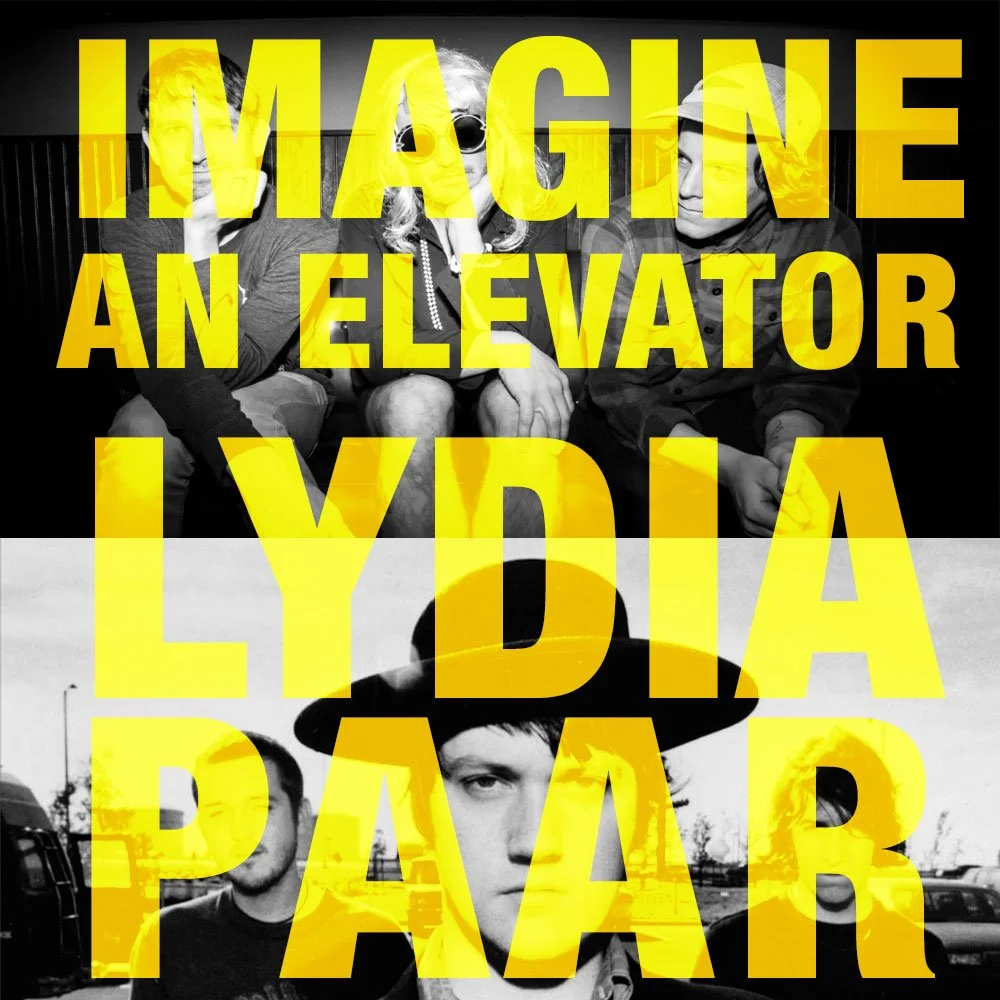

Imagine an Elevator: Lydia Paar on portland, modest mouse, strfkr, and getting too old to go to late shows

When the summer in Tucson gets like this—the beautiful oven you thought had maybe worn itself out in June, but then the monsoons didn’t quite come to fruition so now August is also ablaze–you find respite in memories of cooler times and places.

To be certain, your old hippy hometown, Portland Oregon, shaped up into “hip” and overblown in the media these past two decades, has real estate prices reflecting its coolness, and people tend to wash over its flaws as they, too, are washed by its incessant drizzle, but ah…Portland in the summer really was true pleasure. Yes, you took it for granted! Why didn’t you get a cheap bottle of vitamin D and enjoy the fact that you could walk everywhere: so what if your feet and ankles never dried?

Here, now, as a 40-something, you care about climate change, real estate prices, hormones, and you’re trying to fight fascism with something akin to Flower Power. You stuff earplugs into your ears during office construction at the job that almost eats your life each semester, and you spend too much time contemplating how to make your workplace less toxic without getting fired.

When you were 18, 20, 23 though, you were concerned mainly with ingesting and inscribing every element of the world outside your grandma’s attic, your bedroom, into your intelligence: traveling. Books. Meeting those people who wrote and made music and danced. Anthony Bourdain, a sassy and sensory writer born from his time as a chef, became your beacon that the working class, your class, could work hard, play hard, express their experiences and be heard (and you could eat well, meanwhile). You had an older boyfriend who hooked you, not on dope, but on music as emotional strategy. To understand chaos. To learn who you were in the face of it.

So you went to all the shows you could: Sleater Kinney, The Dandy Warhols, Le Tigre, and a bunch of other smalltime groups whose names escape you now. Your favorite band was fast becoming Modest Mouse, even before you learned the name of the band came from a Virginia Woolf quote about the “modest mouse-coloured people, who believe genuinely that they dislike to hear their own praises” still secretly liking to be praised. You liked the band best because the working-class-fashioned frontman Isaac Brock was self-admittedly not well educated and yet he wrote earnest, razor sharp poetry-songs about the sad shit of living in the late 90s and then the artifice that came with 00s, and then sometimes (later on at least) the fragments of hope that he saw in all this shit, but it was never corny. There was no romance sans destruction, no pleasure minus work; and hypocrisy, and irony, two feelings which, for a high-schooler who always worked slavish service industry jobs while your classmates went to sports events and fancy family vacations, resonated. You felt that Brock, too, had stood on the edge of eating versus not, having housing versus not, had done all these crap jobs too, and yet still chose poetry over moving up through middle management at a mini-mart chain.

So you went to some shows and sang along with the lyrics you’d listened to too many times on a knockoff sony discman and the crowds felt the same exhilerated and sometimes irritated inspiration.

One day someone yell-asked if you wanted to be lifted onto the top of a mosh pit to crowd surf—you were tiny at the time—and you nodded, starting to hyperventilate while the strong plaid-clad arms of two strangers eased you up.

Then you floated on a pillow of anonymous hands, which somehow acted carefully as one support structure to ferry you around and then put you gently down. You lost your wallet, but you didn’t know it until it showed up in your mailbox the next morning with a nice note from a fellow mosher-turned-wallet-returner, who invited you to visit Scotland someday.

You met Josh at a similar kind of charmed event downtown: not a show, but a lesser-known dance club that played actually great canned tunes. You’d actually never known a whole group of people to decide to get together and “go dancing” up to this point (this would have been far too hip for your stuck-in-grunge high-school pals), but a new post-school friend from a new whiter-collar job at a shi-shi downtown lawfirm had this updated, creative posse and that’s what they were gonna do, no band necessary.

Was it possible your lawfirm friend was trying to hook you up with Josh?

“He’s in a band,” she said, and it sounded a little like selling him.

Band = a group of people, a community. Whether there’s music or talent involved, perhaps the “part-of-something-bigger” appeal?

You’re not sure why she was alluding to him getting expelled, maybe, from your high school. Does the bad boy still appeal? The flawed but fixable creative?

When you met him, Josh was totally nice but your attention was distracted by another neon-seeming man that night, so you and Josh remained just friendly social acquaintances. One New Year’s Eve evening you and Mina, the only girl from high school you took with you into the Great Beyond, didn’t have anything to do, so instead of going out drinking you went to his friend’s house and played the Apples to Apples combination word game. This was before the cruder Cards Against Humanity came out, but Josh still played a winning card combo that somehow made a joke about looking on the bright side about HIV = making “LemonAIDS! Get it??”

Fast forward a year: you wanted some bands to play in your basement for your goodbye-to-Portland party because your gramma, whose basement it really was, was gone.

And a law career seemed SO stale.

And you’d decided to finally see the world…starting with Arizona?

…At which time you invited him to play and he came over to check out the arrangement: where he’d plug in, put the drums, etc.

Then you sat on the back steps and chatted, and he told you he was a security guard at the moment, but hoped to quit.

And that he might change the band around, rename it from Sexton Blake to Starfucker.

He’d had to quit drinking, because, indeed, he’d been expelled from your high school. But he didn’t want a day job at all: just wanted to make music all day.

And you liked his music as much as his life mission, a sometimes dreamy and sometimes dreary take on urban synth pop: overbright, plucky keys, whispery lyrics, a rhythm as steady and droning as if someone thought they might go dancing but then took Benadryl.

The band’s rendition of Elliot Smith’s “Rose Parade,” in the middle of which Josh forgets some of the words and calls himself on it mid-song, embodied the semi-depressed and self-deprecating kind of funny so many Portlanders have known and embraced since the 90s alongside the off-key/grating/complaining Decemberists’ semi-klezmered sarcasm. Alongside The Shins' secret envelopes of bittersweet. And the king: our somber and no-longer-Sisyphian Elliot.

The love you had for these bands was so tender and so loyal. The emotional strategy they helped you to develop was guided by amalgamations of sound, surprises and twists in the lyrics just clever enough to keep your mind at work against the gloomy sense of expectation: that Portland had potential to bloom, lead the national culture into some new and foreign intellectual territories, but maybe in the spring, because no one wants to go outside for the long seven-or-so months of winter.

So you never really thought these bands (or their strange poetry) would make it out of Portland: the town was full of talent and eager supporters but America moved mostly faster. But Elliot Smith was dead now. Sleater-Kinney split. Lots of local band members OD’d, sobered up, babied up, or got straight jobs. Isaac Brock was so brilliant as guitar-holding poet and half-tuned chord-bending savant, but he had always been too drunk. It’s fine, you thought. If common cultural memory leaves all these people and their talent and their dreams only in the memories of a handful, so be it. Most of us end up that way. This moment mattered anyway.

Then one day, gliding across Seattle’s Capitol Hill in someone else’s car, either right before you moved or on a visit from Arizona, there was Modest Mouse again, that strangely cheery “Float On” song that pissed off all their crustiest middle-aged male fans, blaring out from someplace new: the radio! And not the local station.

“Sellouts!” the crusty (former) fans screamed online.

“They’ve made it,” you exclaimed to Mina.

You were alone in Target (buying socks?) not long later in Flagstaff, Arizona when you heard STRFKR, spelling now compressed to confound FCC rules, on the store’s overhead muzak system, and you had no one to exclaim to, except a couple of confused and random red-shirted sales associates.

So you bought tickets to see them when they came through town and reconnected. Josh had moved the band to LA. He and a friend of yours met at a party you invited him to and they dated for awhile. Then the world turned and he moved on and eventually you moved too, to tougher cities, hotter and sweatier and grittier.

STRFKR continues to tour. Josh will (unless some things go really wrong) never have to do security work again. Neither will the members of Modest Mouse, who also tour, in multiple big buses that clog city streets around their venue.

You’d love to do some wordplay here with their lyrics to demo this collective brilliance and hot joy, but their big record labels might sue you now, so nevermind.

It’s so nice when some people make it. Especially sensitive, humane, creative ones. And you wish you could end the “slice-of-life, moment-in-time vignette right here, where things sometimes work out.

But that would be unfair to the present, where fewer things feel like they’re working out, where it seems some of the charm of one era (in an era that did not, vehemently did not, view itself as charmed), has leaked away for good.

It’s now summer 2025.

Local desert slow-rock heroes Calexico last unwound their rambling disharmonia for their old township fans for upward of $60 a ticket. The musician you married (who’s the starfucker now?) only gets small gigs since COVID, and one of the last times he played solo at a toasty Tucson porchfest, the rubber-lizard-head-wearing crooner afterwards garnered more of a crowd, despite the muffled vocals and drum machine.

Even when you venture out of Tucson’s skin-crisping 112-degree days to visit mom back in Portland, it’s 97, and most apartment buildings there don’t have central air. The FAA scares you so much you don’t even want to fly there. And there’s an earthquake zone offshore that might someday soon send water gushing inland over the west half of town. So, you tell your 75-year-old mother, who can’t afford real estate and is again apartment-hunting, that maybe it’s a good thing she never bought in rich and hilly Lake Oswego: the cheaper eastside might be the only part intact and earthbound when the flood comes, so she should probably scout a spout there instead.

Since the 2024 election that Untied the States, Arizonans and Portlanders alike, along with everyone else who doesn’t suck presidential dick, aren’t “making it” right now: are held hostage by cost of living spikes, loss of services and free speech, or because they are brown and are hauled off to ICE camps where, reports say, inmates are made to eat and drink on their knees from dog bowls on the floor.

Because why would there be carpet?

You keep expecting the basic humanity you had become used to surrounding you, polite and gently curious, but more and more you feel this expectation is flawed: based on an outmoded soft-liberal model of reality, now usurped by people who, this whole time, just wanted to rule others under the approval of a god they invented in their own likeness, and who were fooled by a man into thinking he’s it.

It’s hard to come up with music or other creative endeavors that offer emotional strategies to address this terror: the daily feeling of sinking deeper and ever faster into the trap of “slave class” in a system designed with open jaws to circulate its freethinking inhabitants down a suction-spiral of debt, chronic stress, abuses, addiction, healthcare failures, jail, and a purposeful dearth of resource.

Meanwhile, the acquiescent rich get richer: foaming-at-the-mouth mouthpieces of mania, contented marionettes.

They clog up the courts to skirt regulations on growth, assisting an almost amoebic absorption, while the solitary or unsupported unhoused drown on Burnside or cook up on Alvernon.

Their data centers and shopping malls creep into the outskirts of the dehydrated West, diverting ever more water from thirsty mouths and small farms to industry giants with no concern for the particular set of factors and creatures that once made this space unique and special, and which will never be able to be reproduced.

Talk about the end of an era.

Strategies for emotional and intellectual survival you see in music and media now: an obsession with money, because the only way to stay afloat in this flotsam is to have it.

Sex appeal, but updated from a variety of shapes to a uniform of fake nails, boobs and butts.

A bunch of semi-privileged youngish hipsters throwing up their hands and saying “I’m on a self-care journey.”

They make blogs about where to camp while the wilderness behind their moody Instagram filters is sold off day by quickening day.

It's hard to know what to do when all the old responses you’d learned about don’t seem to work. Talk to people. Convince them of wrongheadedness. Persuasion and/or inspiration used to trump coercion in the land of 1990s creative culture from whence you came…Right??

Then suddenly you sit up straight in the middle of a random mid-August Wednesday night.

One of the most “fun” things about your 40s is the midnight wakeups: no reason. You exercised. Or you didn’t. You drank a glass of wine, or demurred. You took an allergy pill, or forgot it. Is the A/C failing? No…

And on this instance, right before you shock back into your darkened bedroom and find the glowing red clock screaming at you angrily, “Two o’clock(!!!),” you’d had a dream:

Your once-more-free and teenaged body is barreling down the stairs at Portland Gramma’s house and through the kitchen, on its way out the door to discover all the boon of the world beyond the protection and habit and biases of home.

“Wait a minute, Dolly.”

Her voice, warbly with age, matches the knobby hand she stretches out to slow you down. You’re not sure why she calls you Dolly, except that maybe Dolly Parton imparted a common lady nickname for her time: a time that Gramma wants back.

“I want to show you something.”

And you groan a little on the inside, cause you know it’ll be a long stop.

You pull up the tan kitchen chair she’s had since the 70s. There’s the mega tape-deck and speaker set from the 80s.

There’s the stack of old country tapes, stretching back to the 50s. Today she wants you to listen to Willy with her. Willy, who still rings true today and who your now-husband worships (did you marry your grandma??).

She wants to sing along to “On the Road Again” with you and tell you (again) the story of how she played piano during Prohibition.

How she and her sister were invited to go on the radio (not the local one), but they were farm girls, and they didn’t know what an elevator was.

The radio station building didn’t have a staircase.

So, they missed their slot to sing and make it big, simply by waiting too long in the lobby, unrecognizing this new technology used to move a mind and body up, or down.

You remember how sorry you felt for Gramma that she missed that moment to rise, with all that the idea implies. Wondered at the oddly-opening set of doors too long.

Of course, she eventually learned to use elevators, but you used to chide her, just a little after that anyway, as if suddenly, adapting was easy:

“Let’s get you a new toaster. Look, the cord is frayed.”

But she wouldn’t have it: returned the new beige abomination, pulled her trusty stainless steel unit back out of the trash and taped up the exposed wire, so attached to everything she’d known from before: stories, other objects, social norms and habits.

You always watched the toaster corner for smoke thereafter.

Yet you just did the same thing: the “look back,” like Lot’s wife, much as you hate to invite the overuse of Bible-as-guide.

You easily blame Bible-thumpers for trying to recreate an ancient reality they’ve fallen into imagining worked better than this one, just because they can’t envision anything else.

You’re so mad at “Muricans” who somehow imagine they would have been part of our once-Great Generation, over there fighting with the Nazis, while they vote for them now.

Nostalgia, you know, is sometimes described as a “homesickness” for the past.

Emphasis on sickness.

We’re just lovelorn for something that seems missing.

And yet here it is, the middle of the night, and you’re in the total dark cave of your room, realizing you’ve done the same: you’ve been scouring your emotional landscape for answers from the past, about how to exist in the present.

Have hope, keep the faith, rage against the machine, go to protests, sit on sidewalks, xeriscape, donate, recycle, get solar panels, get the vote out. Embrace subtlety, question power, use your power, assume people do their best. Be polite. Make a scene. Get arrested. Travel light. Commit to causes. Practice self-care, then radical acts of kindness.

Yes We Can turn our lemons into LemonAIDS!

Etc. etc. etc.

It’s all insufficient now, though it all surely mattered once.

Your deep and abiding nihilism, which frees you from a too-deep emotional investment in eternal human legacy, in humans needing to inhabit the universe forever or in the universe even existing forever, makes it perhaps better for you than for some others in terms of coping.

And the fact that this nihilism is also somehow nothing and everything at once in your mind. Extremes are everywhere but they melt together daily:

Sound is empty.

Crowds are empty.

Words are empty.

Chaos is on a slow path to fold into a hole.

When politicians say things, they mean the opposite, but both can be true. Or false.

Culture workers be damned if they can say anything.

Yet there’s a part of that nihilism that still, vaguely, expects there to be no new currently-shaped or confounding evils: no slaves, no rights curtailed, no torture or dogbowl drinking implements at all. Weren’t these ills meant to have been left in shadowy farback past? Aren’t we beyond it? There’s a too-sadness in giving it all over early.

A lingering sense of justice seems the only thing that calibrates and sensifies the increasing nonsensicalness, and it’s an enormous puzzle, to be sure: the path to spare this time and some still-sacred part of yourself and the other people in it from harm.

What to do?

In the absence of immediate answer, you think, nightbound, of Gramma, who always made you, despite your impatience, keep listening.

You think of the poet Caroline Forche’s dictator, his jar of ears on the ground, now scattered: the ears are dead and conquered, and yet still poised for the rumbling of in-marching rebels.

When will the moment arise that you will know your moment?

From where will the call or the insight arrive?

You understand you’ll miss it if you linger too long here, in yesteryear, or inhibit, too long and too deeply, your fear about a future everyone seems to think they can predict, but cannot.

Only then can you lay down and dream again, once you feel this clearing of your mind back outward to the senses.

The last time STRFKR came to town here in Tucson, you didn’t go. Same for Modest Mouse. You were even offered a free ticket!

But they played too late at night for your new old-person bedtime.

Or you felt, too keenly, the loss of a time when you thought you still felt free.

Maybe you should’ve gone anyway. Not for the purpose of trying to re-live a thing, but because the message you need might come in the unexpected bend of a power chord or a synth note you thought you forgot, if you were to listen deeply.

It’s worth noting it could also appear in the curve of a brightly Botoxed lip, if you keep your eyes wide.

It could be subtle as wind in a cactus.

You don’t know yet.

But step one is still, always, imagining an elevator.

Lydia Paar writes essays and stories. Her works have been noted in Best American Essays, won North American Review’s Terry Tempest Williams Creative Nonfiction Prize, been nominated as a finalist for New England Review's Emerging Writers Award, Pushcart and Best of the Net prizes, and published in such magazines as Huffpost, Literary Hub, The Missouri Review, Essay Daily, Witness, Farmerish, Hayden's Ferry Review, and COMP. She serves as co-editor for The Nomad Review and teaches writing at the University of Arizona. Her first full-length essay collection, The Entrance is the Exit: Essays on Escape, was released in 2024 from the University of Georgia Press.