On The Importance of Not Knowing: Joshua Turner on concrete blonde’s “tomorrow wendy”

There is a line toward the end of Concrete Blonde’s Tomorrow, Wendy that resists quick comprehension. It’s the kind of moment that exists in a lot of songs, one you mostly don’t notice until you stop to think about it—the energy of the song carries you right past, and you sort of hum it indistinctly in your head without trying to decode precisely what the singer is saying.

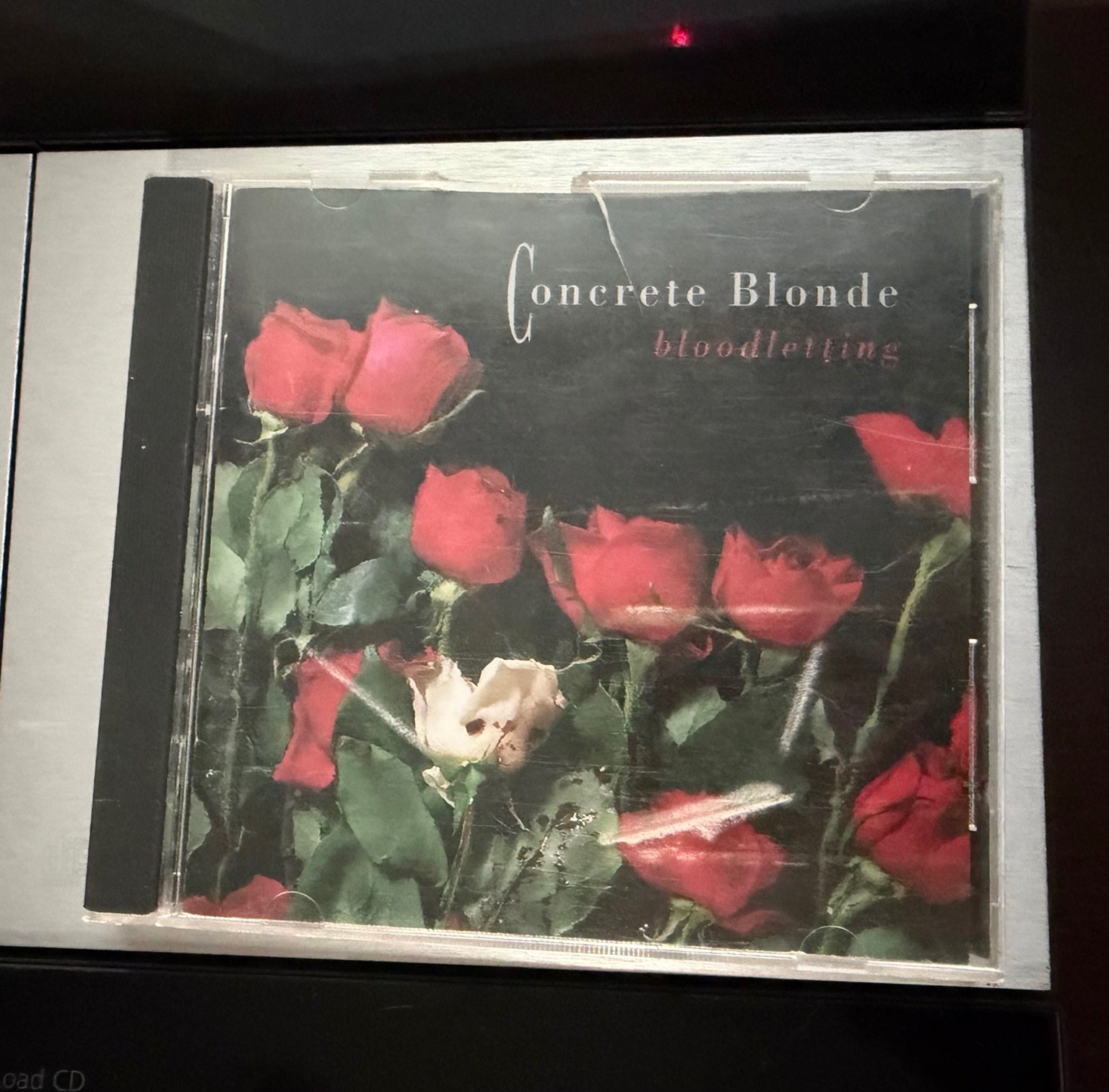

But sometimes you do notice it. And we did, a group of us, one night on a high school trip back in 1990. We didn’t have a portable CD player, so to play music in the hotel we’d brought a whole home stereo setup that we’d assembled and hooked up to a Kicker box from one of the cars. All of us had been listening to Bloodletting a bit obsessively that year; something about the vibe of the album, with its references to Anne Rice’s vampires and its smoky, bronzed vocals from frontwoman Johnette Napolitano, really captured the feel of the time. On that trip, though, my friend—let’s call him James, for this exercise—paused the disc and looked at us. What is she saying there?

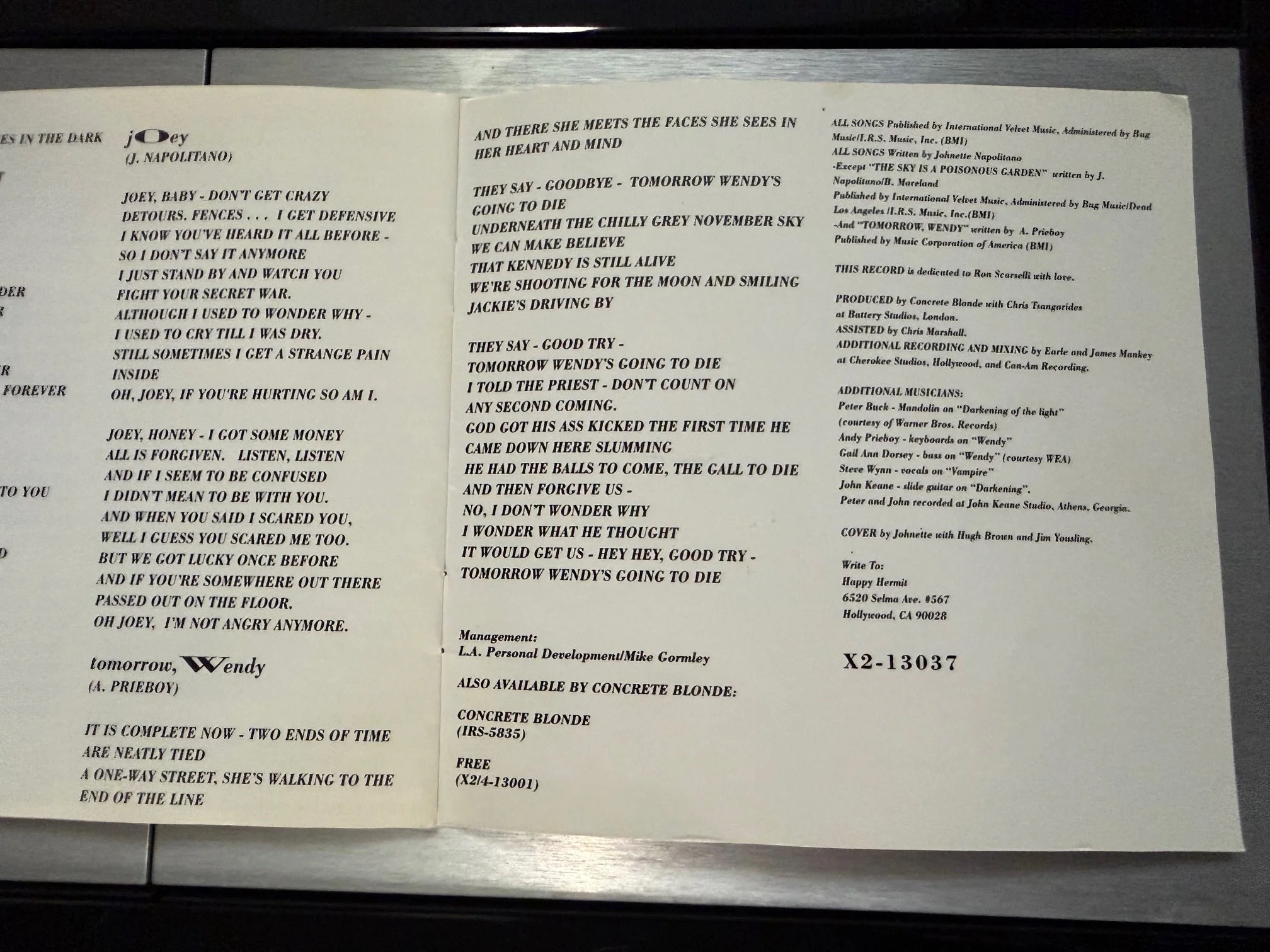

None of us knew. We threw out some ideas, but none of them seemed quite right. None of them really made sense. And when we pulled out the CD, the mystery deepened, because while Concrete Blonde had included a lyric sheet with the lyrics to Tomorrow, Wendy and all the other songs on the disc, the verse that held the unknown words—the final verse in the song, the last one on the disc—wasn’t in the printed lyrics.

So James decided to figure it out. For two hours, while everyone else went out, he put the disc on A-B repeat [1] and listened to that one lyrical snippet, over and over and over. When we got back to the room, he looked slightly manic and told us that at one point he thought he’d figured it out and then eventually the sounds had lost all semblance of meaning and he wasn’t even sure it was English anymore. But he gave us his best guess and we all agreed that, yeah, that seemed like what it was, even if it didn’t make much sense. Mystery mostly solved, I don’t think we talked about it again, but it has stuck with me ever since.

They Say Good Try

The Concrete Blonde version of Tomorrow, Wendy is the one that everybody knows, but it’s not actually the original—though to call it a “cover” is maybe also missing the mark. More of a sibling song, perhaps. The original was written and recorded by Andy Prieboy, a member of the punk/New Wave scene in San Francisco and Los Angeles in the early 80s who by that time was the frontman for Wall of Voodoo, joining after Stan Ridgway’s departure (and in the wake of that band’s big hit, Mexican Radio).

Prieboy has said that he wrote Tomorrow, Wendy about a woman he knew in Gary, Indiana, a prostitute and drug user who was diagnosed with AIDS and decided to take a fatal dose of heroin rather than succumb slowly to the disease that, at the time, seemed like a death sentence. The cold feeling of the industrial Midwest pervades the song, even if the location goes unmentioned in the lyrics. For that matter, the drugs and AIDS and the suicide are also not expressly conveyed, at least in the versions that have been recorded, but the increasingly bleak and enraged stanzas hint at the hopelessness of the song’s namesake.

In fact, according to Prieboy, Tomorrow, Wendy started as a very different song, one that he intended for Wall of Voodoo to perform. That would have been a 20 minute orchestration at a faster tempo, with each of the band members taking turns on the 27 different verses he had written. Understanding that Prieboy later made a comic musical about the life of Axl Rose called White Trash Wins Lotto probably helps contextualize what a 20 minute amped up rendition of Tomorrow, Wendy performed by Wall of Voodoo with “every guy [taking] a different character” might have been like.

Perhaps thankfully, Prieboy abandoned that frenetic vision in favor of something slower and more mournful, without the round-robin vocals. The recording Prieboy did make also features Concrete Blonde’s Napolitano, on backing vocals; the two were close, both living in Hollywood in the 80s. Prieboy’s version is arranged somewhat differently than the one that would become more famous, though not as differently as a Wall of Voodoo rock opera would have been. One interesting contrast with the Concrete Blonde version jumps out immediately, though. Napolitano repeats the phrase that would later bedevil us several times as part of the chorus, making it a fair bit easier to decipher. If we’d had Prieboy’s version, we probably wouldn’t have needed to spend hours listening to it—but then again, it likely wouldn’t have captured us, either. Listening to Prieboy’s original, you get the heartfelt emotion, but you can also hear why Napolitano needed to record her own.

So Concrete Blonde also recorded Tomorrow, Wendy, this time with Napolitano on lead, and in fact their version was released first, as the closing track to their third studio album. It’s certainly rare for a cover, if you can call it that, to be released first, but that isn’t why the Concrete Blonde version hit big and Prieboy’s cut remains mostly unknown except to music nerds and the dwindling universe of LA new wave devotees. Something like the Prince version of Nothing Compares 2 U, Prieboy’s performance of his own song ends up feeling like a demo, laying out a foundation for someone else to build on. Once Napolitano got ahold of it, she made it her own, and after you hear her sing it, it’s clear that was what the song always had to be. Indeed, even the songwriter seems to agree, saying that the moment he first heard Napolitano sing the chorus was “transformative,” and that it ranks as one of the ten moments he’d like to relive when he dies.

Tomorrow, Wendy also stands out from the rest of Bloodletting, which as an album dwells on possibilities and mysteries and roads not taken. In contrast, Tomorrow, Wendy, slowed down and opened up by Johnette Napolitano, is not a song about potential. It’s not really a song about mystery, either. It is a song about endings, and the soaring vocals contrast with the lyrics, which thud home with absolute finality.

There is nothing left to anticipate. Death may be the only true certain thing in life, but for most people even death reserves a surprise in its time and place of arrival. Not for Wendy. She has decided to remove even that uncertainty, to seize the one last bit of agency that an uncaring God has left her. The dirgelike cheer in the chorus serves as an inversion of joy, or maybe a perversion of it—hey hey, goodbye. Tomorrow, Wendy is going to die.

The glimmer of hope that does spark briefly in Tomorrow, Wendy is make believe, surreal, overtaken by events. At the end, under a chilly grey November sky, all that is left is to pretend that JFK is still alive and the moon landing lies in the future, not part of a past where the dreams of a young President end with an assassin’s gun and even extraplanetary travel grew boring and tiresome and was something we just stopped doing.

And it’s not just earthly hope that’s gone. It’s the hope for anything better. The song crescendos with a repudiation of even the possibility of salvation. In Wendy’s voice, Napolitano tells a priest:

Don’t count on any second coming

God got his ass kicked the first time he came down here slumming

He had the balls to come the gall to die and then forgive us

no I don’t wonder why, I wonder what he thought it would get us.

This is a cutting verse even today, but it’s easy to forget that in the late 80s and early 90s the Catholic church held greater sway in the monoculture, and blasphemy in popular art still had a legitimate power to shock. Scorcese’s Last Temptation of Christ, Madonna’s Like a Prayer, Sinead O’Connor’s stand on SNL against child abuse in Ireland by ripping up a picture of the Pope…all inspired protests and boycotts, and in O’Connor’s case arguably derailed her career. If the last verse of Tomorrow, Wendy isn’t on those same historical lists, it’s perhaps only because it never had the same pop culture reach, not because it wasn’t just as shocking.

A One Way Street

Back in 1990, we were seniors in high school, beset by the transitions that hit you then. We were all humming along that year, in a broader sense, trying to figure out the lyrics to our own songs and hoping no one would notice that we didn’t know them yet. My best guess took me to New Orleans, but not because the title track of Concrete Blonde’s Bloodletting album is set there, offering an Anne Rice-inspired gothic rumination on vampires by the warm, green river. Or maybe, if I’m being honest, not only because of that; it was all part of the charm and the mystery of a city I’d never spent much time in. Napolitano herself talks about being captivated by it, in her book Rough Sketches: “Being Californian, the South was mysterious and foreign to me, the huge silent cypress trees draped in moss, the little gaslamps flickering like fireflies glowing in the French Quarter.” Like almost everyone who goes to New Orleans, she leaves with a ghost story, a haunting in a hotel room—but what she really feels watching her are “unwritten words and music” that “hung in the fog, waiting to be manifested.”

It turns out, though, that my first guess about my own lyrics wasn’t right. For me, New Orleans didn’t end up being a place of occult mystery and creativity, but a city haunted by very real monsters from past and present, still trying to fend them off—or decide to succumb to them. It was a place where racism and resentment hadn’t been buried but had just been left out to rot and perhaps to rise, like the bodies in the swamp-filled cemeteries, floating up if you tried to push them too deep. Vampires were mysterious, romantic. David Duke was just an asshole, and gothic horror winds up being a lot more tolerable than the plain old human kind.

Eventually I figured out the right words, or at least a more plausible version of them, one that I could sing with a fair degree of confidence, and it involved going home and mostly starting over.

James’s guess at his words sent him to college in Arizona, but it seems like he also got them wrong. He was charismatic, a born leader, the kind of kid who had a beeper in high school not to deal but just so people could reach him. He was smart, but not so much interested in the academic part of school, and certainly not the academic part of college, so he wound up back home, too. We lost touch, in those days before the Internet made that impossible, but I would bump into him from time to time. He was trying different verses, working to make them fit. He became outdoorsy, bought a Jeep. Became an EMT.

But it seemed like none of that was ever quite right, either, and what had been fun high school and college dabbles with drugs appeared more frequent. And more serious. When Facebook came along, offering Gen X a 24-hour class reunion, we intersected again; by then, he had styled himself with a Buddhist title, looking for meaning there. It still seemed ill defined, uncertain, like he continued to be searching for words and just not being able to find them.

It wasn’t the biggest surprise a few years later when I heard that he died, in his 40s and still looking. Still uncertain, right until the uncertainty ended.

Johnette Napolitano doesn’t talk about Tomorrow, Wendy in either of her short books. She does talk about what it was like to scramble, to be young and a musician in LA, to do speed, and to tour. But she also talks about her brother, John [2], and getting the call she’d expected for years, even decades, when he died. Right around the same time as James, oddly. She tells the story of his struggles with trying to find himself, and says something about John that feels true of James, too: that he couldn’t keep up with himself anymore. Both of them, lost, never figuring out the lyrics to their songs.

Two Hands of Time, Neatly Tied

The Internet tells me that the mystery line in Tomorrow, Wendy is “only God says jump, so I set the time.” It takes less than a second to find that answer; the idea of sitting in front of a speaker for two hours, listening to the lyrics on repeat trying to suss them out, seems incredibly anachronistic, even more insane now than it did 30 plus years ago. If we’d had Genius or Wikipedia or Reddit back then, it would have been a momentary curiosity, a quick google, a slight “huh” as we tried to make sense of words that don’t fit easily with each other. And it would have been over nearly as soon as it started, curiosity sated, hardly the kind of thing that leads to lasting memory. Maybe in that world I’d still remember Tomorrow, Wendy fondly, but then again, maybe it would just be another one of thousands of songs heard over the years, sliding in and out of your life, leaving barely a trace.

This certainty comes easy, quick, with no real effort, depriving you of work that makes memories, shapes who you are, and gives you something to care about. It can also be illusory. Even putting aside the AI influence creeping across the Internet like a hallucinatory mist, it’s not clear how accurate these “certainties” are. Should you believe the lyrics sheet or your own ears? For example, the online lyrics for Matthew Sweet’s Get Older contain an apparent error that entirely changes the meaning of a key verse. Internet certainties are also only as good as the people who type them in…and how do they know? In August of 2025, Michael Stipe took to social media (Bluesky represent!) and revealed the “real” lyrics for It’s The End of the World as We Know It, a song that people apparently have just flat out gotten wrong in key ways over the years. It is “Left of west,” according to Stipe, not “Lech Walesa” or any of the other formulations drunk kids in bars belting along had guessed at. Of course, whether these are the actual real lyrics is also a bit of a mystery—as far back as the Green tour, I seem to remember Stipe confessing on stage that he didn’t remember them, most nights—and in a weird ouroboros moment, Stipe himself may have performed the song using lyrics he had printed off the Internet.

So maybe there isn’t as much certainty as we think. And maybe looking for certainty, settling for it, is a mistake. Maybe what you gain from certainty isn’t truth, or even convenience. It’s just an ending. Real certainty—true certainty—can only mean one thing: An end. An end of curiosity, of effort, of hope. Of possibility.

Maybe then what matters is still sitting down, letting the music play back to back to back, and trying to decipher the words and phrases for yourself, humming along until you think you know it, always a little unsure. There’s risk there—risk you’ll get it wrong, risk you’ll never find the answer, risk that you’ll always be lost, that like John and James the music will stop before you can decipher the lyrics.

But there’s also possibility. Hope. The ever-present chance that you will figure it out, or at least some version of it. The uncertainty means things can get better. And maybe you’ll realize you can be happy, because you don’t know what happens tomorrow.

NOTES

[1] This was something old CD players could do, loop one part of a CD over and over again, and I could never figure out a use case for it, other than this exact scenario.

[2] The names—Johnette for the first born daughter, John for the son—were not a coincidence; as she tells it, she was supposed to be John, and surprised her parents at birth by being a girl. Undeterred, they tried again.

Joshua Turner grew up in suburban Detroit doing preemptive Harry Potter cosplay and, like a lot of suburban kids, got into Concrete Blonde partly because of Christian Slater’s pirate radio hero in the movie Pump Up the Volume. Josh is now a communications lawyer in Washington, D.C., and thus wants to remind you not to violate the Communications Act by becoming a pirate radio DJ. This is his first essay on music.