(16) stereo mcs, "Connected" defeats (16) billy ray cyrus, "achy breaky heart" 56-54 and will play (1) los del rio, macarena in the first round 3/1-8

Read the essays, watch the videos, listen to the songs, feel free to argue below in the comments or tweet at us, and consider. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchfadness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on Feb 24.

voting widget goes here

laura c. j. owen on "achy breaky heart"

In this brave new world, under the order of a President obsessed with winners and losers, it’s comforting to know that there’s one contest I’ll always, always win: the who-has-the-worst-one game of What was your first concert?

While the rules are never laid out explicitly, this first-concert conversation always becomes a game of oneupmanship about whose first concert was more embarrassing. It depends on the generation, of course, but within my more-or-less-contemporaries a lot of boy bands are usually represented: New Kids on the Block, the Backstreet Boys.

Sometimes, it’s an embarrassing admission baked into a humblebrag: I went to an Eagles concert with my mom cause we didn’t listen to anything recorded after 1980 in my house. Translation: I was uncool but not, like, trendy.

I wait until everyone’s finished chuckling at their younger selves, and then I win, number one with a mullet: my first concert was to see Billy Ray Cyrus.

“Achy Breaky Heart” is a great fucking song. It’s catchy as hell, guitar-y and synth-y, and shot through a wry melancholy, a broken-hearted persona ironically distancing themselves from their own heartbreak. Slow it down, make it more self-consciously ironic, give it a queer twist, and it’s a Magnetic Fields song.

I just liked the stupid song. When I was ten years old, it seemed like a safe place to land: popular, recognizable, no SEX REFERENCES that I didn’t understand that would later turn out to be minefields if brought up on the playground (“you do know what that means, don’t you?”).

“What music do you like?” is in and of itself a minefield of a question, and at around age 10 I began to appreciate this. I could no longer slide along on the music my parents liked—it wasn’t enough, anymore, to claim to like The Rolling Stones or the Beatles because my dad liked them: Adults would be impressed, sure, but others kids didn’t give a shit. “The Beatles and the Rolling Stones aren’t really bands anyone cares about anymore,” my fifth grade teacher said. Even the adults were on to me.

So you had to say you liked something new, something popular, and something uncontroversial—no Madonna, for instance, because of SEX REFERENCES.

In 1993, in fifth grade, in Tucson, Arizona, “Achy Breaky Heart” fit the bill. That was what I liked. That was the song I liked. That would do. Everyone liked something, and so that was what I liked. Okay? I liked “Achy Breaky Heart.” That was the song that I liked. Billy Ray Cyrus sang the song, so I liked him, too. Probably.

Yet it wasn’t enough, I began to realize, to like “Achy Breaky Heart” because it was catchy and about self-pity (two qualities I’d later learn to identity as selling points in music for me). For starters, “Achy Breaky Heart” was on a cassette tape of other Billy Ray Cyrus songs and it became expected of me that if I liked Billy Ray Cyrus, that I own the cassette tape.

The cassette tape wasn’t great. Aside from “Achy Breaky Heart”, the only other okay song was “Some Gave All,” a song that made use of the literary device of antimetabole to make a Statement about the Vietnam War. “Some gave All,” sang Billy Ray, “but All gave Some.”

Then there was a Billy Ray Cyrus television concert special on TV, which, when it was brought to my attention, I had to watch because now Billy Ray Cyrus was the music I liked. So I watched Billy Ray Cyrus’ television special, live, on our living room TV, flanked by my parents. They didn’t like the music, that was clear, but somehow it was important to them anyway, to let me watch it—because now I was my own person, with my own music, that I liked.

“I bet if Billy Ray Cyrus comes to town, you’ll make us take you to see him,” said my mom.

I once opened a fortune cookie that read “If it seems like the fates are aligned against you, they probably are.” So it was that day, when mere moments after my mother spoke, an ad appeared on our TV, announcing Billy Ray Cyrus’s tour stop to Tucson.

We were trapped. I didn’t really want to see Billy Ray Cyrus in concert. My mom didn’t really want to take me. I was fucking sick of Billy Ray. I’d heard “Achy Breaky Heart” a million fucking times at this point. I didn’t give a shit about “Some Gave All” or Billy Ray’s mullet or his concerts. But if you liked music, you liked concerts, right? That’s what liking music meant, right?

So I pretended. I pretended I really wanted to go. And my mom was trapped because she’d just made a whole thing about it.

So it was just me and my mom that went to go see Billy Ray, just us two—because if you’ve been paying attention to context clues, you’ve realized that I didn’t have any friends, and this was, I think, the real source of my parents' anxious anxiety around indulging my interest in Billy Ray Cyrus. They wanted to be reassured that I liked normal kid stuff and was being a normal kid and that’s what you did with your normal kid, indulge their interest in music you didn’t necessarily like because oh, kids!

But I didn’t really have my own friends or my own interests, even though I pretended that I did. A neighbor kid next door was obsessed with New Kids on the Block, and I nodded and smiled and said, Oh cool! to her New Kids on the Block bedsheets. Clearly, that was what you did to be a normal kid: you liked a band, and so that meant you wanted to go to their concerts and sleep on their faces. It was a whole thing. So I needed to like a band, and there were no Billy Ray Cyrus bedsheets, and so my mom and I went to a Billy Ray Cyrus concert.

The video for “Achy Breaky Heart” gives you a good sense of what a Billy Ray Cyrus concert was like. Watching it now, I had a vivid flashback: oh god, the line dancing. They all did the line dancing.

My mom and I watched from our nosebleed seats, from which we could observe the bulk of the crowd. In addition to the line dancing, the whole concert was based around a singular narrative line: would Billy Ray Cyrus take his shirt off?

The crowd begged and pleaded. They yelled and howled. Briefly, they were distracted by line dancing. But it always came back to the same imperative: the shirt, the shirt, take off your shirt!

He obliged, eventually, although a thin wife-beater remained underneath, a clear cheat of the system, registered in the crowd’s restive mutterings.

After the climatic shirt-taking-off moment, he solemnly sang “Some Gave All,” and the crowd was shamed into briefly shutting up about the shirt situation.

The whole thing was orchestrated down to the moment. Years later, his daughter Miley Cyrus was both celebrated and shamed for her willingness to get skimpy publicly—memes emerged online of Billy Ray Cyrus gazing down from her above, The Lion King style, as if to register his disapproval. To which I say: the Cyrus family does not owe its fame to Miley getting topless, and we would do well to remember that.

It became clear to me, up in that auditorium, 10 years old, up way past my bedtime and longing for death, that liking music was complicated. It entailed albums, and album cover art, and concerts, and mullets, and stripteases and earnest positions on the Vietnam war. You couldn’t just like one song, one song that was impressively both catchy and sad, and so that’s why you liked it. What kind of music do you like? meant Who are you as a person, economically, spiritually, sexually, and socially? and I had no idea. Cleary I wasn’t a line-dancing, woo-wooing, take off your shiiiiiirrrrrrrrt!-type Billy Ray Cyrus fan, though I was jealous of them, because they were having a great time at this concert, while I was miserable. I had misjudged everything, everything, that liking a Billy Ray Cyrus song meant; I had made a catastrophic misjudgment about What I Liked, and thus Who I Was.

When people ask, What kind of music do you like? They are not just asking what you think is catchy, what you hum along to in the car, what you heard at age 10, what’s fun to you, what your parents liked, that one song that was kinda good. It means What are your values? What do you think beauty is? What economic and cultural groups do you identity with? What is your stance on mullets? This is why What music do you listen to? is such a dangerous question on first dates.

“What bands have you been listening to lately?” I overheard a man ask his date at a coffee shop recently.

“I haven’t really been listening to any bands lately,” she answered, deflecting the question in a wary way that was itself telling, like, I’m spiritual but not religious or I’m just too busy to follow politics.

Still, I felt some sympathy with her non-answer. We’re not all ready to get so intimate on the first date. And there’s no way What bands have you been listening to? isn’t a test, to which there are definite, definitively right and wrong answers. As it was in fifth grade, so it is forever.

What music do you like? is so fraught because humans are contradictory creatures. This captured pretty well within the lyrics of “Achy Breaky Heart”, in which different parts of the body are personified, each with their own distinct personality, with an unreliable umbrella narrator trying desperately to corral them all together:

Or you can tell me eyes

To watch out for my mind

It might be walking out on me today…

Parts of me can be trusted, the song suggests: my eyes, my lips, my arms, my legs. But then, some parts of me just can’t bear to hear the truth: my brain, my ol’ achy breaky heart. Most of me is okay: parts of me aren’t. Do I contradict myself? sings Billy Ray Cyrus: I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitudes.

This kind of personification has been evoked recently by the popular online Awkward Yeti cartoons in which the sensible-but-neurotic Brain is in constantly odd-couple battle with the whimsical, vulnerable Heart. I love this song, Heart instructs Brain, Play it until I hate music. Heart never envisions a world when it might get sick of a catchy number, where the passions of today quickly turn into the cringe of tomorrow. Don’t tell Heart you’ll one day get sick of that song, be embarrassed you ever went to that concert. To Heart, liking music isn’t an identity contract, a social position, a commitment to an artist’s touring schedule, or a reasoned presentation of self. It’s the push of a pleasure button.

Billy Ray’s career has taken some strange turns since “Achy Breaky Heart”. He was in a David Lynch movie, who cast him after listening to his music. Despite some country music success and quite a few acting gigs, in the world of pop music he’s forever Miley Cyrus’ dad and the Achy Breaky Heart guy.

But that’s what’s glorious: “Achy Breaky Heart” now belongs to everyone and to no one. The beauty of fads and one-hits wonders is that they don’t commit you to any musical philosophy, to any particular point of view, to any ride-or-die fandom.

“Achy Breaky Heart” is now freed from the 1993 baggage of being a Billy Ray Cyrus Fan, trademark (members must learn the line dance, buy the cassette, practice the sexual harassment). “Achy Breaky Heart” can now and always be what it is: a sad and surreal little number, as catchy as it is complicated, somehow corny and tongue-in-cheek, danceable and blue, full of twang and snap, a song I want to listen to until I hate music.

Laura CJ Owen is a writer living in Tucson, Arizona.

steve wasserman on "connected"

“Each angled to its point of flux & so on & with so much its place removed, the leakage in moral sense to the “error signal”, making the rainfall restless, unstable: the loop not connected but open & induced to nothing.” J.H.Prynne, “Air (iap Song”

“Somethin’ ain’t right. Gonna get myself, I’m gonna get myself, gonna get myself connected.” Stereo MC’s, “Connected”

Get Yourself Connected #1: “The writing’s on the wall”

A WH Smith newsagent window, Market Street, Cambridge, October 1992. Dissociated-me shoving a Cranks’ Date Slice into my gob, registering but not taking note of the over-saturated colours of this poster advertising an album that has not been branded in any way for my affinities: volcanic eruptions! psychedelic mushrooms! snakes! lubricious orchards and passion flowers! extra-terrestrial transmissions! the band as shamanic explorers pushing through the dubfunkacidtriphop undergrowth, whilst sampling/stealing hooks from more likeable, effortlessly groovy indigenes.

A few months after releasing Connected, the Stereo MC’s would flog both it and the instrumental B-Side (Disconnected) to Carphone Warehouse. The Warehouse, founded the same year I started university (1989), was soon to become one of the largest mobile phone retailers in the UK.

Referring to themselves as ‘Communication Centres’, they would use Connected and Disconnected for a decade or more as the stomping sonic backdrop to their incessant shlock-and-bore advertising, so that the memory of the song is now almost entirely blistered over with irritation and aggravation.

Maybe you’d be watching The X-Files, or Frasier, or Friends, or The Big Breakfast Show, no matter. Wherever you’d be getting your primetime fix, the motivational neurocircuitry of your brain would also be getting “connected”, dosed up every ten minutes or so with the prescient message that virtual association via mobile telephony and this thing we now call the internet was going to be the answer to your most fervent prayers and fantasies.

Something ain’t right? Existential dread and ire? Gotta get yourself, you gotta get yourself gotta get yourself connected, bruv!

GYC #2: “If your mind’s neglected, stumble you might fall.”

It soon became clear to me, even by Christmas 1989, that I was not clever enough or sophisticated enough to maintain the kind of conversational connections that fuelled the intellectual and social life of Cambridge, so I disengaged, bypassing opportunities for affiliation, tucking myself away.

Rather than go to Hall each evening where my cohorts, begowned in their navy blue academic robes with black velvet trim, sparkled and shone with Brideshead Revisited wit and banter, I would eat my main meal of the day at an Indian restaurant, a fifteen minute walk from the University Library which usually shut its stacks at 7.15 pm.

I was particularly fond of the vegetable Jalfrezi, but usually limited myself to a side-dish, a Saag Chana or a Tarka Daal with some basmati rice. I liked the restaurant because it was as disconnected from the grandeur of the University and its social expectations as I could possibly find.

Once I became a regular there, they would often give me a vegetable samosa or garlic naan for free. It was perfectly OK to sit and read my book as I ate my meal, no obligation whatsoever to engage “in wide-ranging, interdisciplinary conversation, with protocols promoting maximum civility…which can be educative at the time as well as lead to further networking beyond the confines of the occasion” (notes on Formal Hall from my college prospectus).

How far through this world could I go without exchanging a spoken word? Without any force, just not actually speaking when you didn’t need to? My record was two and a half weeks. This mealtime routine was one way of dispensing with the pressure to talk, to perform a self for which I had had no prior training up to this point.

So Lent, Easter, and the following Michaelmas Term passed with me living an intensely isolated life, increasingly aware that the profound joy and meaning I usually found in reading and writing (“You’re good at this sort of thing, have you ever thought about applying to Cambridge?”) was progressively being drained away, until finally I stumbled and fell.

GYC #3: “Ya dirty tricks, ya make me sick”

That we seek and need to be connected goes without saying, but is connection an end in itself or is the push towards gratification through other people the means to that end?

We don’t like to think of ourselves as inherently selfish which is why a narrative of relational reciprocity (connection for connection’s sake) now dominates the discourse in most fields. But perhaps President Trump and those for whom he speaks and rules might be asking us to revisit an older, Freudian narrative?

In this Connected/Disconnected Story, we begin with some kind of bodily tension, a libidinal impulse for food, sex, or the latest Netflix offering. This then gets converted into an aim or setting (a supermarket, Tinder, or streaming media), where we might look for as well as serendipitously find the object of our desires.

Add to this a set of elaborate defence mechanism to keep more socially unacceptable drives repressed or diverted into harmless activities like writing cultural critiques or watching music videos on YouTube, and you’ve got the transformation of neurotic misery into the more bearable state of everyday unhappiness.

Melanie Klein, the psychoanalytic Mama of the Connected/Disconnected fairytale goes one step further, by splitting off the connective drive and our disconnected resistance into two separate containers: good breast and bad breast. Or in the parlance of popular culture: good cop/bad cop. Or as political ideologies: Hilary and The Donald (if you’re a Trump supporter: The Donald/Hilary).

If connection to the object (person, song, piece of writing) releases our libidinal buildup, we are rewarded with the happy life-sustaining sensation of gushing nutritious goodness. However the same object, or some variant of, can just as quickly flip to a deprecatory position, where our empty bellies and aching needs become projectively identified with the Bad Breast, against which we might hold some pretty intense and destructive retaliatory fantasies.

“Ya dirty tricks, ya make me sick,” howls Psychic Baba at Bad Breast, gnashing down on its impervious nipple. A minute later, spotting Good Breast hoving into view, oblivious to the fact that both offer ways of connecting to a caregiver, he turns away from the “Bad” to the so-felt “Good”, humming all the while: “Gonna get myself, I’m gonna get myself, gonna get myself connected.” [Slurp].

GYC #4: “I see through ya, I see through ya.”

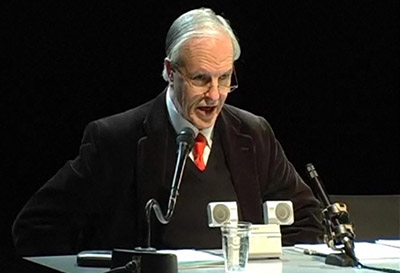

I’d now like to say something about Jeremy Prynne’s breasts. Jeremy Halvard Prynne, described by the Paris Review last year as “the mage of the Cambridge School”, but also, in 1993, the Director of Studies at my college. Prynne having thus played an important role in the connective matrix of my academic psyche, a double-breasted Attachment Figure of sorts.

In my drop-out year, I’d pushed myself to read more of the people he liked and admired (Olson, O’Hara, Dorn, Wordsworth, Celan) thinking I might try and write a kind PoMo mash-up so as to make up for being a negligible presence in the two years preceding my stumble and fall.

This began as a little chapbook called More Games For The Super-Intelligent, the poems emerging from the detritus of all my lecture and reading-for-essay notes that I had spent the last three years accumulating in what seemed to be depressing, and increasingly useless quantities. Working in this way, I could somehow deflect the input of personal preoccupation so that the interior of the poems was sometimes interchangeably positioned with the exterior, there being at some point no clear arbitrated priority between those aspects.

I presented the manuscript of More Games for The Super-Intelligent to the most intelligent person I knew (Prynne), the chapbook at this point serving the multi-media purpose of a script for a play that clearly needed to be performed. The other day I googled the names of the three people who performed More Games with me on 15-20 February 1993 at the Cambridge Playroom (Eva Czech, Dallas Windsor, Natasha Yarker), and not a single LinkedIn or Facebook profile could I find. Was the whole thing a psychotic episode, the poems, the play, me studying at that university in the first place?

Prynne read the poems and in his somewhat mannered and formal way was very kind and generous with his comments. I asked if I could get a discount on photocopying 100 copies to give away at the performances the following month and he suggested I use his non-carded photocopier in the librarian’s office, coming down to open up for me at midnight. I also photocopied a number of A3 posters of myself as Vitruvian Man, the thought of which now fill me with horror. It was the same image used on the cover, a gaudy self-indulgent Gesamkunstwerk in a desperate bid for connection through the warped lens of indecent exposure.

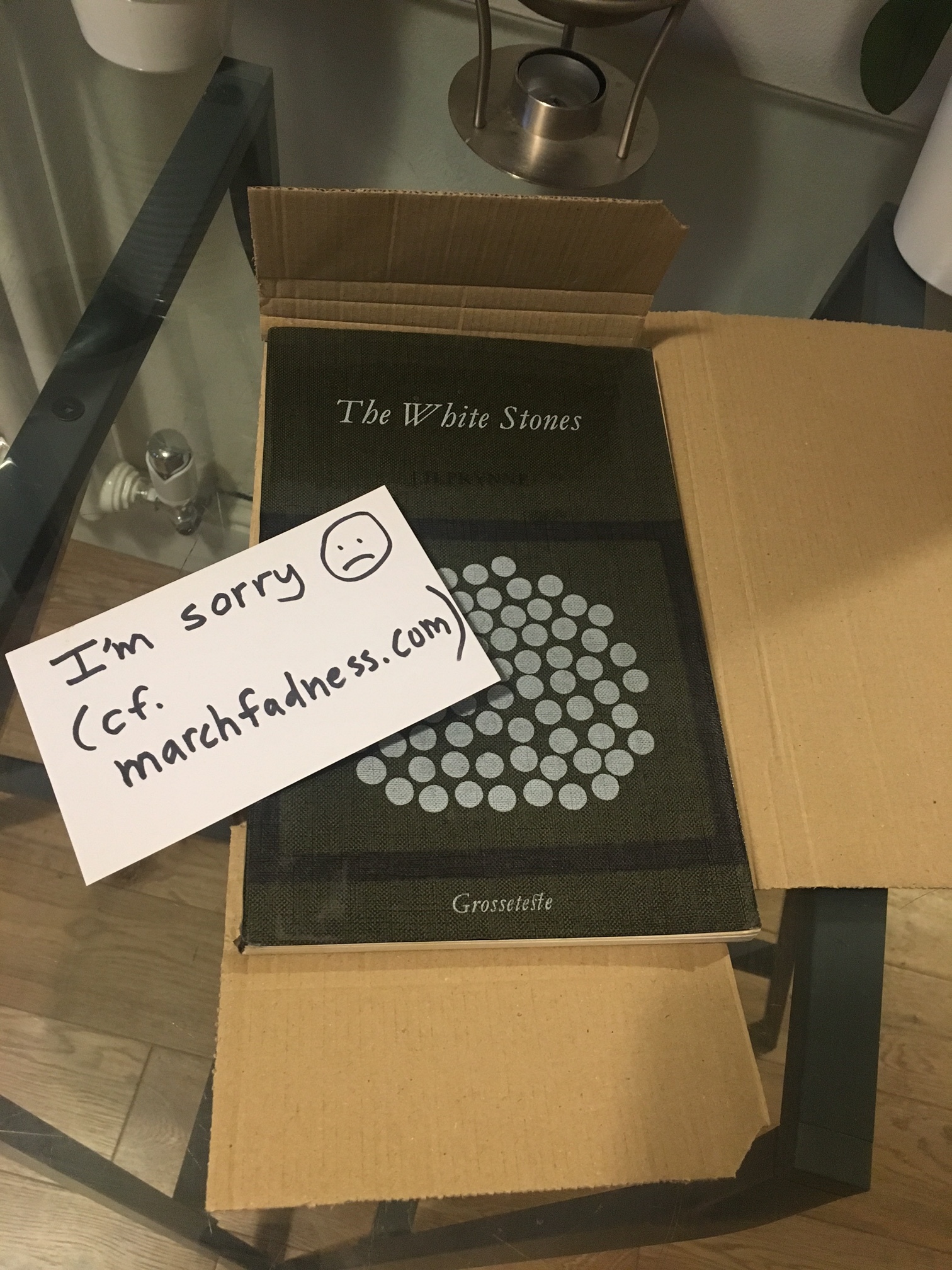

How did I repay Mr Prynne’s kindness? For starters, by stealing a valuable first edition of White Stones from his library (not on the night itself, but later), the college library, which he presided over as part of his duties in a Mother Hen kind of way. But worse than that as far as propagating shame, I then spent the next 25 years selectively remembering Prynne not as a mage but a Wizard of Oz, a kind of impenetrable and frustrating twit.

How in my imagination had he become so lopsidely Bad Breast? What was the empty belly frustration about: his shyness and obtuseness? The resistance and difficulty of his own position? This position was put forwards as a kind of manifesto in an essay Prynne penned his early 20s, an essay describing how the reality of the external world can’t help but be predicated on the resistance it offers to our awareness. “The stone’s hard palpable weight is the closest I can come to the fact of its existence,” he writes, ”and the reserve or disagreement of my neighbour is my primary evidence for his being really there.”

GYC #5: “Ya terrified (I wanna do it again)”

Toffs and Toughs, Jimmy Sime (1937)

“Humiliation,” writes Wayne Koestenbaum, like other educating experiences, “breeds identity”. He cites Jayne Eyre, whose identity as “unlovable outcast” evolves in response to being locked in a red room for stealing a book that she too cares little for, utilising it as a kind of shield-cum-escape-hatch against the dreary November day and her punitive guardians, the Reed family. “Humiliation isn’t merely the basement of a personality,” notes Koestenbaum, “or the scum pile on a stairway down. Humiliation is the earlier event that paves the way for self to know it exists.”

I think he’s right, although I would rephrase that last sentence by saying that humiliation paves the way for “a self” to know it exists: more specifically the besmirched, exposed, shamed self, a self that all of us spend a good amount of time either repressing or covering up, deflecting and sublimating through other selves. Selves that have socially valued skills (I’m a psychotherapist), selves broadcasting their affiliations to groups they want to be included in (“Can I write an essay for your literary magazine?”), selves trying to connect with more powerful selves through the language of “Liking” and “Replying”, a game of Impression Management that make the Carphone Warehouse TV and radio ads of the 90s now look like child’s play.

I wonder how the Stereo MC’s deal with their tainted selves when the Carphone Warehouse jibes start piling on? Or maybe they’re no longer a trigger for shame, maybe the MC’s did good things for themselves and others with their advertising moolah?

Maybe for them, the shamed self is more liable to pop up like a weed from the soil of humiliation when critics lay into their follow-up efforts with the sadistic glee of Bronte’s truculent John Reed or the castigating clergyman Brocklehurst. “Generic self-help guff,” carps Reed (aka The Guardian’s Dorian Lynskey). “An uninspired stew of stale ideas and careless execution” moans Brocklehurst (aka fellow music critic/gravedigger Peter Petridis).

I can try and neutralise some of my own University shame and humiliation by sending that stolen copy of White Stones back to Gonville and Caius Library, or by writing about the oftentimes puzzling and worrying antics of my younger self as I have done here. But how does one finally lay to rest and meaningfully disconnect from the chiding chatter broadcast forevermore on that exterior searchable channel called Google, as well as the interior associatively connected circuits of memory, the inner-net?

The other day I asked a colleague to EMDR-me-up whilst I sat and read aloud from this text. This involved her, after each segment, waving her fingers back and forth about ten inches from my face, so generating bilateral eye movement, checking in occasionally with my humiliation appraisals via a Subjective Unit of Disturbance Scale. Describing and visualising my naked self on that photocopied cover of More Games For The Super-Intelligent gave me an initial SUD rating of about a 9 (out of 10). We got it down to 6.5.

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing as kooky as it looks and sounds is a well-respected treatment for meliorating traumatic memories. A more ancient treatment comes in the form of writing essays, short stories, poems, and maybe even slightly naff songs like those on the March Fadness roster. The academy of course frowns on writing-as-therapy, but in the words of Mr Robert Birch and Mr Nick Hallam, Stereo MC’s, “I ain’t gonna go blind for the light that is reflected. Hear me out, do it again, do it again, do it again, do it again, I wanna do it again, I wanna do it again.”

Steve Wasserman works as a psychotherapist in London. Currently connecting via Read Me Something You Love (a read-aloud, short story/essay podcast) and Gardening/Life (a blog). Twitter: @stevewasserman_