commercial production of automobiles during WWII, it was only natural that Pap would chase GM’s newest vehicle, the Staghound, from the production line to Germany. We joke that the onset of Pap’s chronic leg pains coincided with the realization that he would have to march (rather than drive) through the European countryside. For four years, he sped through the Ardennes behind the wheel of armored Staghound scout cars, hurled the steering lever of M4 Sherman tanks, and swiveled the handlebars of his Harley-Davidson WLA as an MP at the Nuremberg Trials. Notice in his photograph below, the way he focuses on the mortality of the scout car: its front tire missing, back tire chained, snow melting into its exposed engine. The corpse seems to just be getting in the way of a good shot. For him, cars were more precious than life itself.

10. Jackyl’s self-titled debut was released in 1991, and not in the eighties as many would suspect. They were the last credible contributor to the hair metal genre [2] (albeit with a southern rock/“redneck punk” influence). At a time when grunge was the rock du jour, Jackyl was an anachronism. They missed the memo (the obituary, really)—or they just crumbled it in their greasy palms and swallowed it whole.

11. For my second solo, I opted for a more intrepid delivery: hammer-ons, pull-offs, and even finger-tapping. Less than a quarter of the notes were picked, which meant, in the words of the bass player: “[I] really put that one through the fuggin shredder.”

12. Had I ever really tried to like motors like my father and his father? How intentional was my failure to participate?

13. I’ve always been mortified by the theater of the guitar solo—the miscellany of postures, staging of the silhouette, masturbatory play on the fretboard, the tongue outstretched and eyes wincing, all grossly co-opted and codified by capitalist product placement. Fuck Pepsi. Fuck Guitar Hero. A great guitar solo disintegrates the body. The head doesn’t exactly know what the hands are doing. The face loses control of all its muscles. The foot stomps, toes curl involuntarily. Every body part rocks in apparent autonomy. Maybe it’s something Catholic in me that prevents me from enjoying that level of disinhibition. Most embarrassing is the guitarist who would showcase their orgasm face (I’m looking at you, B. B. King) mid-solo.

14. For a while I tried playing that first solo behind my back at shows. I stopped when it had its intended effect: ironic worship. Modest crowds knelt before me, spiriting their fingers so as to exorcise the solo out of me. I was bad at having fun.

15. When Dupree plays the chainsaw, though, there is another level of satisfaction in the crowd. Something simian in them is awakened. Unlike every song that came before it, “The Lumberjack” can literally shred. [3] In fact, most live iterations of the song feature Dupree sawing a stool in half with the chainsaw. It’s his signature coda. The chainsaw is especially obnoxious in the acoustic version of the song.

16. If B.B. King (and later Peter Frampton) were trying to find ways to make their guitars speak, to be in civil conversation with the composition as a whole, then Jesse James Dupree’s chainsaw is meant to turn his music into an act of demolition. The guitar becomes a weapon; it has the potential to evolve into danger music.

17. The most dangerous band we played with at Club Angel’s was Womb Raider. The bassist, in particular, weaponized the neck of his guitar, swinging it like an axe at the front row, often striking Shannon in her breast. He spit on her too. She tried not to cry. We looked away.

18. While all other guitarists of the glam era played “axes” (Gene Simmons’ bass was literally in the form of an axe) Dupree’s technology—a saw, not an axe—was unique.

19. In a promotional video for STIHL chainsaws, a technician explains how he converts the saw’s throttle to RPM, RPM to frequency, frequency to notes, and arranges those notes using time delays to produce an ironic cover of “Silent Night.” There is nothing especially precise or melodic about Jackyl’s solo in “The Lumberjack.”

20. I go to the swimming pool at my university where the NAU Loggers practice logrolling. I hand the team captain my headphones and ask his opinion of Dupree’s solo. He’s not impressed. “He’s just kind of randomly revving it. Any one of us could do that.” I wonder aloud if any of them could play the chainsaw better than Dupree. A smile flickers across several faces. They’re clearly confident that they could.

21. Perhaps “The Lumberjack” isn’t pure anachronism. After all, wasn’t grunge responsible for the proliferation of the flannel lumberjack look? I would argue that Jackyl’s single is perfectly situated at the intersection of glam and grunge. In the opening skit of the music video, an older man sits in a rocking chair on his ramshackle porch, wearing overalls and that infamous buffalo plaid. A truck pulls up to the property, playing Jackyl’s other single, “I Stand Alone,” and the man rises with his gun. Things immediately de-escalate as Dupree occupies the man’s barn for an impromptu concert.

22. There are dozens of lumberjack statues and murals throughout the city of Flagstaff, most of them retired mascots from the university’s bygone marketing departments. All wield an axe. Some look like a manic Jack Torrance from The Shining, others like a stoic Paul Bunyan. There’s one bronze statue outside of the Student Union that students have dubbed “sexy Louie” (our mascot’s namesake), and there’s even a conspiracy that it’s based on a young JFK. The only active lumberyard in Flagstaff now is the brewery on San Francisco Street (called The Lumberyard). I ask Dave, the custodian in the Liberal Arts Building, about the day the lumber mill closed in Flagstaff. “What can I say?” he said. “We all got the axe.” Dave, who wears black tee shirts with his own sayings (“I hate tee shirts with stupid sayings on them,” for example) and looks like a ZZ Top sound technician, has only said one dead-serious thing to me in the three years I’ve known him: “These kids, they’re not lumberjacks. They’re not even close.”

23. Setting the chainsaw aside, “The Lumberjack” is a typical Jackyl song. Dupree wastes no time establishing his backwoods cred, channeling CCR’s “Born on the Bayou.”

I was born in the backwoods

Of a two-bit nowhere town

It checks out. Dupree is from Kennesaw, Georgia, a town that famously and unanimously passed a law “requiring heads of households to own at least one firearm with ammunition,” according to the Marietta Daily Journal. From there, though, the song becomes an exercise in confederate allusion and sexual innuendo:

I ain’t whistling dixie

No I’m a rebel with a groove

&

But I ain’t jacked my lumber baby

Since my chain saw you

This isn’t the first time these themes have come into collision in Jackyl’s oeuvre. Another of their music videos—for “She’s Not a Drug” (“…but if she was / she’d be better than cocaine”)—was banned [4] not because it was set in an orgiastic strip club, but because its principal dancer wore Confederate Flag lingerie.

24. I joined Instagram this past month to see what has become of the best shredders from my high school music scene. Unsurprisingly, Dom is still shredding [1] [2] (his equipment is pictured left). Chuck, though, has turned to cars (see his last 12 photo uploads, right).

25. I lay a cheap acoustic on the floor of my son’s nursery, see what he can accomplish with his army crawl, his fingers’ grip:

When I rewatch the video, I see in his acrobatics an innate desire to shred. I envy his apparent recklessness as the guitar creaks under his weight.

26. I worried for my wife that her delivery would resemble my mother’s. To clear the way for my birth, my mother shredded (OK, broke) her pelvis. Despite all the ways the body prepares for it—the way the joints soften and ligaments loosen, everything conspiring to allow the pelvic opening to, well, open—hers still snapped. To be fair, I did weigh ten pounds at birth.

27. In Yasunari Kawabata’s “A Saw and Childbirth,” a dreaming protagonist interacts with a postpartum woman. (“Indeed, how ample were the folds that hung from her belly!”) The woman says, “Giving birth to a baby is nothing at all.” Only, as soon as she says this, she is shred (OK, split) in two. Her next words: “Yes, let’s tell her that having a baby is nothing at all.” In the same story, that dreaming protagonist is “locked in battle” with that same postpartum woman. The woman wields a sword that looks like a saw “such as a lumberjack would use to cut down huge trees.” The dreamer calls the evocative weapon a “bright ornament.” Every time his sword “bit into hers, her weapon nicked and dented.” The fight scene seamlessly evolves into an origin story:

Finally it turned into a real saw. These words sounded clearly in my ears. ‘This is how the saw came to be.’ In other words, it was odd because this battle represented the invention of the saw.

In reality, the chainsaw was invented in the late 18th century to help with difficult childbirths. Before the ubiquity of the caesarian section procedure, chainsaws would cut through pelvic cartilage and bone to extract babies from the womb.

28. In “The Lumberjack,” though, the saw does not represent birth, but the death of hair metal. Within the song, it’s like we hear the saw splitting the guitar in half. It’s as if Dupree knows that guitar in the coming decade (and beyond) will never again signify what it once did. Songs will no longer yield to the minutes-long virtuosity and ego of a soloist. It’s like Dupree knows that he can saw the guitar right in half because the alt-metal/nu metal/rap metal scene forming in his wake won’t be needing it.[5] Jackyl knows: The nineties will be bereft of shred. Let’s just throw the throttle wide open one last time.

[1] No, you’re wrong: Mario Kart is merely the children’s version of Twisted Metal.

[2] The Darkness insistently excluded.

[3] Then again, the solo is the sound of the chainsaw shredding only air.

[4] When Jackyl was banned from a Georgia Kmart, the band played a free concert from a trailer bed in the store’s parking lot. Footage from the concert was used in the official music video for “I Stand Alone.”

[5] Sure, heavy metal acts like Metallica may have continued to shred beyond the days of glam, but for me, shred fled to a new genre through the abilities of J. Mascis.

Lawrence Lenhart is a founding member of Dead Within (2003-2007). His essay collection, The Well-Stocked and Gilded Cage, was published by Outpost19. His prose appears in Fourth Genre, Gulf Coast, Passages North, Prairie Schooner, and elsewhere. He teaches creative writing at Northern Arizona University, home of the “lumberjacks.

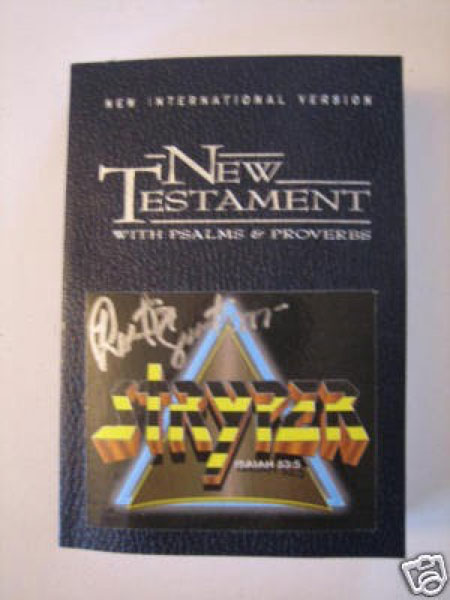

david legault on stryper's "to hell with the devil"

In the beginning there was Scripture, taken from The Book of Isaiah, verse 53:5: By His Stripes We are Healed. The stripes in question, of course, reference the lashes of a whip across Jesus’ back, the streams of blood pouring out of him, staining the dirt, the paradoxical healing that comes from taking on the sins of the world.

Actually, it begins earlier than that: though that verse is referenced on most STRYPER album covers, the verse was found as a meaningful connection to the STRYPER acronym: Salvation Through Redemption Yielding Peace, Encouragement, and Righteousness. In this case, the name came first: only later was Biblical meaning placed upon it.

Actually, it begins earlier still: the acronym was created after the name STRYPER was chosen. According to lead singer and guitarist Michael Sweet’s memoir, the name was chosen because it rhymed with the word “hyper:” because someone thought it sounded cool, connoted a certain energy and rock & roll attitude, because the name lent itself to stylistic choices: black and yellow stripes that cover nearly everything.

Perhaps that’s as good of an entry point as we’re going to find into “To Hell with The Devil,” with the entirety of the STRYPER catalog that must be addressed: Yes, you know them as the Christian Metal band. Perhaps you think of tight-striped spandex and throwing Bibles into the crowd. Perhaps you know them as two-time winners at The Dove Awards, or the guys who attempted to stylize “777” a numeric symbol that wasn’t tied to the satanic. But I love about STRYPER not for their faith, but in spite of it. STRYPER is not White Cross or Sacred Warrior or Lightforce or Holy Soldier because those guys suck: knockoff Christian bands without a sense of artistic vision, rather, they emulated it: becoming the Christian Iron Maiden, the Christian Metallica. These bands were not creating art but moderately acceptable imitations, taking music people liked and taking out the swears to appease worried parents, changing the word “Baby” to “Jesus” and acting as if that’s enough to make something meaningful. Only STRYPER comes out of this era concerned with music more than marketing, with being better than “secular” bands, with attempting to reach an audience outside of the Christian rock bubble. Perhaps this is why they were the first Christian rock band to go platinum, why they were the most requested band in the history of DIAL MTV in the prime of music video television. Perhaps this is why Christian groups and Televangelists spent more time protesting outside of concert venues than they did listening to the words being sung. What I’m trying to say is yes this is Christian metal and yes that is crucial to our understanding and appreciation of the band, but I’m also trying to say that their biggest priority was making something that would resonate in our bodies the way only good music can. What I’m trying to say is that this music shreds.

We speak of the devil

He’s no friend of mine.

To Turn from him is what we have in mind

The Czech Republic, where I currently live, is, spiritually speaking, the darkest country in the world. Roughly 85 percent of the country identifies as atheistic or agnostic. Despite the countless churches and cathedrals that have stood here for centuries, decades of Communist occupation turned organized religion into something dangerous to practice: large gatherings of people celebrating a higher authority—one with a Gospel which was meant to be shared and spread, one that spoke of overthrowing those who held its believers in bondage—was a sure way of drawing unwanted attention. Nearly three decades after the fall of Communism and the culture is still engrained with a distrust of authority, of organized meeting spaces, with sharing anything private or personal with the outside world.

I mention this because it is at least part of the reason I live here. I mention this because the school where I teach was founded in order to serve the small Christian population in this country. I mention this because the teachers at my school are paid through fundraising and support. I mention this because—even though my job consists of teaching humanities courses to advanced-level high school students, even though it sounds absurd, even to myself—my visa for living in this country lists my occupation as Missionary.

I don’t fit into the typical Christian mold, at least not in our current politicized climate: my views on the typical hot-button issues of choice or LGBTQ rights or social justice align more closely with your typical MFA graduate than they would with the picture in your mind when I say the word “missionary.” There were plenty of reasons for moving to Prague— it made sense professionally, creatively, and has overall been great for my family in all sorts of ways—but the primary reason, working at an international Christian school, was not a path I ever would have anticipated for myself. That is to say, my biggest problem with Christianity has always been Christians themselves, perhaps never more so apparently than in the last few years. Out of all the reasons I could be here, I consider my role in this school and this country to be representing a different side of Christianity: one that can perhaps better address the countless examples of hypocrisy and cynicism that I see whenever I watch the news, one that shows students how to follow the Gospel while still finding space to form your own opinions on the world, one that acknowledges the privilege we have been granted, one that chooses love over discrimination or judgment or hatred in all its forms.

Just a liar and a thief

The word tells us so

We like to let him know

Where he can go

Within a week of arriving in Prague, I received word that my first book of essays, a book that I first started work on over ten years ago, was finally being published. But instead of the excitement and accomplishment that I assume most people feel upon hearing this news, it filled me with pangs of loneliness. Most of the people with whom I could celebrate such news now lived on an entirely different continent, and though the people in this country were going to be supportive of the news, the idea of sharing the actual book with my new coworkers or students—a book that includes, among other things, references to a “Cooking with Semen” cookbook and my various (and ongoing) practices in vandalism—was out of the question. Which is unfortunate; the book won’t be found in a Christian bookstore, I’d argue that those values are at its heart: that I’ve often tried to fix the problems of my life through stuff, how I’ve created idols out of the labels I’ve put upon myself: teacher, writer, runner, musician, husband, father. The essays of the book are basically an exercise in pulling these labels away through a chronicling of my own failures, showing the failure in these roles, how my value in this world must ultimately come from somewhere else.

At least that’s my takeaway. The book itself likely doesn’t come close to addressing these questions in a way that is meaningful to a reader. It’s likely my own cowardice when it comes to sharing my beliefs, my fears of alienating others by talking about my faith—even as I move halfway across the world to serve a church-focused mission, I often have a hard time even admitting that I am a Christian in daily conversation.

So I find myself in a crisis of my own manufacturing: working at a school where I hope my views of Christianity can go against awful stereotypes, yet I am often uncomfortable in sharing those views. I’m afraid of sharing a mostly secular book within a Christian community, yet I’m equally afraid of exploring Christian themes completely for fear of alienating a secular crowd. I’m on the other side of the planet from my writing community and have just published a book that I don’t want to tell anyone about. Even now—in writing this essay and talking so frankly about my own beliefs and doubts—I find myself anxious for the possible real-world consequences of anyone actually reading this. If there’s any good that will come of this essay outside of assumed Shredness glory, I have to say that this is an earnest and honest attempt to make a case for my faith, a space in which I can feel confident enough to share a pretty big part of myself with you, to maybe feel ok in my own skin for a while.

To Hell With the Devil!

To Hell With the Devil!

There is something about the way this song’s chorus sounds both triumphant and sad, the way the guitar’s wail screams in agony as it rejects the sin that reaches into its world.

In Michael Sweet’s memoir, he writes about the complicated issue of Christian popular culture: how the artists don’t have to be as good because of a built-in audience, how the audience ultimately wants the original version and is therefore willing to accept an imitation, however poor it may be. In his words:

Stryper stood out from the rest of the Christian rock pack, I believe, for two reasons: we had a unique sound with great songs and we didn’t preach to the choir…It’s sad. You would think someone called to play music by God would have talent and creativity far beyond that of the secular world and would excel far beyond the norm, but that just wasn’t the case, or at least it didn’t seem that way to me. I think a lot of it has to do with competition. Stryper grew up on The Sunset Strip where competition was fierce. We didn’t just have to be better than other Christian bands but we had to strive to be better than the best of the best on The Strip. The Strip had the most critical fan base in the world. So for us to sing about Jesus and appeal to the fans on The Strip was quite unusual. We had to have great songs, a great look, and really shine above and beyond the rest. Our competition wasn’t the church band from down the street. It was Motley Crue, Ratt, and Poison… So as long as these Christian bands were moderately good, and inserted “Jesus” into a lot of their songs, they didn’t really have to try as hard to be accepted by most Christian rock fans. As a result, mediocre songs became good enough for a good handful of these groups.

The Bible talks about God’s children being set apart: in the world, but not of the world. This gets complicated, obviously, when the Christian message engages with popular culture: trying to appeal to widely held cultural ideas, but in a way that must be, by definition, countercultural.

This countercultural mission can be achieved in two ways. The first is by far more common: taking a popular thing and making a Christian version: DC Talk white-rapping about how a girl should act on a date, Kirk Cameron’s film career, or the countless book series including weird Amish romance novels, the Left Behind Series, or a wide range of self-help and—weirdly—business management guides. In short, this is not so much art as it is targeted marketing: creating a safe space for Christians who are willing to accept an inferior product that does not challenge, making something that will never appeal a non-Christian except for ironic mockery. It is preaching to the choir both literally and figuratively.

The second approach is to make art so compelling that non-Christians will still be drawn to it, and in this way, you are reaching a new audience, fulfilling a call to missions that asks us to go out into an unbelieving world, spreading the word of God. It may begin as countercultural, but if good enough, it actually shapes the rest of culture toward its style. The list in this category is incredibly small: it includes writers like C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien; it includes Veggie Tales; and yes, it includes the work of STRYPER.

When things are going wrong

You know who to blame

He will always live

Up to his name

Although not immediately obvious, I believe Hair Metal and Christian Rock share common threads: both are often lame, but they celebrate that lameness, bask in it. They share an earnestness that often makes me uncomfortable because I could never be that honest about anything. They go all-in to the point of excess: either raising their hands and shouting halleluiah, or through three-minute guitar solos, spandex, and laser light shows. STRYPER combines these in a way that seems natural: think of the rotating drum set at the end of this video, think of the way Michael Sweet falsettos the word Blame!

I realize now that the song’s greatest appeal is in its complete lack of shame, its refusal to apologize for its beliefs or its message. What I wouldn’t give to feel that free!

He's never been the answer

There's a better way

We are here to rock out

And to say

To hell…

Which is to say, the Bible tells us we are made in the image of God, that we should do everything we can to display that character. And what is God if not a creator? Tolkien talked about this as “sub-creation:” building worlds—creating art—as our clearest way of being like God, being in his image by doing the very things he does. I think this is one of the things we can do in art. I think is one thing religious artists have largely failed to do. I think this is what STRYPER has done to great success.

Or, to put it another way, I’ve long been afraid to create in this way because it feels so hypocritical: I am a selfish, vindictive man who often does the bare minimum that is required of me, more likely to run from my problems than deal with consequence—perhaps a bigger reason for moving to Prague than any of the reasons previously mentioned. That I crave recognition and prestige to a degree that isn’t healthy: I can tell you here that I still follow the careers of several writers who are working jobs I’ve interviewed for years ago, noting how much more I’ve published in the time since, how much jealousy burns for a career I often covet. I am the Michael Jordan of not answering emails, of never calling back. Even with two children and a wife, I put my own shit in front of others so often as to be shameful. Who am I to create worlds or share a message of redemption? How can I write something that can open more doors than it closes?

Or, to put in another way, I do not know the answers to the questions that I ask, but I know STRYPER makes me feel better about the act of questioning, about the possibility of one day getting over myself.

Or, to put it another way, I’d like to share with you now my favorite story in the Bible. It is from the Book of Acts, Chapter 17: the Temple of the Unknown God. To paraphrase, The Apostle Paul finds himself in the city of Athens, distressed at a city that he sees is full of idols. Here, he does not quote scripture at the Athenians, does not warn them of their sinful ways and the damnation of their souls, but instead, he quotes the Greek poets and philosophers. He spends time with their culture, learns from it, loves it. He references an altar he found that is inscribed: TO AN UNKNOWN GOD—a god the Athenians did not know, but still worshipped in case their gods did not cover every need, an emergency god to turn to when their own gods didn’t answer. It is this god that Paul argues is the same as his own. It is through this god that Paul finds connection and relationship outside himself. It is only through Athenian culture that he can reach the Athenians. Though most of the group still mocks Paul for his beliefs, some of them join him, as well.

Which is a roundabout way of saying I hope STRYPER has found a place in your heart: either musically or spiritually. Vote for them because they own the best color scheme in the tournament. Vote for them because Michael Sweet’s falsetto, because of Oz Fox’s guitar solos. Vote for them because God and The Devil are both here inside of me, but hopefully that struggle can reach out to you or to someone or to anyone. Vote for them because we all reach out for something misunderstood, because we all worship at the altars of unknown gods.

David LeGault's book of essays, One Million Maniacs, is now available from Outpost19 and includes more thoughts on Metal, as well as far too many of his thoughts on killer car movies. He has less hair and is significantly less Metal, but that doesn't mean he doesn't still own a synthesizer from his own rock and roll aspirations. Though he calls the Midwest home, he currently lives in Prague, Czech Republic.