(12) aimee mann, “one”

outmanned

(4) joan jett, “crimson and clover”

874-334

to win the march faxness national championship!

congrats to aimee mann and brooke champagne on their championship rings!

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Pacific time on 4/1/22.

david turkel on Joan Jett’s “Crimson and Clover”

“Joanie Jett! She’s got the greatest voice I’ve ever seen!” —DuBeat-e-o, 1984

I’ve named the play “Crimson and Clover” because I don’t know what it’s about. I want people to make up their own meaning, the way they do when they hear that song. I want them all to think about something different that’s true for each of them.

It’s 1998 and I bartend in a place called Hell and Joan Jett’s version is on our jukebox. Or “little Joanie Jett,” as we call her—an homage to Alan Sacks’ trash film, DuBeat-e-o.

When I ask customers what they think the song means, they tell me a dozen different things, as if the title itself were a sort of Rorschach. One says the song is about a girl losing her virginity. Another says that it’s clearly about shooting heroin, the blood mixing with the “honey” in a syringe. Still another informs me that Tommy James—the writer of the song—was a born-again Christian and that the crimson represents Christ’s blood and the three-leafed clover, the Holy Trinity.

The lead actor in my play, Tom, was of draft age in December 1968 when the Tommy James and the Shondells’ version raced up the charts. He tells me the song has always been about Vietnam for him: “blood and land, over and over again.”

My play is about none of these things. Though it’s written in three acts, which could represent the Trinity, I suppose. And it has some sex and violence in it. Also heroin. And camel spiders. And St. Francis and surfing and the C.I.A. Mostly it’s about a billionaire named Arson (played by Tom) who wants to become the first man in history to cross the United States, coast to coast, entirely underground.

It’s my first play and I’ve been in therapy since I started it. I ask my therapist—a Jungian—if he wants to know anything about what I’ve written. He doesn’t. “Isn’t it like a dream?” I suggest. “Couldn’t that be useful?” But he doesn’t seem to think so.

Tommy James claims to have simply woken up with the words “crimson and clover”—a combination of his favorite color and favorite flower—stuck in his head. But that story was disputed by Shondell drummer Peter Lucia Jr., who co-wrote the song. For Lucia, the title sprang from the name of a prominent high school football rivalry in Morristown, New Jersey (where he grew up) between the red-uniformed Colonials and the green-Hopatcong Chiefs.

And so, oddly, even at the ground-zero of the song’s creation, there’s dispute over what the words signify. Almost as if they were birthed twining a spell of some sort—weaving mystery and confusion into the air.

On the Songfacts message board devoted to “Crimson and Clover,” contributor after contributor offers what each insists is its sole, incontrovertible meaning. Kayla from Dallas writes, “The song is actually about a beautiful girl with red hair and green eyes, get it?” Rex from the ‘Heart of America’ begins his post, “It really surprises me that so few people have this right” before launching into the most painfully halting description of coitus, like a squeamish father tasked with the birds-and-bees speech.

However the title came about, the story of the song itself is well-established, if no less magical. As Shondell keyboardist Kenny Laguna tells it, the band had just lost their chief songwriter and the guys were pushing Tommy James to find somebody new, convinced he didn’t have the chops to write a radio hit himself. Five hours later, James and Lucia walked out of the studio with the recording of “Crimson and Clover”—James having played every instrument except drums on the track.

He then took the rough mix to WLS in Chicago, where he spun it for the head of programming as well as a top DJ to get their impressions. At some point during the visit someone at the station pirated a copy, and by the time Tommy James had returned to his car the single was on the airwaves in its raw, unmastered form, being hailed by the DJ as a “world exclusive.” Before Morris Levy, the infamous mobster who ran the Shondells’ label, could intervene, “Crimson and Clover” was already a hit and on its way to its ultimate destination at number one on the charts. Many who heard it that holiday season in 1968, thought James was singing “Christmas is over” on repeat.

At a Christmas party in 1998, an inebriated dancefloor collision results in my girlfriend tearing her ACL. We’re too fucked up at the time to know what’s happened. But when I wake up the next morning, she’s there beside me, crying in her sleep from the pain.

She’s been cast in my play as Looloo, a twenty-five-year-old recovering heroin addict whom Arson meets touring a new hospital wing. Looloo is a patient there because she skied off a mountain in an apparent suicide attempt. So, it makes sense that her leg might be in a brace, we reason. Sometimes things like this just have a way of working out.

“Do the math,” Lon from Providence insists. “It is a poetic masterpiece...about a plaid skirt...the girl he had a crush on in school wore...hence the colors maroon (crimson) and green (clover), and then the pattern over and over..........”

My girlfriend and I are among the half dozen or so co-owners of Hell, where, until the accident, she was also a bartender. She’s the real reason Jett’s 1997 retrospective Fit to be Tied is on the box, and why we frequently holler out, in our best Ray Sharkey impressions, “Joanie Jett! She’s got the greatest voice I’ve ever seen!” whenever it plays.

Sharkey portrays the title role in DuBeat-e-o: a movie director who’s on the hook to the mob for a new picture starring Joan Jett. In real life, director Alan Sacks (best known as a creator of Welcome Back, Kotter) had been hired to salvage botched footage from an attempted screwball movie based on the Runaways—the all-female, proto-punk band Jett founded with drummer Sandy West in 1975, just weeks shy of her seventeenth birthday. Sacks had fallen in with the L.A. Hardcore scene and his solution to the problem of trying to use bad footage to make a good movie, was to make an even worse movie about a megalomaniacal director’s fantasy of making a great one.

“See, I shot this film so that Joanie would come out looking hip enough to handle any situation. Understand?” DuBeat-e-o lectures Benny, the cough syrup-addicted film editor (played by Derf Scratch from Fear) whom he’s chained to an editing station at gunpoint. “I mean, that’s why I put her in every slimey, scummy situation of Mankind that I can think of, okay? I mean, the essence of my film—my film!—is that true talent, no matter where it comes from, has gotta come out—because it’s got fucking ENERGY! You understand?!...That’s why I’m the director! I got the vision, you prick!”

IMDB lists Jett as “starring” in DuBeat-e-o, but this is a Bowfinger-like deception, since she only appears by way of the archival footage Sacks was hired to edit, and as a picture adorning a wall in DuBeat-e-o’s seedy apartment. More accurately, Jett is hostage to the movie, her bottled image coopted to serve its baser designs; her ever-tough performance chops fronting the Runaways cut to look as if she’s delivering these efforts to please the leering countenance of The Mentors’ El Duce (who plays his slimeball self in the film).

And yet, perversely, it all works. Moreover, it works just as DuBeat-e-o, at his most deranged, said it would: Jett’s hipness—her ENERGY—rises above it all, untouched and unsullied. And the movie, either in spite or because of its many flaws (it’s really impossible to say which), truly exalts her.

In the 2018 documentary Bad Reputation, Jett—its ever-inspiring subject—avoids any mention of Sacks’s film by name, but merely shrugs it off as “some weirdo porn movie.”

Before I started tending bar at Hell, I knew next to nothing about Joan Jett, outside of “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll”—a single that peaked when I was eleven years old and inking “O-Z-Z-Y” across my knuckles.

I didn’t know about the Runaways or Jett’s affiliation with the Sex Pistols. Didn’t know that she produced the first Germs album and music by Bikini Kill. Or that she and ex-Shondell Kenny Laguna—her longtime collaborator and Blackheart producer—were forced to shill her hit-laden solo debut out of the trunk of Laguna’s car after it was turned down by twenty-three labels. In short, I didn’t know that Joan Jett was punk before punk and indie before indie.

But by 1998, not only do I know these things, forty-year-old Jett has recently turned up in a black-and-white commercial for MTV, flipping off the camera and sporting the close-cropped platinum-dyed hair that will become as iconic to that era as her black shag was to the seventies. She’s been going at it hard for more than two decades at this point, only to emerge looking fitter, tougher, sexier, more otherworldly than ever before, and I am becoming obsessed.

“And there was Joan in the black leather jacket,” Laguna says of their first encounter at the Riot House on Sunset Boulevard. “The way I remember it, there was razorblades hanging from it. And...I just never seen anyone like this. I was like, ‘Whoa! What is this?!’ And...I think I loved her right away.”

Ahhh, well, I don’t hardly know her...

“A little quiz for the Peanut Gallery,” posts Alan from Providence on Songfacts. “Crimson is my color and clover is my taste and aroma. What am I?” he asks, before adding, with a tacit wink, “And there is a reason Joan Jett loves this song.”

But I think I could love her...

Laura from El Paso concurs: “I have to say that when Joan Jett sings this song, for me it is impossible not to feel it takes on a whole new meaning. She is singing about ‘her’ and how she wants crimson and clover over and over.............”

And when she comes walking over

I been waiting to show her...

Joan Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” arrests us, not only for those parts of the song she’s altered, but also for what she’s kept in place: the pronouns of the singer’s object of desire. Though Jett has said this decision was about preserving the integrity of the rhyme scheme, the seismic impact of hearing one woman sing so intimately to another—unprecedented on popular radio in 1981—can’t, and shouldn’t, be overlooked. Not because the choice scandalized certain listeners (I mean, seriously, fuck them), but because for many others this was a revelatory and liberating event.

As Bikini Kill’s Kathleen Hanna puts it, “The first time I heard Joan I was in the car with my dad and it came on. It was ‘Crimson and Clover,’ and I heard that voice, and I was just like, ‘Who is this person?’ And then, when she would get to the pronouns and say, ‘she,’ I got really interested.”

At the same time, I think it’s important to take Jett at her word as a no-nonsense rock- and-roller simply working in the service of a great song. Certainly it’s true that, where rhyme was no impediment, she proved more than willing to make heteronormative adjustments. Case in point: her most famous cover off the same album, the Arrows’ 1976 tune, “I Love Rock and Roll”: “Saw her standing there by the record machine” became “saw him standing there.”

But what’s true in both cases is that Jett’s persona animates and subverts each narrative equally. Speaking for the eleven-year-old that I was when I first heard “I Love Rock ‘n’ Roll,” it was a novel and noteworthy experience to be confronted by a sexually aggressive woman describing her recent conquest of a teenage boy in such tough, conversational terms. Like Hanna, or Kenny Laguna, I distinctly remember thinking, Who is this person?

Jett describes her own approach to inhabiting songs this way: “Part of it is having fun, and part of it goes back to...being able to do everything. When you’re singing songs about love and sex, you want everyone to think you’re singing to them. Whether you’re a boy, a girl, a woman, a man—whatever you’re into, I can be that.”

My, my such a sweet thing

Wanna do everything

What a beautiful feeling...

“The greatest voice you’ve ever seen”—that superlative from DuBeat-e-o—has never been showcased to greater effect than 1982’s “live” performance video of “Crimson and Clover.” At minute 1:28, Jett seems to be singing in harmony with her own eyeballs. Yes, sing the eyes, you know exactly what I mean... I would argue that as much as keeping the word “her” matters to this cover, the potency of Jett’s rendition hinges on her phrasing of the word, “ev-er-y-thing.”

What’s brilliant about Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” is the way she both queers and straightens the song. Gone is the drippy vibrato and underwater warbling which threatens to make the original a relic of Psychedelia. In their place, Jett and Laguna have punched up the guitars and amplified the dynamic interplay between the breathy, epiphanic verses and the riotous bounce of its instrumental breaks. In live performance, at the dramatic crescendo—Yeah!—Ba da! Da da! Da da!—Jett never fails to let go of her guitar and raise her arms fist high toward the audience. “Crimson and Clover” is an anthemic rocker, as she embodies it—a song about connection, celebration, ecstasy.

But what truly distinguishes Jett’s version from the Tommy James and the Shondells’ original, is that Jett actually knows what she’s singing about; Tommy James didn’t have a clue.

“People ask me what it means?” James told a Youtuber who calls himself the “Professor of Rock” in a 2019 interview. “Two of my favorite words that sounded very profound when you put them together. And just a three-chord progression, backwards.” For Jett, on the other hand, the meaning is clear. In Bad Reputation, she envisions the song from the perspective of the woman she’s singing to: “‘Oh my God, she’s gonna take me home and fuck the shit out of me!’ That’s scary!”

I don’t make this comparison to disparage Tommy James; cluelessness is possibly the single greatest feature of his music. He recorded “Hanky Panky”—his first number one hit and one of my all-time favorite rock-and-roll tunes—having only heard a garage band’s cover of the original and remembering almost none of its lyrics. His chart-topper “Mony Mony,” from March of ’68, cribbed its title off the acronym emblazoned atop the Mutual Of New York building, which loomed outside the window of James’ Manhattan apartment. In both cases, his ability to imbue nonsense words with infectious energy and devilish intentions earns him Kenny Laguna’s praise as “the Led Zeppelin of Bubblegum.”

With “Crimson and Clover,” however, James needed a song that would do the opposite— launch him out of Bubblegum’s playground on the AM dial and into the burgeoning FM market.

And while he loves to tell the story of how the title arrived in his sleep and how the song was a deus ex machina for his band (“I think my career would have ended right there with ‘Mony Mony’ if there wasn’t ‘Crimson and Clover,’” he told It’s Psychedelic, Baby in a 2013 interview), the real truth is that Tommy James had spent nearly two years clocking an impending shift in the musical landscape. At an earlier point in the same interview, he describes the moment in February 1967 when he heard “Strawberry Fields Forever” crossover to an AM Top 40 station: “That really left an impression on me.” A new audience was emerging for whom Pop’s infectious energy was not enough. They were hungry for something beneath the surface.

Or, at least, the suggestion of it.

Not to be outdone by the Songfacts sleuths, I have my own admittedly less romantic view of the real meaning behind “Crimson and Clover.” Whether consciously or not, the title is a “Strawberry Fields” analog. Red and green, verdant and evocative—Crimson and clover, over and over is Tommy James’s Strawberry fields, forever.

This suspicion only solidifies with a listen to the whole Crimson and Clover album, which wears the influence of that particular Beatles’ song pretty thin over its ten tracks. "Hello banana, I am a tangerine,” Tommy James sings at one point, sounding like a narc trying to bluff his way onto the Psychedelic school bus.

But look again at the same three songs: “Hanky Panky,” “Mony Mony” and “Crimson and Clover.” All three open on an image of a woman in motion. All three turn on a chorus of indefinite but suggestive meaning. What truly separates them, and what also separates Bubblegum from Psychedelia (“Sugar, Sugar” from “Mellow Yellow”) is that the former uses innuendo to hint at a song’s true meaning, whereas the latter employs it to the opposite effect— suggesting that the song’s meaning is deeply buried and perhaps not even fully available to everyone.

All of which is to say that, while Tommy James certainly knows how to inject a song with implied meaning when he wants to, with “Crimson and Clover,” he is deliberately trying not to say anything. It’s a masterpiece of indirection. Like a shell game with no pea.

Stage lights rise on a young man hanging upside down, his head in a bucket. This is the character of Jeffery, the surfer in my play. He’s been imprisoned in an unnamed country by fascist goons who have mistaken him for a writer. He hangs like this for a few beats, and then his interrogator enters and grabs him up by the hair. That’s when the soundboard operator cues the song: Ahhh...well, I don’t hardly know her...

Joan Jett’s “Crimson and Clover” kicks off act two of my play. This is the real reason why I’ve chosen the title—I want the song to feel like it’s stitched into the very fabric of the text, so that no one will mistake it for a directorial or sound designer’s decision. Like DuBeat-e-o, Alan Sacks, Kenny Laguna, Kathleen Hanna, I want Joan Jett’s bottled light to illuminate my dim interiors; I want to claim some of that impossible energy of hers for myself.

But my director has other ideas about the power source we need to tap into for our production. A week before we open, he introduces us to Robert, his guru—a professor from his grad school days. Robert speaks at length in a haughty British accent on the subject of “vibrating at a different frequency”—a discipline which he believes, once mastered, renders an actor utterly captivating to audiences.

We’re gathered in a circle where the only language we’re allowed is the single syllable, “bah!” and we’re instructed on ways to “direct our sound.” First, off one wall. Then two. Then off two walls and through the window out into the street, like a bullet ricocheting. Bah! BAH! “Put your bah into your chests,” Robert tells us. Bah! “Now into your stomachs!” Bah!

I’m afraid to even look at my girlfriend, there in her leg brace across the circle from me. This is everything I promised her theatre wasn’t. The total opposite of Punk rock.

“Now, put your bah into your left foot,” Robert, the guru, prompts me, dropping to his knees so that he can rest his ear just below my ankle.

“Bah!” I shout.

He looks up and says in earnest, “Don’t yell. It’s not about volume. It’s about putting your voice into your foot.”

The next day, he takes the cast to a mall, where, at full voice in front of the Cinnabon, he describes the milling shoppers as “dead people.” Our job as high priests of the theatre, he informs us, is to remind them all what it means to be alive.

When Tom tells the guru that he finds the mall patrons “electric,” he is banished from the inner sanctum. Meanwhile, my girlfriend has hobbled off with one of the other actors to get stoned in the parking lot.

Eventually, I too shuffle away in despair and embarrassment. The guru’s visit has cost us two thousand dollars and we can no longer afford the boat we need for the climactic third act scenes on the underground river. It’s just as well. I’ve lost all faith in my play by this point. All my big ideas have turned into mush. The monologues I was so proud of, despite all my actors’ best efforts, ring false and contrived.

There’s only one scene I care about anymore. Over the run of the show, it will be the only scene I consistently emerge from the wings to watch. I wrote it in five minutes and thought nothing of it at the time. It’s just a breakfast scene with the whole cast present. Everyone gathers in the kitchen, trying to start their day and pass the butter around the table. Arson and Bell, the scientist, discuss plans to launch his underground journey from the secret lab she runs beneath Mount Weather. Ed, the CIA operative, tells a crass joke to Looloo and Benedict—a psychic who’s recently been helping Arson communicate with the dead.

Jeffery is the last to enter. He’s been in bed for days, horribly sick from his ordeal. He’s shaky on his feet and not really certain where he is.

There’s something about the rhythm of this sequence I got right. The butter, the stray fragments of dialogue and competing conversations. The entrance itself, which isn’t clocked by everyone at the same time, so that it’s like a musical breakdown with all the instruments cutting out one by one. The particular quality of the silence that follows, as Jeffery stands there swaying, and Looloo slowly rises to meet him. There’s something about the way the actors have to extend themselves to fill the gaps in this scene; that’s where the life is, I’m starting to understand, in those gaps.

This is my first real piece of theatre. No one thinks twice about it but at least I’ve figured that much out. In performance, you don’t hardly know what you’ve written until someone else tries to make your words their own.

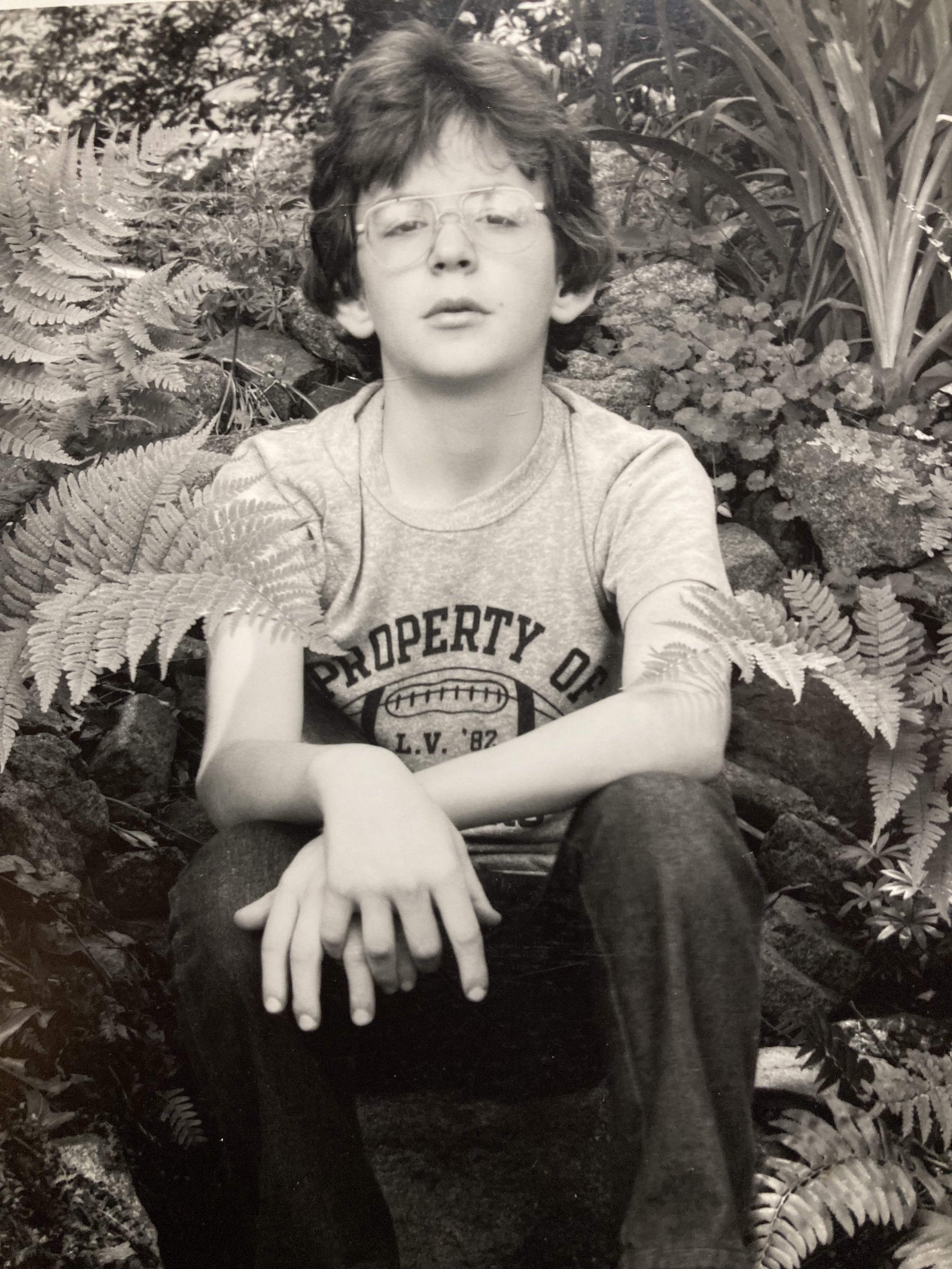

The author in 1982, the year Joan Jett’s cover of “Crimson and Clover” peaked at #7 on the Billboard Hot 100. Captured here in the wilds of New Jersey, without a clue in his mind that he is headed straight to Hell. And from there, eventually, Oregon. He will pick up bartending and playwriting along the way and would be pleased to know that he’ll one day land a gig writing about vampires for television.

NOT THE LONELIEST COVER YOU COULD EVER DO: BROOKE CHAMPAGNE ON AIMEE MANN’S “ONE”

Two can be as bad as one, it’s the loneliest number since the number one.

She first made herself known not through sight, but sound. What did she sound like? Like a cartoon bubble bursting over my head. Like the bright pop sound Andy Williams makes in the chorus of The Chordettes’ 1958 song “Lollipop,” sticking his forefinger into his cheek and uncorking the champagne bottle of his mouth. Half-believing I dreamed the pop, I stood up from bed at 2 a.m. and felt a slow leaking, as if my body had forgotten how to hold itself together. At first I thought I was pissing myself. Suddenly, about a gallon of bloody water emptied from my vagina.

My daughter was due in almost a month, but she’d be arriving today. Still, I had reasons to remain calm. The hospital was only one backroad mile from our house. My husband slept soundly next to my wet spot, but there was no need to wake him yet to pack a bag. I’d read that we wouldn’t need to leave till contractions were four minutes apart, and that was likely hours away. All I needed was my phone timer and something to do. And I knew just what that was. “Okay, this is good,” I thought. “I have papers to grade.”

It was the middle of the fall semester and I had subs to cover my classes, but I didn’t want to leave them with a full set of ungraded memoirs. Besides, I like reading student memoirs. What’s a “bad” one look like? Too self-centered? Too incomplete a narrative arc? Screw all that. My students share their lives with me. They may not completely plumb the depths of why things happen the way they do or what it all means, but they’re getting there. They open up to me in ways they may not with their parents, in ways that—holy shit—my daughter might also close off to me someday. Yes, I was already this far afield while timing contractions and commenting on my students’ uses of reflection and scene, entering grades ranging from A-minus to A-plus. Then, I was somewhere twenty years in the future: who would this early girl be, and what would she mean to me. I couldn’t imagine the answer; the question itself was terrifying.

In fact, the question required further distraction, so I scrolled through my DirecTV guide to where I usually find it: HBO. Paul Thomas Anderson’s Magnolia had just started—a perfect movie for the desperation I was masking. Then, I was nearly twenty years in the past, first watching the movie and hearing the dial tone as the song “One” begins, beep beep beep beep. The singer leaned on the word “one” so deeply, so coolly, “one is the loneliest number that you’ll ever do…” The opening film credits revealed a magnolia blossoming at hyper-speed, followed by the slow unraveling of sad, lonely characters I would spend the next three hours only half paying attention to. Like I said, I’d seen them all before.

Now I spend my time just making thoughts of yesterday.

She first made herself known not through sound, but sight. In my second year of college, my mom’s best friend Gloria burned me a CD with a homemade cover design. She often made me gifts like this, introduced me to R.E.M. and Radiohead and all the Gen X coolness I’d always been slightly too young for. On this CD, a long, lanky woman, blonde and cool-looking, like Gloria herself, wore a tankini and her name written in script across her body: Aimee Mann. Oh boy, I thought, another beautiful, blonde singer. But I trusted Gloria. She’d never married or had kids, and so from my purview her life comprised of great-art consumption, astute political commentary, and believing in me. She cheered my amorphous writing ambitions, even masochistically asked to read early drafts.

Gloria wasn’t an artist, but loved art in all its forms. She could name all the architects who designed her favorite buildings in our hometown of New Orleans, and she was fun; she knew every rooftop bar in town. Because my mother spent much of her adult life raising three daughters, three stepdaughters, and cycling through three husbands, she didn’t have as much time to slow down, pay attention. Whether or not a piece of art or music or film was beautiful didn’t much matter. My mother rarely analyzed, or let a thought or feeling linger. She accepted a breadth or dearth of beauty, and moved on. At that time, in college, I saw in these two women two discrete paths for womanhood. The Gloria path was glorious. Freedom, one-ness, living life mostly for yourself. Though my mother is no martyr, I feared choosing her path would mean my own martyrdom. To be encumbered, constantly needed and tired, having little time to contemplate art and the self in the one life I was living. I needed time. I wanted to write, to make art, like this childless, beautiful Aimee Mann.

Because I wanted to impress Gloria, I didn’t just listen to Aimee Mann, I studied her. I read somewhere that Anderson wrote the screenplay with Mann in mind, that he wanted his movie to be the equivalent of an Aimee Mann album. In that sense, the film was a cover of Mann’s musical oeuvre established in the early-mid 90s. The soundtrack’s first song, “One,” opens the film, and it wasn’t immediately my favorite. The song contains no images. It’s pure argumentative lament. When I first heard the album from start to finish, I was most gripped by the track “Save Me.” It begins with the lines, “You look like a perfect fit / For a girl in need of a tourniquet.” If you’ve ever really loved someone who’s damaged, or been that damaged person, it’s a perfect simile.

Anyway, “One” is an ostensibly simple song with simple lyrics. The relationship referenced is one where a presumed lover, or loved one, is gone. That’s all we know. When I first heard it, the English major in me found it fascinating to hear that one was a number you could “do.” As in: enact, or perform. The rest of the song felt pointless to deconstruct. “One” is lonely, “no is the saddest experience…”, yes, I get it. I remember sometime after Gloria burned the CD for me, I asked her what she thought of the song, to confirm if I was correct about it. She laughed and said, “Well, yeah, it’s sad, but ‘one’ isn’t always the loneliest number.” Given that I planned to take her solitary path, I was glad to hear it.

Over the years, as I dug further into Mann’s oeuvre, I learned “One” was a cover with interesting tweaks to the 1968 Harry Nilsson original. Mann’s version includes an electric guitar, and her tone makes the song’s argument more starkly than Nilsson. He sings “one is the loneliest number” like it’s a suggestion; when Mann sings it, “one’s” loneliness is fact. But what I love most about the cover is how much Mann relies on Nilsson’s voice, both at the opening and closing of the song. In the opening, just after the beep beep of the dial tone, we hear a male voice shout, “Okay, Mr. Mix!” Which feels totally weird and nonsensical. Turns out it’s Nilsson, from another of his tracks called “Cuddly Toy.” And as “One’s” final cryptic line concludes—one is a number divided by two—Mann’s voice recedes, and Nilsson’s enters again. He sings the following lines, which are not lyrics from “One,” but from another of his songs called “Together”:

And one has decided to bring down the curtain

And one thing’s for certain

There’s nothing to keep them together.

I knew none of this when I obsessively listened to the soundtrack, but hearing a song titled “Together” superimposed over “One” is a bit ironic, and something that two decades ago, I could’ve written an A-plus paper about. Now, thinking about my relationship with Gloria, the song, and my daughter, who six years ago was in the process of being born as I listened to “One” while timing contractions, I’m considering the nature of covers. What makes a good cover? What should a cover song do? As in: enact, or perform. According to Ray Padgett’s book on cover songs called Cover Me, musicians worried for years that if their song was covered successfully, that meant an erasure of their original. Padgett vehemently disagrees with that conclusion. For him, a cover expands the original, adds new textures and contexts, invites a new audience to enjoy the update and revisit the old. In other words, a successful cover only makes the original stronger.

It's just no good anymore since you went away.

She made herself known that balmy January day of 2022 not through sight, or sound, but smell. Warm jambalaya and cold, olive-stuffed muffulettas waited upstairs at Schoen & Son Funeral Home on Canal Street in New Orleans, where my mother and I would eat after we’d said goodbye to Gloria.

Though I didn’t speak at the memorial, I thought a lot about what I’d say. One of the things that made Gloria the best was that she was legitimately interested in what I thought, which stroked my ego in a way my busy mother couldn’t always do. But she was also interested in everyone else, too. There was some artistry, I suppose, in how she plumbed the depths of why people were the way they were. This is why she had so many conservative friends despite being one of the most politically liberal people I knew. Proof was all around me in the hundreds at the memorial, a great gathering of both the masked and unmasked.

The first to eulogize her was a young attorney, one of many for whom Gloria worked at the downtown law firm where she and my mother were legal secretaries for almost four decades. The attorney made a joke about the great unmasked, saying it was a testament to Gloria’s patience and grace that there were so many Trump supporters in the room. It reminded me that when Trump first came down that godforsaken escalator, right around the time Gloria was diagnosed with breast cancer (proof that if there’s a god, he’s a bastard), I raged and scoffed at the stupidity of anyone who could consider this monstrous moron as anything but a joke. Gloria reminded me that listening to others’ wrong-headed ideas only strengthens our positions, because we’re empathizing where they won’t.

Over a dozen people spoke beautifully at the memorial, including members of the great unmasked, but it was her college-aged niece whose impromptu speech most touched me. “I didn’t plan to say anything, but, my Aunt Gloria, there’s probably no other person as responsible for making me who I am as she was. She shared with me what was good, what was cool. Every piece of music I listen to or television I watch and love is because of her. I can’t imagine not being able to talk to her about any of it anymore.”

But silence touched me as well. During the parade of memorial speakers, I asked my mother if she wanted to say something, said I’d hold her hand and walk up there with her, if she liked. She just gently shook her head, and later, in the privacy of plating our jambalaya and muffulettas, said it’d been enough for her to tell Gloria’s family everything she felt, what losing her meant—losing the best friend she’d ever had, losing a piece of herself. In Gloria’s final days under home hospice care, Mom had been with her. She held her hand, watched her slowly go. She didn’t need to enact or perform her love.

One is a number divided by two

It’s sad, embarrassing really, how much I learned about Gloria from her obituary and memorial, simple facts I’d never bothered asking her about. Like me, she attended Nicholls State in Thibodaux, LA (a.k.a. Harvard on the Bayou), and graduated from LSU. How had we never discussed that? She was born earlier than I’d thought, in 1958, the same year, in fact, that Andy Williams swiped inside his cheek in the chorus of The Chordettes’ “Lollipop,” the very first sound I conjured when my water broke. The song “Lollipop” itself is a cover, first recorded by a long-forgotten duo named Ronald & Ruby. The oddly, wonderfully comparable sound would’ve never entered my mind upon my daughter’s arrival had it not been for The Chordettes and Andy Williams’ famous pop.

Covers are so ubiquitous now that we take for granted the term itself—why they’re called covers at all—and as stated in Padgett’s Cover Me, there are three theories for its derivation. The first is that a music label would “cover its bets” by releasing a recording of a popular song; in the second, the idea was that the new version would literally “cover up” the old on record store shelves; and the third, most capitalistic theory was how music label execs would answer, when asked if they had any copycat versions of a popular song to release: “we’ve got it covered!”

I can’t help but find a metaphor in these theories, and how they apply to the relationships I’ve held most dearly. Having a child is a way to cover your bets: if you can’t get everything you want out of this life, maybe your child can. Maybe they can cover up your shittiness, your aging, your (hopefully) slow bodily unraveling. If you choose to have children, a secret, sacred hope is that when you get old, they’ll care for you; they’ll have you covered.

Before deciding to have children, and still, I’ve been both afraid to be covered, and afraid not to be. I’ve feared motherhood would mean half-measures in artistry, and vice versa. And I’ve feared the obverse: that without motherhood, I’d have no excuse, no cover, for my mediocre art. But in listening to “One” again to write this essay, perhaps more obsessively than I did twenty years ago, after re-hearing the lament and singularity of being one, I see that although I planned to take Gloria’s path, and instead took my mother’s, the two paths weren’t discrete at all. The overlap lives in their love for each other. “One” can be sad, but “two” can be, too, and children won’t always cover our loneliness, or any other parts of us that need covering. This essay is an inadequate cover for the originality, the oneness, of Gloria. And of Aimee Mann. And of being a mother to my daughter and a daughter to my mother. But I’m making this cover, anyway. I’m still singing the song I’ve heard before, only singing it differently.

I’ve learned, too, that just the concept of covers is relatively modern. Before the advent of rock n’ roll, it was the song that was paramount, not the singer. The quality of the song mattered more than the person performing it. So to extend that cover-as-relationship metaphor, if my daughter is my cover, the question isn’t what she makes of me, or I of her; the singular song she makes of her life is what counts. My daughter, my cover, who first made herself known, truly, not through sight or sound or smell, but touch. After twelve hours of labor, when she crowned, then blinked, then screamed, I brought her to my breast, and tasted what it was for me to be born into someone irrevocably different, both alone and not alone, not joined together anymore, but not two, either, and never quite one again.

Brooke Champagne was born and raised in New Orleans, LA and now writes and teaches in Tuscaloosa at the University of Alabama. She was awarded the inaugural William Bradley Prize for the Essay for her piece “Exercises,“ which was published in The Normal School and listed as Notable in Best American Essays 2019, and was a finalist for the 2019 Lamar York Prize in Nonfiction for her essay “Bugginess.” Her writing has appeared widely in print and online journals, most recently in Under the Sun, Barrelhouse, and Hunger Mountain. She is seeking publication for her first collection of personal essays entitled Nola Face.