the sweet 16

(16) king’s x, “dogman”

outlasted

(13) fugazi, “waiting room”

591-356

and will play on in the elite 8

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on March 20.

TO BE A GOOD MAN: PATRICK MADDEN ON "DOGMAN"

Dogman (song)

From Patrick Madden, the free essayist

|

|

This

essay is hopelessly biased beyond the possibility of impartiality.

Indeed, its author does not even attempt to hide his blatant

subjectivities, as if he doesn't believe in an objective

worldview. Please help resolve this issue by giving "Dogman"

your March Plaidness

vote.

|

| "Dogman" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Single by King's X | ||||

| from the album Dogman | ||||

| Released | 1994 | |||

| Recorded | Southern Tracks (Atlanta, GA) |

|||

| Genre | Grunge / Hard rock | |||

| Length | 4:01 | |||

| Label | Atlantic | |||

| Songwriters | Jerry Gaskill, Doug Pinnick, Ty Tabor | |||

| Producer | Brendan O'Brien | |||

| Influenced | AiC, STP, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, etc. | |||

| King's X singles chronology | ||||

|

||||

"Dogman" is a kickass grungy song by the underrated and underacknowledged American band King's X. It was released as a single in support of their 1994 album Dogman.

Grunge

As a noun, nothing pleasant: filth and grime, repugnance and odiousness; a "word used in TV commercials about scum on your shower curtains" (according to Soundgarden bassist Ben Shepherd); backformed from grungy, itself perhaps combined grubby and dingy. If not quite onomatopoetic via sound, then perhaps by feel?

But as a musical style and attendant culture, a kind of anti-revelation: discordant, distorted guitars; lackluster vocals; melancholic lyrics; "artless" live-like production. Grunge is unflashy, dispassionate, ironic, apathetic, everything '80s pop (and hair metal) was not. And despite the variety of styles coming out of Seattle in the late '80s, even on SubPop Records, once the marketers got hold of the label, grunge became what sold.

Essentials

For Doug Pinnick, King's X's bassist and most-time lead vocalist, it all comes down to one simple thing: the guitar's (and bass's) low E string tuned down to D. "Grunge, to me, is drop-D songs. It's not Seattle. The whole world drop-D tuned within a year…" And this, more than any regionalisms or individual musicians or producers or executives, led to the explosion of so-called grunge (and adjacents) in the 1990s.

Personal Life

Lehi, Utah, and Los Angeles, California, 2021

I decided to have a chat with Doug. It had been over a decade since I'd seen him, nearly three since we'd had any kind of regular contact. I was nervous, but I needn't have been. He readily agreed and, when he Zoomed in, greeted me warmly, recalling past conversations and correspondences as if we were old friends, which I'd dared not claim, but which he readily acknowledged. "Those letters I wrote…" he said, "they never were letters of 'I'm Doug Pinnick, a rock star and this is a fan.' It was always, 'this is my friend'… it's a friendship thing. … Friendship is way better than being a rock star."

Grunge

Origins

| Song | Band | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Dear Prudence | The Beatles | 1968 |

| Moby Dick | Led Zeppelin | 1969 |

| Cinnamon Girl | Neil Young | 1970 |

| Ohio | Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young | 1970 |

| Black Water | The Doobie Brothers | 1974 |

| Fat Bottomed Girls | Queen | 1978 |

| Drop Dead Legs | Van Halen | 1984 |

"The quickest way to get a whole generation to change the way they're playing is to do something that any kid can pick up his guitar and play immediately," says Doug, crediting Limp Bizkit's Wes Borland with the idea, and I believe them. I suspect nobody can really tell me who "invented" drop-D (such a slight variation from standard EADGBE tuning, in which the low E string is flattened a whole step to a D, thus allowing "flat fingered" barring on the lowest three strings, producing a ready power chord), but a bit of superficial research reveals that this simplest of variations has long been used in blues and bluegrass, and it appears on plenty of rock songs long before the '90s.

King's X and Soundgarden, 1988

Despite my just mooting the question, Doug makes a pretty good case that King's X's debut, Out of the Silent Planet, ushered the style into much more widespread use than before. "We came out with Drop D tuning in '88, and Soundgarden came out in '88 with Ultramega OK. Our record comes out, same time [King's X released their album 7 months before Soundgarden, in fact], never heard of each other. I think when both of our bands [recorded in drop D]—we did a whole record like that; they only had one song ["Flower"] like that…" Doug trails off, but his point is clear, that these albums began something that would soon catch on.

"When I talked to Kim Thayil about a year ago," Doug continues, "he told me that he introduced Chris [Cornell] to drop D tuning in '85. But they didn't really write anything. And Ty [Tabor, King's X guitarist and second-most-prominent-lead vocalist] wrote 'In the New Age' in 1985. And he said, 'This is bluegrass tuning. I just wanted to do something that I felt like was what I'm going for, like Beatles metal.' Whatever that muse was, he was talking to Ty and he was talking to Kim. I believe the muse had to talk to those two guys to tell us, because me and Chris took off and ran with it. When we both heard the drop D tuning, seems like almost everything we wrote had something to do with that; it started happening at that point. A lot of our songs became similar. 'Black Hole Sun' sounded like a King's X song. 'Outshined': people called me up and said, 'Dude, Soundgarden's ripping off King's X again.' There were a lot of similarities. Not to say he was copying us. What I'm trying to say is we were pushing each other without knowing. When I was introduced to drop D tuning, it just opened the whole world up."

It seems futile, honestly, to seek the kind of "credit" so many people are interested in locating with this or any other question of originality, a fact that Doug readily acknowledges ("A lot of us who were 'innovators or inspirational,' we're the ones who didn't get the glory or the money; it really humbled me and helped me realize that we still are a part of this.") But we should all acknowledge, as have so many musicians in so many of the wildly popular "grunge" bands, that King's X, musicians' musicians all, were right there in the early mix, beloved by and influencing others.

Personal Life

Notre Dame, Indiana, 1990

Imagine with me this scene: a young man in red plaid jacket and scraggly hair trudges across the frozen fields south of campus toward the record store. His friend, now graduated, has written him recommending a band he describes as "hard rock with a conscience." The young man sometimes feels alone, especially now that his friend, with whom he would play cards and listen to music and make silly faces, has gone. He would not admit this. Often he sits on his floor and plays his records, studying the liner notes, singing along, abiding in melancholy. When he finds the CD in the stacks at Tracks, he's intrigued by the ornately "carved" biblical stories in the block letters of

FAITH

HOPE

LOVE

and the blatantly metaphorical daisy poking out of a vast, dry, cracked landscape on the back cover. He lays down his $12, then trudges back to campus. As he sits on his dorm room floor and unwraps the King's X CD, places it in the player, presses PLAY, he understands viscerally that he has found exactly what he has been looking for, without quite knowing it.

Grunge

Seattle, 1988

Without claiming too much, offering that this is what was reported to him, and you can believe what you want to believe, Doug recalls the band's visit to Seattle in support of their first album. The venue was "really small," he says. "I looked out the back door and you could see the bay. We played for like 30 people. And you know what we sounded like, … so I know that we impressed them, but I didn't think that they liked us. Well, about a year later, I remember coming home from the road and I turned on Headbangers Ball, and every band was drop D tuned except Bon Jovi. And I went 'what in the world has happened?'"

What had happened may have been what Richard Stuverud, the drummer, later reported: "'Hey, Doug, you know, every band in town was at that show.' Nobody went to see bands in Seattle but people in bands, because nobody cared. All the bands would go if it was a national act. So, basically, we played for a house full of musicians. A lot of those guys in a lot of those bands."

Maybe you already know this, about drop D, or maybe you only notice a general low-key vibe in the popular music around the turn of that decade, but for confirmation, here's Rick Beato, a former producer and current YouTube musicologist, recalling that "I was in drop D…for years. My guitars were only tuned in that tuning, because every heavy band from the early '90s through 2012… almost all their songs were in drop D."

Personal Life

Whippany, New Jersey, 1991

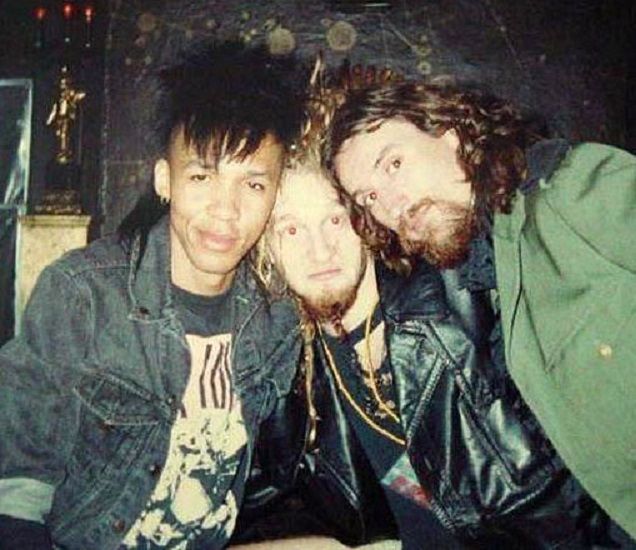

(L to R: Pinnick, Gaskill, Tabor)

This was before cell phones, at least for me. I was working as a janitor at the sprawling AT&T campus down Whippany Road, which work afforded me plenty of time for reading and listening to the radio. All month I'd been calling into WDHA for entries into a drawing to attend a special King's X acoustic breakfast show at the Catalina Bar & Grill in Cedar Knolls, giving the phone number for my boss's office. As I packed my things to go home for the day, disappointed that my name had not been announced, the phone rang. Because some of the winners couldn't make it, I was in. My friend Joe and I (two halves of our unsigned band The Tords) arrived at 8 AM the following Monday to find Doug Pinnick, Ty Tabor, and Jerry Gaskill eating breakfast around the bar, a bit shy but generous with their time to chat, sign autographs, take pictures. We found them to be humble and friendly, utterly egoless, unhierarchical. As they sat down on a six-inch riser to play, amplified but just barely, effected only minimally, Joe and I sat cross-legged on the floor in the front row, awash in the lush grooves and angelic vocal harmonies, smiling from beginning to end at the tightness and innovation of the sonically naked three-piece in front of us.

Genuineness

When I was young(er) and foolish(er), more susceptible to fawning obsequiousness, I wrote earnest letters to Doug and he wrote back, generously and genuinely, sometimes including bootleg cassettes of live performances (Woodstock '94, etc.) or demo tapes, once sending a selfie (pre-digital, holding a red point-and-shoot over his eye in a mirror) after he'd braided his signature Mohawk. After every show, he and Ty and Jerry would appear in the parking lot or alleyway next to the venue to visit with fans, sign autographs, take pictures, as many famous folks do, I suppose, but over the years it became clear that Doug was remembering people, asking followup questions, having real conversations, keeping up with our lives. Once, I met three members of Dream Theater after a show, when they gave their new CD (Images and Words) to Ty. Once at a show in Manhattan, I caught Will Calhoun of Living Colour as he stage dove during "Moanjam." At that same show, same song, for reasons unknown and unknowable, my neighbors cleared out when Mark Poindexter of Atomic Opera dove off the stage, leaving me alone to absorb his momentum. To the floor we both went, and with a "sorry!" and a hand to help me back to my feet, he was gone. After the show, in the alleyway next to The Ritz, I overheard him telling a friend, "I tackled a poor guy!" and I sidled up to say, "That guy was me!" Once I arranged with Doug to attend the soundcheck for their Long Island show, and I brought along my younger brother and his two friends. When we discovered that it was an over-21 show only, Doug talked with the venue's management and got us all in anyway. Once, after I'd been gone on a Mormon mission for two years, missing the Dogman album and tour entirely, I went to a King's X show in Philadelphia with that old friend whose letter introduced me to the band years before. During a vocal break in the opening number, "The Train," Doug scanned the crowd and, eyeing us a few rows back, said, "Hey, Pat!" with an enthusiasm so genuine that even my friend, whose name is also Pat, felt it, and I remember it warmly to this day.

Dogman (song)

The result of a Lennon/McCartney-like musical rivalry, and a devastating break with their long-time manager, whose financial finagling left the band with nothing but their name, "Dogman" (the song's title was also used for the album) comes from a time of anger and uncertainty. Ty Tabor, who wrote the song, says that "it's kind of disjointed artistically, on purpose, and trying to express that feeling of not standing on solid ground… The thing is, I write lyrics because I don't know how to explain what I'm feeling. "

Ty's original demo used "to be a good man" for the chorus, which he and everybody else in the band knew wouldn't fly, but I still believe in that underlying sentiment whenever I hear it. The replacement phrase "to be the dogman" is typical King's X ridiculousness (see Gretchen Goes to Nebraska or "Charlie Sheen" or Ogre Tones). According to a Doug Pinnick interview at Songfacts, "Whenever King's X has an artistic decision to make, if we can't come up with anything, whoever comes up with the stupidest thing, we'll go for." Doug remembers that after everyone tossing about plenty of colorful adjectives, he threw out "let's just call it 'to be a dog man,'" and the phrase brought new peals of laughter and band agreement.

That's one of the things I love about the song: its juxtaposition of the solemn and the inane, the jumble of images from light bulbs to powder to books to horse races to business luncheons to "leaves in need of raking," suggesting poverty and prayer and pain and depression, instabilities and vertigos that the driving guitar, bass, and drums confirm and complicate.

(unknown date, venue)

Musically, the song came from Tabor and Pinnick's friendly competitiveness, "like two guys in a race," Doug describes it, "trying to write the best, baddest, biggest tune." And he's proud of the results: "I feel like we came to a place where we kind of understood what was going on with the King's X sound. We were very angry by how we were manipulated by [our previous manager]. We wanted to be that band that slammed you in the face like we were live. Ty said he wanted to write the baddest-ass riff he ever wrote in his life, and it is, probably one of the best riffs ever, in my opinion, and I'm jealous of him, because I wish I had written it." Drummer Jerry Gaskill remembers that the band wanted the record "to be so heavy that it sounds like big monster creatures are walking through the town, and they're crushing everything." Nuno Bettencourt, of Extreme, writes that "when I hit play on ...Dogman, I nearly drove off the road I was so pumped." Mick Mars, of Mötley Crüe, says that "my favorite [album] is Dogman." Jeff Ament, of Pearl Jam, recalls of this period that "[King's X] were one of my two or three favorite contemporary bands at the time." While I've got you here, let me add that Andy Summers, of The Police, said " I think they’re easily one of the best rock trios anywhere. I don’t think they’ve been equaled." And Billy Corgan, of The Smashing Pumpkins, believes that "They were really ahead of their time. If you listen to the music that followed, they really figured things out that took many bands ten more years to figure out." (You can find these quotes and more in King's X: The Oral History by Greg Prato.)

Personal Life

Lehi, Utah, 2021

of King's X memorabilia

I've discovered (once again) that it can be uncomfortable to revisit one's past self. In my case, to find some of my awkwardly fawning letters, to see evidence of my obsession played out in a stack of photocopied articles and interviews, dozens and dozens of bootleg tapes and CDs, many of which I made myself with colorful inserts and liner notes, and to realize that although I still have this cache of King's X memorabilia, it's been sitting in a box at the back of the closet under the stairs for nearly two decades. So much of what was once essential to me is now just an asterisk. Which is not to say that I'm embarrassed by the music or my enthusiasm for it (I'm still a fan; I still listen intently and feel inspired, and not just for nostalgic reasons), but by my approach to it. Or maybe I'm simply realizing that what was once so important is now only ancillary, and that I cannot quite access the ways these influences have played out in my life (and yet here we are, bringing my musical obsessions into my writing). All this is well and good. Then I was single and shielded from serious responsibility. Now I am a husband and father (to six children) with a rewarding and time-consuming job, so thank goodness I no longer have time to create and distribute a monthly King's X fan newsletter. And it brings a strange kind of hopefulness to return to all these relics and to try to reconnect with such an earnestly invested past self. That guy was sure a nerdy ingénu, but he was unabashedly enthusiastic and sincere. Sometimes I miss him.

Influence

(unknown date, venue)

There's an inevitable argument inherent in this essay, despite my wishes to avoid it (because it's been made so many times before, to no avail; because it's too late; because questions of credit and originality are inescapably convoluted; etc.): that among the infinite converging factors that gave rise to the woolly thing we recognize as "grunge," King's X was central, particularly with their first few albums, though they were never quite invited onto the bandwagon that parted from Seattle in 1991 to conquer the world. So it's fruitless to make bold claims, or to ignore the circling swill of influence that was this particular time in American music. Influence never flows only one way anyway. Doug readily admits to rushing right out to buy the first Alice in Chains EP; to chatting/plotting (about crooning!) with Chris Cornell during the recording of Dogman and Superunknown; to wishing King's X were invited along the Lollapalooza tour (but Perry Farrell, as reported by one of his bandmates, thought King's X was "pretentious bullshit"); to believing that King's X were "too spiritual and Christian and pretty" for the scene, like "the Bee Gees" with their gorgeous vocal harmonies; to putting on a prerelease copy of Alice in Chains's Dirt and discovering "everything that I wanted King's X to do, be, and sound like. I was so disheartened that I couldn't play side two" (meanwhile recalling a story about Layne Staley running down the street after Jerry Gaskill to joke "Keep writing great songs so we can keep stealing your shit").

"They were like my kids," Doug muses (having just turned 70 last September, while most grungers are somewhere in their 50s now). "They looked up to me; they had this innocence about them. From the day I met them all, they were respectful." Maybe that's the word: respect. Not credit or influence, not a fruitless argument about who came first with what new thing. But mutual respect among people caught up in this unexpectedly popular musical movement.

Pre-rock

It's worth mentioning, if only briefly, that nothing is created ex nihilo, and musical genres and subgenres come not from individual geniuses in isolation, but from recombinations of past works passed through and reformed by multiple consciousnesses. In the case of King's X, some of these include utterly un-grungey Sly and the Family Stone, Curtis Mayfield, Yes, Led Zeppelin, Chuck Berry, KISS (this list is shamefully shorter than the one Doug would provide), and even the Andrews Sisters, whose "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy" inspired similarly tight vocal harmonies on "We Were Born to Be Loved." Having grown up in the 50s, at the birth of rock and roll, Doug appreciates so many musical styles that it is nigh impossible to unravel and trace the various threads of influence on the sounds he, with others, now creates.

Form

I have tried to remind us of the incredible, ineffable complexity of interrelations by writing this essay in the form of a Wikipedia article, to suggest, via links and collaboration and eternal internal incompleteness, that everything is connected, that nothing is original (nothing is origin, nothing self-evident, nothing primely moving). We recognize the fonts and arrangements, despite this new venue here at March Plaidness, and we are keen to discern how the author has played within and worked against our expectations for the thing we know, how he has conformed to and subverted the form, and how those choices contribute to meaning.

"Everything I've ever done in my life," says Doug, speaking of his myriad varied influences, "I put my own twist to it, I try to be outside the box. Everything I write, I try to take it outside the realm somewhere. I still want to find something in there … that makes you move, that makes you go 'I never thought of that before.'"

I really do believe that King's X is a major node within the site map of grunge, and the song "Dogman" an example of the band circling back to become what it had influenced others to be. And while claims such as this may evoke agreement or disagreement, provoke deeper thinking or dismissal, I want again to send us outward, to glimpse the big picture, maybe even blur our vision a bit, and float free from argument, feel grateful just to be here.

Audience

— Charles Lamb "New Year's Eve"

I'm writing this essay amidst and against various assumptions about my audience, starting with the split/combination of song and essay. Is this March Plaidness competition about the music or the writing? Do site visitors click through to watch the videos? Do they read the essays? Are they fans of King's X here to support their favorite band? Are they friends of mine cajoled here by my request? Are they long-term participants in the March Xness tournaments who enjoy reading and learning about new songs or revisiting old songs they haven't heard in a while? Are they seven-year-olds responding without guile? Will they recognize in my essay the same old story they've read so many times before, about how King's X doesn't get their due, how they were supposed to make it big but never did? (Vernon Reid, from Living Colour: "I feel it's only a matter of time before that band is the biggest band in the world.") About how the world is not just?

Repeating Himself

It occurred to me as Doug and I spoke that the poor man is relegated to repeating the same stories and same explanations he's shared hundreds of times. In the old days, when information was more localized in newspapers, on radio shows, this was an appropriate way to spark interest or satisfy curiosity in different places (ahead of a concert, for instance). But with the rise of the internet and the dispersion of ubiety, to the nth power amidst a pandemic, everybody with enough interest in a subject seeks out (or is presented with, by the algorithms trained to train us) the same information no matter who does the interview, no matter where they're sitting during the conversation. Doug is good-natured about all this repetition, perhaps with a peripheral thought about promoting the band, but more prominently with that same genuine interest in talking with a friend, sharing stories, marveling at how things have gone, grateful for the journey's unexpected and even disappointing meanders. "People think that we're hurt, or feel bad about everything that happened," he says. "I wouldn't change a thing. Not a thing. Because I wouldn't be the person I am today, and I'm finally OK with me. The other thing is, there's a lot of people in my life that I wouldn't know and would never have met and loved, and gotten so much love from. To know that that wouldn't have happened… I'm all good."

In conclusion

I'm tempted to invoke Jack Handey's "Deep Thought" about

If you're traveling in a time machine, and you're eating corn on the cob, I don't think it's going to affect things one way or the other. But here's the point I'm trying to make: Corn on the cob is good, isn't it?

which always comes to mind when I've been taking our thoughts away, thinking about other days, writing about who knows what and the kitchen sink, and suddenly I want to wrap things up? Who do I think I am? But really all I want to say is how much I love, genuinely love, this band and this man, whose music and personal generosity have meant so much to me, not in an ironic, disaffected way, but as somehow central to the person I wanted to be and, in some small measure, became. Which may be precisely the attitude, and the reason, that prevented King's X from ever making it big. But they're still around, still making music, still taking the time to be part of our lives. So there's that.

External Links

- King's X official website

- "Dogman" live on the Jon Stewart Show

- "Dogman" live at Woodstock 94

- David Cook, American Idol runner-up, covers "Dogman" (w/ Jerry Gaskill)

- Ari Koinuma explains "Why ['Dogman'] Hits So Deep"

- All clips from Patrick Madden's 1/14/21 interview with Doug Pinnick

- March Plaidness contenders

- Criminally overlooked awesome songs

- Unrecognized geniuses

- Influence sponges who generate utterly vibrant and new sounds

- Sine qua non of grunge

- Humble, friendly people who don't let fame get to their heads

- Everybody's influence

- Everybody's friend

- Musicians' musicians

- Finding contentment in the little and the local

- ESSAYS!

Patrick Madden, author of Disparates, Sublime Physick, and Quotidiana, agrees with Pearl Jam's Jeff Ament that "King's X invented grunge."

brad efford on “waiting room”

“If you ask me what is Fugazi about, I’d say Fugazi is about being a band.” —Ian MacKaye

I am sitting on the couch in my living room. My apartment is small but bigger than the last one. There is room enough for me to spend the day’s working hours working at the kitchen table while my wife spends them working in a small office downstairs. It is the only room downstairs. The previous tenants made it an uninsulated second bedroom. There is room enough in this apartment for our two cats to migrate sleeping positions throughout the day: living room couch, downstairs office, bed. I’d like to change the subject. If I think too much about the confines of the rooms my life now takes the shape of, something in me starts to seize.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room. I am watching a movie. I am scrolling social media. I am listening to the same collection of songs again. I am writing this essay. I am pretending to write this essay. I am not sure what the couch in my living room feels like. It is not particularly comfortable. It is gray, it is stained, the cats have ripped its arms so that the stuffing shows. I don’t see any of this anymore. It is where I sit. I prop my legs up on a small wooden bench we’ve turned into a coffee table. It is not particularly comfortable.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room, thinking. I am thinking about the game I used to play as a kid, the game where two opponents turn a page full of dots into squares, drawing segment after segment until the page of dots becomes a page of boxes. This is the way I’ve become accustomed to seeing my life. I have a hard time telling whether the point is to keep making boxes or stop my opponent from making their own. I have a hard time telling who the opponent is, though I think they look and think like me.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room again. I am listening to Fugazi; Fugazi is happening to me. I am thinking about how the Fugazi song “Waiting Room” is like the song “When Will My Life Begin” from the Disney movie Tangled. I am thinking about the ways I’ve wasted my life noticing parallels like this and trying hard to forget them again. I don’t believe in “wasting” time, though, not really. Time will waste itself, and we will spend the waste however we are moved to spend it. I do not feel guilty about spending time that is wasting itself. I try to create, I try to do good, I try to give to others who need it, but I do not feel guilty about time. Waste is a concept we built when we built the systems that drive us. The music is good and my thoughts are fleeting and mean nothing and you might call this “vibes.”

I am sitting on the couch in my living room watching the Disney movie Tangled. It’s about Rapunzel, whose best friend is a chameleon, which must be a part of the fable that I missed as a kid. Rapunzel sounds like Mandy Moore, who sang “Candy,” a song that came out at the end of the summer I was eleven years old. “Candy” is about someone waiting for someone else to notice them, come to them, and give them release. “This vibe has got a hold on me,” Mandy Moore sings. “Show me who you are.” The desperation is invigorating. The waiting’s the entire game. In Tangled, Rapunzel lives with some degree of Stockholm syndrome at the top of a very tall tower, trapped there by a woman pretending to be her mother—an admittedly unusual situation. In “When Will My Life Begin,” here are all of the activities Rapunzel participates in while waiting for her life to begin:

sweeping the floor

waxing the floor

doing the laundry

mopping the floor

reading 1-3 books

painting multiple paintings

painting the wall

playing guitar

knitting

cooking

doing a puzzle

playing darts

baking

making papier-mâché

ballet

chess

making pottery

ventriloquy

candle-making

stretching

sketching

climbing

sewing a dress

brushing her hair

Punzy isn’t getting paid to do any of these activities, obviously, and even if this were real life and not an animated Disney movie, chances are still slim that she would be getting paid to do them. They are simply ways to pass the time. She is waiting for her life to begin. All of this nonsense—the games, the art, the tailoring, the reading—is only white noise. Nothing but hold music on the phone call that is her life. This song depresses me.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room and reading back through all the time I just spent on a song from the Disney movie Tangled. I am preferring to understand it as something time spent doing to itself while I went along for the ride. I am choosing to see this writing as meditation, as holy, as worthwhile. “I am a patient boy,” Ian MacKaye says in “Waiting Room.” “My time’s like water down a drain.” I don’t think he is frightened, or complaining. He sounds content, almost defiant. He sounds like someone who is waiting not for something to happen, but for the event of waiting itself. He is planning a big surprise. He’s gonna fight for what he wants to be.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room. I am wondering what I want to be. I am considering what to fight for. In Instrument, Jem Cohen’s Fugazi documentary, Cohen asks a fan waiting in line for a Fugazi show what the band means to them. “What do they mean to me? Well they don’t mean anything to me. They’re just music.” The fan laughs derisively. This moment is a triumph. It feels like a perfectly succinct distillation of everything the band has been trying to achieve in its tenure. “Fugazi is about being a band,” Ian MacKaye says earlier in the movie, making a point about purpose in as few words as possible. Choosing to use time as a medium to make art, form community, be together. This sounds like a dream come true.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room, listening to “Candy” by Mandy Moore. I like the song, and I am enjoying myself tremendously as it plays on repeat. Show me who you are. I am trying not to analyze the lyrics, as there isn’t much to analyze. I am happy that Mandy Moore made the song, and happy it afforded her a lifetime of unlimited monetary options and me a lifetime of one great option: listening to “Candy” whenever I want to. I think what she has done with time is as rewarding as what I have done, and I have done practically nothing. I wait, I wait, I wait, I wait. I am showing you who I am.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room. I am sitting on the couch in my living room. I am sitting on the couch in my living room. I am sitting on the couch in my living room. I am sitting on the couch in my living room. I am wondering when will my life begin. I am manifesting control over time; I am letting time roll through me. I am fighting for what I want to be; I am being.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room. Guy Picciotto, guitarist and singer for Fugazi, is explaining why global celebrity is flawed. The band would rather create a community that is choosing them at every turn, following the invitation the band has sent rather than finding them unavoidable, in their faces, on their screens, unasked-for, undesired. This is why there is no fighting at Fugazi shows, no meanies allowed: community is key. It’s the entire enchilada. It is what everyone in the room is fighting for. It’s who they want to be. I think this is so beautiful it almost seems unattainable, more vision than reality, though I know it existed, I know that it happened. I know it like I know an ancient legend, like I know all the words to a song no one cares about, and right now just the knowing is fulfilling, just the ethos is enough.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room, uncomfortably considering all the things I have not done. I am giving myself official Pandemic Permission not to grieve this as a loss, but translate it forward into the future, to take the feeling of serenity with me as I go. I am sitting on the couch in my living room, and this is my life, it is beginning every moment. The beginning is the moment, the waiting a warm, inviting void. I wait, I wait, I wait, I wait, until my waiting turns to mantra. I cook, I sweep, I puzzle, I paint, I read, my every moment a new way to show me who I am. I am a patient boy. I am sugar to my heart.

I am sitting on the couch in my living room playing the dot game, making boxes with myself. Against myself. I’ve decided it doesn’t make a difference. We are connecting the dots to make boxes. We are counting each box as a win. Time and me, in tandem. We are playing the same game, on the same couch, in the same living room, together. We are doing it together. Another line, another box, another win. Waiting, but waiting for each other, waiting for our turn. No. The lie is that there are turns. There are no turns. We are simply waiting, here, together.

Brad Efford is the founding editor of The RS 500 and wig-wag, a journal of personal essays on film. He lives in Berkeley, California.