second round

(1) Dexys Midnight Runners, “Come On Eileen”

turned down

(9) M|A|R|R|S, “Pump Up the Volume”

271-209

and will play in the sweet 16

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls close @ 9am Arizona time on 3/14/23.

EM PASEK ON “COME ON EILEEN”

“Come On Eileen” is a masterclass in unabashed corniness. There is simply nothing that can possibly be taken seriously about a grown man adopting a falsetto and the perspective of a teenager who is soulfully attempting to seduce his girlfriend by talking about how depressing their hometown is, all while his friends chime in with little nonsensical asides like "too-ra-loo-ra too-ra-loo-rye-ay" and some peppy strings play a jaunty little countermelody in the background. Any attempt to defend the song’s merit by defending its musical credibility only makes it sound more ridiculous. (Oh, it merges the sounds of Celtic strings and a Motown-esque beat? Still silly. It samples an Irish folk song about still liking your partner when you both get old and they aren’t hot anymore and concludes with an a cappella verse from the same? Even sillier.) And the song's pop culture legacy doesn't do it any favors in the non-goofy legitimacy department, either. (Most of the folks to whom I've chatted about this song associate it with Dean of Greendale Community College making up silly little lyrics to its tune in Community.) Ultimately, though, “Come On Eileen” doesn’t need to be serious: its beauty lies in how uninhibited it is. It’s a song meant to be howled in karaoke bars and played over and over again on long drives, _________.

Behind its lovely absurdity, though, there’s a hint of darkness in “Come On Eileen” that suggests that something not-so-fun was going down when the song was written. It’s there when frontman Kevin Rowland takes a second away from crooning about being horny to allude to the “beaten down, eyes sunk in smoke-dried face” of the people around him. It’s in the odd attribution of the single to “Dexys Midnight Runners and the Emerald Express”, suggesting some kind of division among the people who recorded it.

The idea that something charming and unserious can result from a period of struggle is nothing new. After all, we live in a world where goofiness levels reaching a fever pitch in the misery pit of the past few years necessitated the popularization of the phrase "goblin mode" just to accurately describe what everyone's whole deal was last year.

THESE PEOPLE ‘ROUND HERE

The deep-seated conflict at the core of Dexys' story goes way beyond anything that a reasonable onlooker might expect from an ensemble with only five albums to its name. They've spent their forty-some years of on-again, off-again banddom breaking up; making up; and near-constantly onboarding, losing, and occasionally regaining members: as of this writing fifty-one individuals have, at some point, been counted as members of the band. Those hardy souls who persisted through multiple album cycles were treated to whiplash-inducing stylistic and lifestyle changes, record label disputes, and endless infighting for their trouble. At the heart of this constant churn is the band's founder and only consistent member, Kevin Rowland, a man who is extremely serious about being serious about music and who, for much of the band’s history, held that virtue above all else.

On the spectrum of all-consuming experiences that it is possible for a person to endure, being a member of Dexys in its heyday sounds like it might have fallen somewhere between "being a member of an extremely weird military unit" and "joining a fairly ill-managed cult that never got completely out of hand because you could walk out before things got completely out of hand". You had to wear a uniform, which changed dramatically to suit Rowland's idea of what a serious band should look like every couple of years. You were expected to participate in a mandatory athletic training regimen alongside your bandmates. If you, like most of the band’s members, were English, you might be assigned a more Irish-sounding name to suit the group’s Celtic image. (Rowland himself was born in Ireland and has resided in England for most of his life.) If you were recruited to the band as a horn player, you might, seemingly on a whim, be instructed by Rowland to take up strings. And your time in the band would most likely be marked by periods of intense secrecy – from your label, from the press, and maybe even from your fans.

Too-Rye-Aye, the dreadfully-named album on which “Come On Eileen” appears, was recorded in a period of particular turmoil for Dexys. It doesn’t sound like anyone was particularly happy with what went down: half the band had one foot out the door after reluctantly agreeing to stick around for the recording, Rowland apparently hated the way the album was produced, and by all accounts the process of trying to promote the single was exhausting.

As of this writing I am two and a half years into a PhD program and still relatively fresh off of a stint in corporate America, which means that like most members of Dexys in the 1980s, I know a thing or two about trying to make something worthwhile in an environment where nobody around you knows what they’re doing and you’re constantly subject to vague instructions and mercurial demands from higher-ups who seem to have no concept of what they’re asking of you.

I don’t find Rowland entirely unsympathetic—after all, whom among us has been spared the agony of being stuck working on a project with a bunch of people we feel aren’t taking things seriously enough – but it’s easy to see why Dexys was, under his leadership, ill-suited for long-term success.

THINGS ‘ROUND HERE HAVE CHANGED

Making sense of the particular magic of “Come On Eileen” is made more complicated by the fact that Rowland has refuted, contradicted, and reevaluated almost every single aspect of the origin story behind his band's best-known song so many times that it's almost impossible to sum it up without sounding like a wide-eyed madman standing in front of a corkboard covered in red string. The first incarnation of his story was pretty normal: Rowland's first love was a girl whom he had called a friend for his whole childhood. When he was thirteen, their relationship became romantic. Rowland was an altar boy, and although the conflict between his Catholic upbringing and his newfound feelings was scary, but it was also intoxicating. Though the relationship didn't last, the memory of those emotions stayed with him. This is a nice story: sweet and simple and just relatable enough to keep it from being too embarrassing, just like the song that it inspired. It isn't true, though. Rowland didn't write the song with a childhood girlfriend in mind. Instead, the song's iconic chorus once bore the confusing and self-congratulatory lyrics "James, Stan, and me," referring to James Brown, Van Morrison, and Rowland himself and their shared musical legacy in the genre of soul. (The substitution of "Stan" for "Van" is apparently part of some convoluted inside joke that Rowland had at some point in his youth and that he legitimately believed would make sense to a broader audience.) Rowland has, at various points, stated that he changed the lyrics to make a point about Catholic repression, or just because he got angry in a session with his label.

Years after the dissolution of Dexys Midnight Runners and deep in the doldrums of a poorly-received solo career, Rowland made a confession that might have shocked the world had the world not largely moved on from him and his musical endeavors: he had stolen “Come On Eileen”.

Here's what happened, according to Rowland: at some point in the leadup to the recording of the second Dexys album, Rowland's ex-bandmate, Kevin Archer, who was a founding member of Dexys but who had already left the band, recorded a demo tape which featured a particular mix of Celtic strings and a "bum-da-dum" bass line that sounded like something off of a Motown record or maybe a Tom Jones single. Rowland listened to that demo tape, and he knew from the moment that he heard it that he needed it to be his. He recorded Archer’s song as his own, making up a story about falling in love as a teenager to sell it as an original project. The song was a sensation, but it was also the band's downfall. Rowland's friendship with Archer deteriorated over the theft, his band fell apart, and neither he nor any of the musicians with whom he had once been associated managed to achieve the “Come On Eileen” career high ever again. Years later, apparently still wracked with guilt, Rowland confessed to stealing the song publicly.

In more recent years, Rowland has recanted this confession. Today, he says that, suffering from depression and impostor syndrome after his most recent failure as a solo artist, he overattributed the song to Archer when, in reality, he had merely taken inspiration from the combination of beats and string sounds that his now-former friend had used.

What is “Come On Eileen” actually about?

The thing that really stands out about Come On Eileen is that Kevin Rowland really loves music and really loves talking about where he got his ideas. The song wears its influences, from – and yes, even his ridiculous “James, Stan, and me” lyric and the – all speak to

NOW YOU’RE FULL GROWN

“Come On Eileen” isn’t a good song. It’s a perfect song, the kind that you can come back to forever.

Dexys is still kicking, somehow. Some of the band’s former members have come back, and the group’s lineup has been somewhat consistent for the first time since it formed. They’ve got a new album coming out this year, and while their modern-day output isn’t likely to achieve what ““Come On Eileen”” did, it’s been well-received by critics and fans and everyone involved with creating it seems a hell of a lot happier than they did in the 1940s. And Rowland mentioned in an interview a while back that he and Archer spoke during lockdown and came to the conclusion, once and for all, that Rowland is not a song-stealer, so that’s nice to have settled.

In 2022, Dexys released Too-Rye-Aye (As It Should Have Sounded), a 40th anniversary reissue album which consists of the original Too-Rye-Aye recordings and all-new production to achieve a sound closer to Rowland’s original vision for the record. Some of the songs sound quite different, but “Come On Eileen” is almost untouched. It was perfect all along.

Em Pasek is a geoscientist and PhD student from Michigan currently residing in the central Sierra Nevada.

chelsea biondolillo: Glued in Golden Snippets [1]: “Pump Up the Volume”

Featuring brief histories of collage, sampling, and house music

The first version of “Pump Up the Volume” was a little over five minutes long, and was known at the time as a “cut up” track—a track incorporating samples mixed by one or more DJs. Cut-up is also a literary term, used to describe writing created from random words and phrases cut from a primary text, the technique, created by French-Romanian Dadaist poet Tristan Tzara (see three poems here, was later rediscovered and popularized by William S Burroughs. Tzara’s poetics were inspired by Cubist collages. Originally called papier collé (literally glued paper) by Georges Braque and Pablo Picasso, champions of the practice, they are generally considered the first occurrence of intentional collage in Western art history.

Figure 1: By Marcus Andrews - Author, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=107683551

That first “Volume” was released to UK dance clubs by the independent label 4AD as a “white label” single—an LP without artist credit—in July of 1987. It was officially issued a month later as a double A-side 12” single, and just one week after that, as a remix, with nearly 90 more seconds of hardcore DJ scratching and samples, and this is the version that matters the most to this essay.

In fact, there are two key remixes of “Pump Up the Volume”—4AD’s UK 12”, and an American 12”, licensed by 4AD to 4th and B’way Records. Depending on which version we’re talking about, “Volume” can serve as a vehicle to tell a story about the evolution of House music or the history of sampling. Both versions owe their existence, however tangentially, to the history of collage.

Against Snobbism and Tittle-tattle [2]

In Herta Wescher’s Collage, a historical review of collage origins from 12th Century Japan to Western Pop Art in the ‘60s, she notes that the first time a Cubist painting included a pasted paper element was in Picasso’s Still Life with Chair-Caning in 1912.

Figure 2: Picasso, Still Life With Chair Caning. 1912.

Before the chair caning, Georges Braque, Picasso’s friend and colleague, had happened upon wallpaper samples, which he began using in studies for paintings, since reproducing the wallpaper by hand was time consuming. He showed his new trick to Picasso, and papier-collé was born.

Figure 3: Georges Braque, Fruit Dish and Glass. 1912. PD-US, https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3111011

In an examination of post-World-War-I collage art, Christine Poggi describes Cubist collages as “an attempt to undermine [aesthetic purity] by allowing elements of mass-produced culture to infiltrate the previously privileged domain of oil painting.” [3]

Around the same time the Cubists were dolling up still lifes with wall paper and musical scores, Dadaists collage artists Jean Arp and Hannah Hoch, among others, were s spinning dynamic compositions using found elements. These scavenged bits and the resulting compositions were in part a rejection of capitalism and the authoritarianism of traditional art values. Chance, chaos, and nihilism are hallmarks of Dada collages.

Figure 5: Hannah Hoch, Cut with the Kitchen Knife Through the Beer-Belly of the Weimar Republic. 1919.

Early collage artists all over Western Europe appropriated text and images from newspapers, books, and magazines, but without media conglomerates to object, their work was generally considered “transformative”—a concept that the US would eventually codify into law.

Appropriating images and audio both became easier after World War II with the commercial introduction of two pieces of technology: photocopiers and magnetic tape. Both allowed for the modification, alteration, incorporation, and replication of the creative output of others. By the late 1970s and early 80s, lowered costs made this technology even more accessible[4].

Put the Needle on the Record

Which brings us to sampling. The first analog tape samples were created with electro-mechanical keyboards like the Mellotron with its dozens of short lengths of tape of pre-recorded instruments. When the keyboard keys were pressed, the Mellotron could create the sound of a flute or violin playing the note [5].

Like the Mellotron, the first digital samplers were huge and expensive, limiting their use to only few big names in music [6]. Later, portable digital samplers like the E-mu SP-1200 (1987) and Akai MPC60 (1988) could allow musicians to create songs without a studio. Sampled drum beats and fills especially saved rap and hip hop producers time and money, similarly to Braque’s wallpaper samples, making production accessible to a wider range of artists.

Figure 6: E-mu SP-1200

But before that, it was South-Bronx DJs in the mid-80s who took sampling into Dada-like collage territory by borrowing break beats from LP recordings to create new mixes during live performances. [7]

One of those DJs, Frankie Knuckles, left New York in 1977 for a gig in Chicago at an originally private gay nightclub nicknamed the Warehouse.

Figure 7: Frankie Knuckles, from https://www.gridface.com/frankie-knuckles-playlists/

DJ Knuckles would spin two disco records at a time and use a drum machine to add electronica inspired four-to-the-floor beats to extended the songs[8]. These Warehouse mixes were shortened to ’house music by local record stores. The first house record sold to the public came out in 1984, Jesse Saunders’s “On & On”.

Chicago house spread quickly, spawning subgenres as it surged toward the mainstream. House started hitting charts in the US in 1986 and from there, it swiftly infiltrated the electronic and soul club music scenes in Britain, Netherlands, Germany, France, Italy, and South Africa.

Figure 8: House at NYC’s Paradise Garage circa 1980s, credit unknown

And it is at this point that it crashed into two bands and a record label.

A landmark of musical cut-and-paste [9]

Ivo Watts-Russell began independent label 4AD in 1980 after becoming disillusioned with the insincerity and exploitative nature of mainstream recording labels and the “amateurish largesse” of early indie labels like Rough Trade. [10]

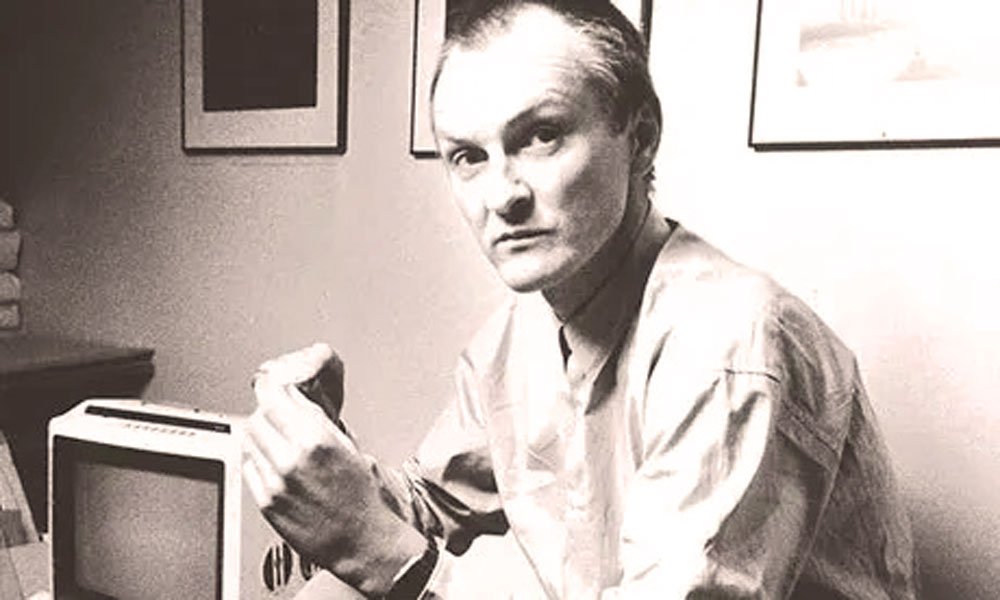

Figure 9: Ivo Watts-Russell in 1988 from arcane-delights.com

Colourbox, an electro / “blue-eyed soul” band, signed in 1982, was nothing like the rest of 4AD’s post-punk, new wave, and art-house catalog.

Figure 10: Colourbox—brothers Martyn and Steven Young

They were also often a pain in the ass for Watts-Russell. Fronted by two quarrelsome brothers, one of whom was notoriously slow at finishing albums, Colourbox crossed multiple genres with their sample-heavy 1983 self-titled EP and follow up full-length (1985), but despite competent digital sampling, sales were disappointing.

In 1987, another act, the self-defined “dream pop” duo A.R. Kane approached Watts-Russell to record an album when their label, One Little Indian, didn’t have the money to do it.

Figure 11: AR Kane's Rudy Tambala and Alex Ayuli

When One Little Indian manager Derek Birkett found out, he stormed 4AD’s offices in a dramatic and often quoted showdown culminating with his screaming, “You stole my fucking band!” To placate Birkett, Watts-Russell signed A.R. Kane for one release only.

That album, an EP, would end up being the first of two “one-offs” that A.R. Kane would record for 4AD. The second was “Pump Up the Volume,” and its B-side “Anitina,” a collaboration of a sort, made at Watts-Russell’s request, between A.R. Kane and Colourbox with scratching and sampling provided by DJs CJ Macintosh and Dave Dorrell.

The name M/A/R/R/S, [11] comes from the first names of the collaborators: Martyn Young (Colourbox), Alex Ayuli (A.R. Kane), Rudy Tambala (A.R. Kane), Russell Smith (A.R. Kane at the time), and Steven Young (Colourbox).

From the beginning, the two groups did not like working together and by the time the single was released, Colourbox was so angry with Watts-Russell for keeping “M/A/R/R/S” on the record despite all but a single guitar part from Ayuli and Tambala having been cut, that it broke the band (though they would resurface for reissues in 2001 and 2012). Watts-Russell was so angry with A.R. Kane for what he described as dreadful behavior that he never released another album with them.

As mentioned at the top of the block, it was the remix of “Volume,” that excited listeners, and that version featured a Dadaist’s dream of unlicensed samples from 26 records including among others Eric B. & Rakim, Criminal Element Orchestra, Bar-Kays, James Brown, Public Enemy, Run-DMC, and regrettably, 7 seconds from Stock, Aitken & Waterman (aka SAW).

Figure 12: Stock, Aitken, and Waterman, looking about as edgy as a watermelon

Those 7 seconds almost led to the first music sampling test case in UK courts, culminating in a 5-day injunction that halted distribution of the record, including its overseas licensing to 4th and B’way Records. After slapstick courtroom testimony and histrionic media interviews, the case was settled out of court for £25,000, which 4AD donated to charity.

But now things get weird(er). Not only was the offending sample’s source track presciently titled “Roadblock” but the sample was also understood at the time to have been sampled by SAW in the first place. The origins of the snippet of singer Chyna and saxophonist Gary Barnacle remain unconfirmed, and both have since been given credits on the track.[12]

Some in the music press accused SAW of calling M/A/R/R/S’s kettle black, since SAW themselves had earlier “borrowed” the bass line from Colonel Abrams’ “Trapped” for one of their own hits. It was also hinted that the whole controversy may have been a stunt to keep said track on the UK charts despite M/A/R/R/S’s swift advance. The track? You won’t believe it.

Adding to the rat king of appropriation allegations, some claimed that the SAW sample in the remixed UK release was itself payback for a remix of Sybil’s “My Love is Guaranteed” produced by SAW’s Peter Waterman and released the same week that the original version of “Volume” was climbing the charts as a white label. The Waterman remix, called the Red Ink mix is… uh, extremely reminiscent of “Volume.”

In the end, the SAW injunction meant that the UK radio edit and all US versions of the song wouldn’t feature Chyna’s “heyyyyy” at 3:11. But that wasn’t the only cut: James Brown’s lawyers were also waiting for the single to hit US soil, so away those went.

All told, the US remix is short over half a dozen of the UK samples. Several were replaced with samples of 4th and B’way artists (eliminating clearance issues). The song’s Wikipedia page includes a “select list”of samples that appear on the 4 UK and 4 US versions. However, there are also multiple music forums that have tried to suss out all the original sources.

Meanwhile, despite litigation, fisticuffs, and hurt feelings, “Pump Up the Volume” raced to the top of charts all over the world, reaching number one in Canada, Italy, New Zealand, and Zimbabwe. It peaked at thirteen on the US Billboard Hot 100.

Figure 13: 4/5ths of M/A/R/R/S—looking very happy to be in the same room—courtesy 4AD

Its success could have been great, but most of the people involved never saw it that way. The single dragged Watts-Russell into the ugliness of big music he’d worked to avoid. After its release, A.R. Kane went on to record albums on other labels, though none came close to “Volume” in reach. Colourbox had initially hoped to tour as M/A/R/R/S, but A.R. Kane demanded £100,000 for the rights to the name which Martyn Young refused to pay.

Figure 14: Pump Up the Volume (movie)

And so, “Pump Up the Volume,” a collage of illicit hip-hop and soul samples and the UK’s first single capitalizing on American House music’s popularity, became a one-hit wonder of epic proportions for three bands. The anthem-ness of it is unmistakable and the beat is infectious. Eric B.’s titular line was even borrowed for Allan Moyle’s 1990 teen-angst-meets-pirate-radio film. In 2020, pop culture magazine Slant ranked it 18 in their list of 100 Best Dance Songs of All Time . Despite its indisputably indie origins, cut-up structure, illicit and combative foundation, and crunchy, soulful cuts, it remains a classic Top-40/dance crossover hit, most popular in my town, anyway, with cheer squads, aerobics classes, and tailgaters.

[1] Taken from a quote by A. Grishchenko describing Russian painter and collage artist Alexandra Exter—1913. From Herta Wescher, Collage. (1968)

[2] From Marcel Janco, Zurich Dadaist

[3] Christine Poggi, In Defiance of Painting: Cubism, Futurism, and the Invention of Collage. 1992.

[4] For more on early sound reproduction, see this very weird bit from the 1979 BBC documentary, “The New Sound of Music”

[5] Something the Casio SK-1 would make available to anyone with $100 in 1985, including my parents who bought one for me.

[6] In 1983, Herbie Hancock demonstrated his Fairlight CMI to Maria and the kids on Sesame Street

[7] from https://www.thomann.de/blog/en/a-brief-history-of-sampling/

[8] There isn’t the space here to talk about the history of disco, but it is worth noting that it was, in part, a response to the isolating consequences of race riots and homophobia in the ‘60s. Early discotheques were often private night clubs, safe spaces, for predominantly gay people of color.

[9] From Michaelangelo Matos, “How M/A/R/R/S’ ‘Pump Up the Volume’ Became Dance Music’s First Pop Hit, Rolling Stone, July 2016

[10] Richard King, How Soon is Now: The Madmen and Mavericks Who Made Independent Music 1975-2005. (2017)

[11] Also stylized as M / A / R / R / S, M /A /R /R /S, M A R R S, M-A-R-R-S, M. A. R. S. S., M.A.A.R.S., M.A.R.R.S, M.A.R.R.S., M.A.R.S.S, M.A.R.S.S., M.a.r.r.s., M/A/A/R/S, M/A/R/R/S, M/A/R/R/S., M/A/R/R/S/, M/A/R/S, M/A/R/S/S, M/a/r/r/s, MARRS, MARS, Maars, Marrs, Marss, and The M.A.R.R.S. (https://www.discogs.com/artist/12590-MARRS)

[12] Hear the extended version here, including Chyna and Gary in the first 3-10 seconds of the song and again at 3:05-12.

Chelsea Biondolillo is the author of The Skinned Bird: Essays and two prose chapbooks, Ologies and #Lovesong. In the summer of 1987, she was 14 years old and not even remotely cool enough to know about house music, but she went to her first real dance party right around that time, on the campus of Central Michigan University.