round 1

(16) king’s x, “dogman”

upended

(1) soundgarden, “fell on black days”

679-402

and will play on in the second round

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on March 6.

The Black Days Never Go Away: Thoughts on Chris Cornell, Depression, and Suicide; Joshua E. Borgmann on “fell on black days”

I.

On May 14th 2017, I spent the day at an amphitheater near Omaha, Nebraska pumping my fist, throwing up “devil horns,” occasionally moshing, and banging my head through an outdoor music festival blandly named Rockfest. I’d come to see some early acts such as the Dillinger Escape Plan who were on the heavier side of this festival. While I enjoyed a few of the softer bands like The Pretty Reckless, I had to suffer through the tired modern rock of co-headliners Papa Roach before I was finally reward with what I had come for all along, grunge legends Soundgarden. I’d seen the band once before in the late 1990s when they were on the verge of breaking up for the first time.

While I’d enjoyed that show, I’d felt that something had been missing. They didn’t seem to have the chemistry and energy that I had expected. I hoped that twenty years later, they would deliver something better. I was not disappointed. The band ripped into classics like “Outshined,” “Rusty Cage,” and “Fell on Black Days” with the precision and power befitting their much-deserved status as legends. Above it all, vocalist Chris Cornell delivered on every note. I felt as if I were standing there in 1994 rather than 2017. It was an experience I had waited twenty years for, and it turned out that it was something that I would never have the chance to experience again. Four days later, On May 18th 2017 after playing a show in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, Chris Cornell committed suicide at the age of 52.

II.

Soundgarden came to fame as one of grunge’s big four with Nirvana, Alice in Chains, and Pearl Jam. Most fans discovered the band after Nirvana had started the grunge craze with Nevermind. I, however, had already discovered 1989’s masterpiece Louder Than Love, which put its hooks solidly into me with its collision of Black Sabbath inspired riffs and Cornell’s soaring vocals that evoked Robert Plant. When Nirvana and Alice and Chains hit it big a few years later, I was firmly planted in the grunge fan base. I’d already been fully indoctrinated into the world of rock music after a brief foray into rap.

I turned sixteen in 1990, so I grew up in a musical landscape transitioning from “hair” metal to rap, grunge, and thrash metal. Each of those genres played a profound role in my musical development that I’ve never really deviated from. “Hair” metal had been there to fuel my teenage dreams and has largely defined what I came to view as success aka partying, lots of money, and being successful with women. “Hair” metal is probably the reason that the only thing I’ve ever really wanted to be was a rock star; however, the dream that “hair” metal presented was one that was a million miles from my reality as a broke loser who always struck out with the opposite sex. Grunge, on the other hand, provided me with anthems likes Alice and Chains’ “Sea of Sorrow” and Soundgarden’s “Outshined.” Songs that related to what I was feeling, failure and utter life crushing hopelessness.

III.

A part of me struggles with why someone like Chris Cornell would commit suicide. I’ve had similar thoughts after the deaths of other celebrities who seemed to have it all like Robin Williams or Anthony Bourdain. I would literally sell my soul to have the life of some one like Chris Cornell or Anthony Bourdain. They were out there traveling the world experiencing the very nectar of life and being loved by large fan bases. They had money, the attention of beautiful women, and in a more mundane sense successful family lives. I, on the other hand, moldered away at a job teaching at a community college, barely managed to pay my bills most months, struggled through a marriage to the only woman that I’d ever seriously dated, and failed miserably at my attempt to be father to an adopted son. I was (and am) constantly broke, oppressively lonely, and chronically depressed. However, I told myself as I’ve done every single day that I was depressed because I didn’t like my life circumstances. I told myself that if I had a life like Chris Cornell or Anthony Bourdain, I would be happy. I wouldn’t be depressed. I don’t know if there is any truth to that idea. Certainly, the part of me that is extremely extroverted and craves attention and adoration would eat up that kind of life. It’s probably the only kind of life that would give me anything close to happiness; however, I can’t be certain that the dark thoughts would go away.

For all my pretending not to understand why a man like Chris Cornell would die by suicide, the truth is that I know why because the only thing that separates me from men like Cornell and Bourdain is that they were rich and famous men with suicidal thoughts while I’m just a nobody with suicidal thoughts. Even that is merely a matter of perspective, an outsider looking at my life might see a successful professional and published author with several advanced degrees, a solid job, a long-term marriage, a home, cars, and even a bunch of published stories. Such an outsider might say that I have a pretty good life, and I can see why they would say it. However, I look at the same life and see abject failure. This is how depression works.

IV.

Soundgarden’s “Fell on Black Days” expresses many of the feelings that I experience on a daily basis. Two passages in particular seem particularly in tune to my emotional state. The first is the opening of the song:

Whatsoever I've feared has come to life

Whatsoever I've fought off became my life

Just when everyday seemed to greet me with a smile

Sunspots have faded and now I'm doing time

Those first two lines encompass the struggle that is depression and mental illness in general. The heart of depression is the thing that we fear, the thing that we fight against; however, it is all too often the case that no matter how hard we fight it becomes our lives. We simply cannot escape it.

When Cornell sings, “Just when everyday seemed to great me with a smile, sunspots have faded,” I’m reminded that I’ve experienced this feeling so many times. I feel like my life is on the upturn and that where I’m headed I’m finally going to be good, but then something happens, and I find myself back under the thumb of those old negative emotions. Sometimes, these are small every day things like a charge going through the bank that wipes out the ten dollars that I was going to buy some Mexican food with, and other times it might be adopting a teenager and thinking that I have a new happy family only to quickly realize that the teen and my wife utterly despise each other and that I’m in for six years of being stuck in the middle of an unending war between them. The truth is it doesn’t matter if it’s the small thing or the large thing that hits because the “black days” are back, and I once again feel like I’m doing time.

The idea of “doing time” is a constant refrain throughout the song, and it’s a perfect metaphor the way that I experience depression. When I look at the world, I don’t see the endless opportunities to improve my situation, or if I do, those opportunities seem inaccessible…too hard. What do I see? I see an endless stream of days that will be exactly the same as the one that I’m stuck in right now. I’ll hate everyone of these days just like I hate the day that I’m in, but I’ll keep doing time by going to work, coming home, struggling through a conversation with my wife, and sitting alone on my couch without a friend to talk to or comfort me. In my mind, this is all that there will ever be, and I’ll simply continue doing it as I wait to eventually die. Life is no longer living: It is waiting to die.

The second versus goes on to add another feeling that seem all too familiar to me when Cornell sings, “Whomsoever I've cured, I've sickened now, and whomsoever I've cradled, I've put you down.” While the line is certainly open to interpretation, I relate what he’s saying to the sense that whatever I touch goes bad. I’ve felt like this for a long time. In fact, I’ve often said that if I believed in God, I’d believe that he had put a curse on me. I simply feel like whatever comes into my life is destined to end in failure. Again, this can be anything from a material possession to relationships. Most of my friendships have ended poorly. My marriage has not gone as expected. My attempt at fatherhood was a complete failure. My writing career has not brought me the success I craved. While many of these things are shaped by outside factors, I never see them that way. They are all signs of my failure and that I break whatever I touch. I’m a destroyer…not a creator.

Of course, everything cannot turn out bad; however, when it doesn’t, I simply chalk that up to accident or pure luck. When I get complimented on a job well done, I feel bad because I believe that I should have done better, and I probably half assed my way through it and don’t really deserve the praise I’m given. It cannot be possible that I’ve truly done well. In many ways, it feels like another line from “Fell on Black Days”: “I’m only faking when I get it right.”

V.

Listening to Soundgarden’s music, especially the rest of their masterpiece Superunknown, makes it easier to understand Cornell’s suicide. Superunknown is a beautiful album blending some of the band’s heaviest material with a few more low key moments. Kim Thayil’s riffs are doomier than ever constantly bring to mind early Black Sabbath, but at the same time, he’s constantly working in more melodic moments and even taking some time to drop some bad ass shredding. The album displays a great deal of variety, yet holds together as a complete album in a way that most modern albums simply do not. One of the unifying elements is the sense of lyrical darkness that is carried from song to song. Crushing tracks like “Limo Wreck” and “4th of July” may seem darker the melodic “Black Hole Sun,” but as pretty as that song may seem, the lyrics are as dark as the black hole that it references. However, Cornell’s vocals are so beautiful, so glorious that we forget that he is straight up telling us just how hopeless life can seem through the eyes of a depressive.

When I was younger and in the depths of my darkest days, I’m not sure I totally appreciated the artistry of Superunknown. I was caught up in Badmotorfinger’s “Outshined,” “Rusty Cage,” and “Jesus Christ Pose.” It took me a decade to truly realize that Superunknown was the real masterpiece, and that it was far darker than it seemed. In the end, it is that darkness that kept pulling me back to grunge especially Soundgarden and Alice in Chains. I found the other kinds of darkness in a lot of heavier music, but for true, dirty, trauma soaked hopelessness few albums can top Superunknown or AIC’s masterpiece Dirt.

VI.

Considering that Soundgarden had a hit single named “Pretty Noose,” I can’t say that I’m surprised that Cornell’s death came via hanging. I’m also not surprised that the noose was the means that Anthony Bourdain, Robin Williams, and a slew of other celebrities used to end their lives. Honestly, I understand because I’ve literally been there many, many times. I’ve suffered from depression with suicidal ideation since I was twelve years old, and I’ve found my neck in a noose hundreds of times in those thirty-four years. The vast majority of those times took place in my teens and twenties, but the noose still holds a certain sway over me.

I think I was in my mid-thirties before I started to think that it might be more likely that I die from a heart attack than suicide. Before then, I had little doubt that I would die by my own hand. It was a foregone conclusion. Perhaps, it shouldn’t have been because I’d been romancing the noose since I was twelve and never fully given in. However, it was hard to ignore the countless times I chocked myself with a belt hanging in my childhood closet, or the times that I tried to hang myself from the cross beams in my garage, or that one time that I tried to hang myself from a stair railing at outside a church near my house. That time I used an electrical cord which broke. Most of the other times, it was a belt, and I simply let myself get a little dizzy and then gave up.

While I was certainly depressed and claimed that I wanted oblivion, I think that there was a certain thrill in pushing things that close to the edge. I had romanticized death. However, death wasn’t really what I was looking for. I knew even then what is true of most people who think of suicide. I didn’t really want to die: I simply didn’t want to live the life that I was living. While I might not be playing with nooses as much these days, I’m still at a point where I don’t want to live the life that I’m living, so darkness always has a way to keep creeping in.

Now, this is no cry for help. I’ve been in therapy for fifteen years. I’m constantly working on myself and dealing with my depression. I’m simply saying that the darkness doesn’t really go away. My life might be better than it was when I was twelve, but it still isn’t the kind of life I want. If Chris Cornell has taught me anything, he’s taught me that the no matter how good life might seem the darkness may never go away.

VII.

Soundgarden opened the door to grunge for me, and aside from Alice in Chains, they remain my favorite band from the period. Grunge sucked me out of the fantasy world of “hair” metal and gave me a bleak soundscape that fit a teenager like me. I needed that because I was never supposed to be anyone. I was the kid that was abandoned by his mother at two and literally given away by his father a few months later. Even after my great-aunt adopted me, I was abandoned again when she dropped me permanently at my great grandmother’s house. I grew up there in a home that by my teens was literally not fit for human habitation. I dealt with the snakes and termites in the bath tub and the huge whole in the floor near the washing machine the way that most people deal curtains being not matching the wallpaper. I dealt with the influx of aunts, uncles, cousins, and even my adoptive parents into my great grandmother’s house each time they were evicted or got out of jail for a short time. I was written off as special education kid who couldn’t even learn the alphabet by the time I stepped foot in kindergarten. Even when I surprised the school and turned out to be an ace at taking standardized tests, I was told by at least one guidance counselor that people like me didn’t go to college. Of course, she was mostly right because no one else in my generation even graduated high school let alone went to college. I was the kid who was beaten every day by his classmates. The kid that was told that he was unlovable because he was fat and hideous. The kid that believed that he was in fact unlovable because he was fat and hopelessly ugly…the man that pretty much still believes that. I was supposed to burn out and end up fixing cars between sucking down cheap beers, but I didn’t end up that way. Oddly enough, I give a lot of the credit to the fact that grunge and other heavy music motivated me. I found something to relate to and decided that I might always be a white trash outsider, but a white trash outsider didn’t have to be what the world told him to be.

Unfortunately, while I’ve made it through the last thirty-four years, the vocalists of the four grunge bands that most inspired me have not. Cornell and Cobain were both suicides, and Layne Staley and Scott Weiland essentially killed themselves via addiction. I miss all of them and wish that they were still here to make more music. I often wonder what Cobain could have accomplished if he had lived past his twenties, and as much as I love new Alice and Chains records, I can’t help wondering what could have been with Layne. Still, Cornell’s death perhaps hit me the hardest because I saw him just a few days before. He never seemed better, and then he was simply gone.

Josh bio

To Be a Good Man: Patrick Madden on "Dogman"

Dogman (song)

From Patrick Madden, the free essayist

|

|

This

essay is hopelessly biased beyond the possibility of impartiality.

Indeed, its author does not even attempt to hide his blatant

subjectivities, as if he doesn't believe in an objective

worldview. Please help resolve this issue by giving "Dogman"

your March Plaidness

vote.

|

| "Dogman" | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||

| Single by King's X | ||||

| from the album Dogman | ||||

| Released | 1994 | |||

| Recorded | Southern Tracks (Atlanta, GA) |

|||

| Genre | Grunge / Hard rock | |||

| Length | 4:01 | |||

| Label | Atlantic | |||

| Songwriters | Jerry Gaskill, Doug Pinnick, Ty Tabor | |||

| Producer | Brendan O'Brien | |||

| Influenced | AiC, STP, Pearl Jam, Soundgarden, etc. | |||

| King's X singles chronology | ||||

|

||||

"Dogman" is a kickass grungy song by the underrated and underacknowledged American band King's X. It was released as a single in support of their 1994 album Dogman.

Grunge

As a noun, nothing pleasant: filth and grime, repugnance and odiousness; a "word used in TV commercials about scum on your shower curtains" (according to Soundgarden bassist Ben Shepherd); backformed from grungy, itself perhaps combined grubby and dingy. If not quite onomatopoetic via sound, then perhaps by feel?

But as a musical style and attendant culture, a kind of anti-revelation: discordant, distorted guitars; lackluster vocals; melancholic lyrics; "artless" live-like production. Grunge is unflashy, dispassionate, ironic, apathetic, everything '80s pop (and hair metal) was not. And despite the variety of styles coming out of Seattle in the late '80s, even on SubPop Records, once the marketers got hold of the label, grunge became what sold.

Essentials

For Doug Pinnick, King's X's bassist and most-time lead vocalist, it all comes down to one simple thing: the guitar's (and bass's) low E string tuned down to D. "Grunge, to me, is drop-D songs. It's not Seattle. The whole world drop-D tuned within a year…" And this, more than any regionalisms or individual musicians or producers or executives, led to the explosion of so-called grunge (and adjacents) in the 1990s.

Personal Life

Lehi, Utah, and Los Angeles, California, 2021

I decided to have a chat with Doug. It had been over a decade since I'd seen him, nearly three since we'd had any kind of regular contact. I was nervous, but I needn't have been. He readily agreed and, when he Zoomed in, greeted me warmly, recalling past conversations and correspondences as if we were old friends, which I'd dared not claim, but which he readily acknowledged. "Those letters I wrote…" he said, "they never were letters of 'I'm Doug Pinnick, a rock star and this is a fan.' It was always, 'this is my friend'… it's a friendship thing. … Friendship is way better than being a rock star."

Grunge

Origins

| Song | Band | Year |

|---|---|---|

| Dear Prudence | The Beatles | 1968 |

| Moby Dick | Led Zeppelin | 1969 |

| Cinnamon Girl | Neil Young | 1970 |

| Ohio | Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young | 1970 |

| Black Water | The Doobie Brothers | 1974 |

| Fat Bottomed Girls | Queen | 1978 |

| Drop Dead Legs | Van Halen | 1984 |

"The quickest way to get a whole generation to change the way they're playing is to do something that any kid can pick up his guitar and play immediately," says Doug, crediting Limp Bizkit's Wes Borland with the idea, and I believe them. I suspect nobody can really tell me who "invented" drop-D (such a slight variation from standard EADGBE tuning, in which the low E string is flattened a whole step to a D, thus allowing "flat fingered" barring on the lowest three strings, producing a ready power chord), but a bit of superficial research reveals that this simplest of variations has long been used in blues and bluegrass, and it appears on plenty of rock songs long before the '90s.

King's X and Soundgarden, 1988

Despite my just mooting the question, Doug makes a pretty good case that King's X's debut, Out of the Silent Planet, ushered the style into much more widespread use than before. "We came out with Drop D tuning in '88, and Soundgarden came out in '88 with Ultramega OK. Our record comes out, same time [King's X released their album 7 months before Soundgarden, in fact], never heard of each other. I think when both of our bands [recorded in drop D]—we did a whole record like that; they only had one song ["Flower"] like that…" Doug trails off, but his point is clear, that these albums began something that would soon catch on.

"When I talked to Kim Thayil about a year ago," Doug continues, "he told me that he introduced Chris [Cornell] to drop D tuning in '85. But they didn't really write anything. And Ty [Tabor, King's X guitarist and second-most-prominent-lead vocalist] wrote 'In the New Age' in 1985. And he said, 'This is bluegrass tuning. I just wanted to do something that I felt like was what I'm going for, like Beatles metal.' Whatever that muse was, he was talking to Ty and he was talking to Kim. I believe the muse had to talk to those two guys to tell us, because me and Chris took off and ran with it. When we both heard the drop D tuning, seems like almost everything we wrote had something to do with that; it started happening at that point. A lot of our songs became similar. 'Black Hole Sun' sounded like a King's X song. 'Outshined': people called me up and said, 'Dude, Soundgarden's ripping off King's X again.' There were a lot of similarities. Not to say he was copying us. What I'm trying to say is we were pushing each other without knowing. When I was introduced to drop D tuning, it just opened the whole world up."

It seems futile, honestly, to seek the kind of "credit" so many people are interested in locating with this or any other question of originality, a fact that Doug readily acknowledges ("A lot of us who were 'innovators or inspirational,' we're the ones who didn't get the glory or the money; it really humbled me and helped me realize that we still are a part of this.") But we should all acknowledge, as have so many musicians in so many of the wildly popular "grunge" bands, that King's X, musicians' musicians all, were right there in the early mix, beloved by and influencing others.

Personal Life

Notre Dame, Indiana, 1990

Imagine with me this scene: a young man in red plaid jacket and scraggly hair trudges across the frozen fields south of campus toward the record store. His friend, now graduated, has written him recommending a band he describes as "hard rock with a conscience." The young man sometimes feels alone, especially now that his friend, with whom he would play cards and listen to music and make silly faces, has gone. He would not admit this. Often he sits on his floor and plays his records, studying the liner notes, singing along, abiding in melancholy. When he finds the CD in the stacks at Tracks, he's intrigued by the ornately "carved" biblical stories in the block letters of

FAITH

HOPE

LOVE

and the blatantly metaphorical daisy poking out of a vast, dry, cracked landscape on the back cover. He lays down his $12, then trudges back to campus. As he sits on his dorm room floor and unwraps the King's X CD, places it in the player, presses PLAY, he understands viscerally that he has found exactly what he has been looking for, without quite knowing it.

Grunge

Seattle, 1988

Without claiming too much, offering that this is what was reported to him, and you can believe what you want to believe, Doug recalls the band's visit to Seattle in support of their first album. The venue was "really small," he says. "I looked out the back door and you could see the bay. We played for like 30 people. And you know what we sounded like, … so I know that we impressed them, but I didn't think that they liked us. Well, about a year later, I remember coming home from the road and I turned on Headbangers Ball, and every band was drop D tuned except Bon Jovi. And I went 'what in the world has happened?'"

What had happened may have been what Richard Stuverud, the drummer, later reported: "'Hey, Doug, you know, every band in town was at that show.' Nobody went to see bands in Seattle but people in bands, because nobody cared. All the bands would go if it was a national act. So, basically, we played for a house full of musicians. A lot of those guys in a lot of those bands."

Maybe you already know this, about drop D, or maybe you only notice a general low-key vibe in the popular music around the turn of that decade, but for confirmation, here's Rick Beato, a former producer and current YouTube musicologist, recalling that "I was in drop D…for years. My guitars were only tuned in that tuning, because every heavy band from the early '90s through 2012… almost all their songs were in drop D."

Personal Life

Whippany, New Jersey, 1991

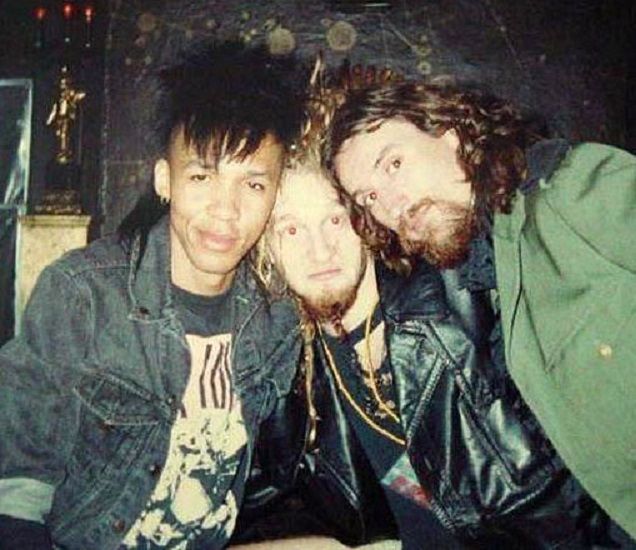

(L to R: Pinnick, Gaskill, Tabor)

This was before cell phones, at least for me. I was working as a janitor at the sprawling AT&T campus down Whippany Road, which work afforded me plenty of time for reading and listening to the radio. All month I'd been calling into WDHA for entries into a drawing to attend a special King's X acoustic breakfast show at the Catalina Bar & Grill in Cedar Knolls, giving the phone number for my boss's office. As I packed my things to go home for the day, disappointed that my name had not been announced, the phone rang. Because some of the winners couldn't make it, I was in. My friend Joe and I (two halves of our unsigned band The Tords) arrived at 8 AM the following Monday to find Doug Pinnick, Ty Tabor, and Jerry Gaskill eating breakfast around the bar, a bit shy but generous with their time to chat, sign autographs, take pictures. We found them to be humble and friendly, utterly egoless, unhierarchical. As they sat down on a six-inch riser to play, amplified but just barely, effected only minimally, Joe and I sat cross-legged on the floor in the front row, awash in the lush grooves and angelic vocal harmonies, smiling from beginning to end at the tightness and innovation of the sonically naked three-piece in front of us.

Genuineness

When I was young(er) and foolish(er), more susceptible to fawning obsequiousness, I wrote earnest letters to Doug and he wrote back, generously and genuinely, sometimes including bootleg cassettes of live performances (Woodstock '94, etc.) or demo tapes, once sending a selfie (pre-digital, holding a red point-and-shoot over his eye in a mirror) after he'd braided his signature Mohawk. After every show, he and Ty and Jerry would appear in the parking lot or alleyway next to the venue to visit with fans, sign autographs, take pictures, as many famous folks do, I suppose, but over the years it became clear that Doug was remembering people, asking followup questions, having real conversations, keeping up with our lives. Once, I met three members of Dream Theater after a show, when they gave their new CD (Images and Words) to Ty. Once at a show in Manhattan, I caught Will Calhoun of Living Colour as he stage dove during "Moanjam." At that same show, same song, for reasons unknown and unknowable, my neighbors cleared out when Mark Poindexter of Atomic Opera dove off the stage, leaving me alone to absorb his momentum. To the floor we both went, and with a "sorry!" and a hand to help me back to my feet, he was gone. After the show, in the alleyway next to The Ritz, I overheard him telling a friend, "I tackled a poor guy!" and I sidled up to say, "That guy was me!" Once I arranged with Doug to attend the soundcheck for their Long Island show, and I brought along my younger brother and his two friends. When we discovered that it was an over-21 show only, Doug talked with the venue's management and got us all in anyway. Once, after I'd been gone on a Mormon mission for two years, missing the Dogman album and tour entirely, I went to a King's X show in Philadelphia with that old friend whose letter introduced me to the band years before. During a vocal break in the opening number, "The Train," Doug scanned the crowd and, eyeing us a few rows back, said, "Hey, Pat!" with an enthusiasm so genuine that even my friend, whose name is also Pat, felt it, and I remember it warmly to this day.

Dogman (song)

The result of a Lennon/McCartney-like musical rivalry, and a devastating break with their long-time manager, whose financial finagling left the band with nothing but their name, "Dogman" (the song's title was also used for the album) comes from a time of anger and uncertainty. Ty Tabor, who wrote the song, says that "it's kind of disjointed artistically, on purpose, and trying to express that feeling of not standing on solid ground… The thing is, I write lyrics because I don't know how to explain what I'm feeling. "

Ty's original demo used "to be a good man" for the chorus, which he and everybody else in the band knew wouldn't fly, but I still believe in that underlying sentiment whenever I hear it. The replacement phrase "to be the dogman" is typical King's X ridiculousness (see Gretchen Goes to Nebraska or "Charlie Sheen" or Ogre Tones). According to a Doug Pinnick interview at Songfacts, "Whenever King's X has an artistic decision to make, if we can't come up with anything, whoever comes up with the stupidest thing, we'll go for." Doug remembers that after everyone tossing about plenty of colorful adjectives, he threw out "let's just call it 'to be a dog man,'" and the phrase brought new peals of laughter and band agreement.

That's one of the things I love about the song: its juxtaposition of the solemn and the inane, the jumble of images from light bulbs to powder to books to horse races to business luncheons to "leaves in need of raking," suggesting poverty and prayer and pain and depression, instabilities and vertigos that the driving guitar, bass, and drums confirm and complicate.

(unknown date, venue)

Musically, the song came from Tabor and Pinnick's friendly competitiveness, "like two guys in a race," Doug describes it, "trying to write the best, baddest, biggest tune." And he's proud of the results: "I feel like we came to a place where we kind of understood what was going on with the King's X sound. We were very angry by how we were manipulated by [our previous manager]. We wanted to be that band that slammed you in the face like we were live. Ty said he wanted to write the baddest-ass riff he ever wrote in his life, and it is, probably one of the best riffs ever, in my opinion, and I'm jealous of him, because I wish I had written it." Drummer Jerry Gaskill remembers that the band wanted the record "to be so heavy that it sounds like big monster creatures are walking through the town, and they're crushing everything." Nuno Bettencourt, of Extreme, writes that "when I hit play on ...Dogman, I nearly drove off the road I was so pumped." Mick Mars, of Mötley Crüe, says that "my favorite [album] is Dogman." Jeff Ament, of Pearl Jam, recalls of this period that "[King's X] were one of my two or three favorite contemporary bands at the time." While I've got you here, let me add that Andy Summers, of The Police, said " I think they’re easily one of the best rock trios anywhere. I don’t think they’ve been equaled." And Billy Corgan, of The Smashing Pumpkins, believes that "They were really ahead of their time. If you listen to the music that followed, they really figured things out that took many bands ten more years to figure out." (You can find these quotes and more in King's X: The Oral History by Greg Prato.)

Personal Life

Lehi, Utah, 2021

of King's X memorabilia

I've discovered (once again) that it can be uncomfortable to revisit one's past self. In my case, to find some of my awkwardly fawning letters, to see evidence of my obsession played out in a stack of photocopied articles and interviews, dozens and dozens of bootleg tapes and CDs, many of which I made myself with colorful inserts and liner notes, and to realize that although I still have this cache of King's X memorabilia, it's been sitting in a box at the back of the closet under the stairs for nearly two decades. So much of what was once essential to me is now just an asterisk. Which is not to say that I'm embarrassed by the music or my enthusiasm for it (I'm still a fan; I still listen intently and feel inspired, and not just for nostalgic reasons), but by my approach to it. Or maybe I'm simply realizing that what was once so important is now only ancillary, and that I cannot quite access the ways these influences have played out in my life (and yet here we are, bringing my musical obsessions into my writing). All this is well and good. Then I was single and shielded from serious responsibility. Now I am a husband and father (to six children) with a rewarding and time-consuming job, so thank goodness I no longer have time to create and distribute a monthly King's X fan newsletter. And it brings a strange kind of hopefulness to return to all these relics and to try to reconnect with such an earnestly invested past self. That guy was sure a nerdy ingénu, but he was unabashedly enthusiastic and sincere. Sometimes I miss him.

Influence

(unknown date, venue)

There's an inevitable argument inherent in this essay, despite my wishes to avoid it (because it's been made so many times before, to no avail; because it's too late; because questions of credit and originality are inescapably convoluted; etc.): that among the infinite converging factors that gave rise to the woolly thing we recognize as "grunge," King's X was central, particularly with their first few albums, though they were never quite invited onto the bandwagon that parted from Seattle in 1991 to conquer the world. So it's fruitless to make bold claims, or to ignore the circling swill of influence that was this particular time in American music. Influence never flows only one way anyway. Doug readily admits to rushing right out to buy the first Alice in Chains EP; to chatting/plotting (about crooning!) with Chris Cornell during the recording of Dogman and Superunknown; to wishing King's X were invited along the Lollapalooza tour (but Perry Farrell, as reported by one of his bandmates, thought King's X was "pretentious bullshit"); to believing that King's X were "too spiritual and Christian and pretty" for the scene, like "the Bee Gees" with their gorgeous vocal harmonies; to putting on a prerelease copy of Alice in Chains's Dirt and discovering "everything that I wanted King's X to do, be, and sound like. I was so disheartened that I couldn't play side two" (meanwhile recalling a story about Layne Staley running down the street after Jerry Gaskill to joke "Keep writing great songs so we can keep stealing your shit").

"They were like my kids," Doug muses (having just turned 70 last September, while most grungers are somewhere in their 50s now). "They looked up to me; they had this innocence about them. From the day I met them all, they were respectful." Maybe that's the word: respect. Not credit or influence, not a fruitless argument about who came first with what new thing. But mutual respect among people caught up in this unexpectedly popular musical movement.

Pre-rock

It's worth mentioning, if only briefly, that nothing is created ex nihilo, and musical genres and subgenres come not from individual geniuses in isolation, but from recombinations of past works passed through and reformed by multiple consciousnesses. In the case of King's X, some of these include utterly un-grungey Sly and the Family Stone, Curtis Mayfield, Yes, Led Zeppelin, Chuck Berry, KISS (this list is shamefully shorter than the one Doug would provide), and even the Andrews Sisters, whose "Boogie Woogie Bugle Boy" inspired similarly tight vocal harmonies on "We Were Born to Be Loved." Having grown up in the 50s, at the birth of rock and roll, Doug appreciates so many musical styles that it is nigh impossible to unravel and trace the various threads of influence on the sounds he, with others, now creates.

Form

I have tried to remind us of the incredible, ineffable complexity of interrelations by writing this essay in the form of a Wikipedia article, to suggest, via links and collaboration and eternal internal incompleteness, that everything is connected, that nothing is original (nothing is origin, nothing self-evident, nothing primely moving). We recognize the fonts and arrangements, despite this new venue here at March Plaidness, and we are keen to discern how the author has played within and worked against our expectations for the thing we know, how he has conformed to and subverted the form, and how those choices contribute to meaning.

"Everything I've ever done in my life," says Doug, speaking of his myriad varied influences, "I put my own twist to it, I try to be outside the box. Everything I write, I try to take it outside the realm somewhere. I still want to find something in there … that makes you move, that makes you go 'I never thought of that before.'"

I really do believe that King's X is a major node within the site map of grunge, and the song "Dogman" an example of the band circling back to become what it had influenced others to be. And while claims such as this may evoke agreement or disagreement, provoke deeper thinking or dismissal, I want again to send us outward, to glimpse the big picture, maybe even blur our vision a bit, and float free from argument, feel grateful just to be here.

Audience

— Charles Lamb "New Year's Eve"

I'm writing this essay amidst and against various assumptions about my audience, starting with the split/combination of song and essay. Is this March Plaidness competition about the music or the writing? Do site visitors click through to watch the videos? Do they read the essays? Are they fans of King's X here to support their favorite band? Are they friends of mine cajoled here by my request? Are they long-term participants in the March Xness tournaments who enjoy reading and learning about new songs or revisiting old songs they haven't heard in a while? Are they seven-year-olds responding without guile? Will they recognize in my essay the same old story they've read so many times before, about how King's X doesn't get their due, how they were supposed to make it big but never did? (Vernon Reid, from Living Colour: "I feel it's only a matter of time before that band is the biggest band in the world.") About how the world is not just?

Repeating Himself

It occurred to me as Doug and I spoke that the poor man is relegated to repeating the same stories and same explanations he's shared hundreds of times. In the old days, when information was more localized in newspapers, on radio shows, this was an appropriate way to spark interest or satisfy curiosity in different places (ahead of a concert, for instance). But with the rise of the internet and the dispersion of ubiety, to the nth power amidst a pandemic, everybody with enough interest in a subject seeks out (or is presented with, by the algorithms trained to train us) the same information no matter who does the interview, no matter where they're sitting during the conversation. Doug is good-natured about all this repetition, perhaps with a peripheral thought about promoting the band, but more prominently with that same genuine interest in talking with a friend, sharing stories, marveling at how things have gone, grateful for the journey's unexpected and even disappointing meanders. "People think that we're hurt, or feel bad about everything that happened," he says. "I wouldn't change a thing. Not a thing. Because I wouldn't be the person I am today, and I'm finally OK with me. The other thing is, there's a lot of people in my life that I wouldn't know and would never have met and loved, and gotten so much love from. To know that that wouldn't have happened… I'm all good."

In conclusion

I'm tempted to invoke Jack Handey's "Deep Thought" about

If you're traveling in a time machine, and you're eating corn on the cob, I don't think it's going to affect things one way or the other. But here's the point I'm trying to make: Corn on the cob is good, isn't it?

which always comes to mind when I've been taking our thoughts away, thinking about other days, writing about who knows what and the kitchen sink, and suddenly I want to wrap things up? Who do I think I am? But really all I want to say is how much I love, genuinely love, this band and this man, whose music and personal generosity have meant so much to me, not in an ironic, disaffected way, but as somehow central to the person I wanted to be and, in some small measure, became. Which may be precisely the attitude, and the reason, that prevented King's X from ever making it big. But they're still around, still making music, still taking the time to be part of our lives. So there's that.

External Links

- King's X official website

- "Dogman" live on the Jon Stewart Show

- "Dogman" live at Woodstock 94

- David Cook, American Idol runner-up, covers "Dogman" (w/ Jerry Gaskill)

- Ari Koinuma explains "Why ['Dogman'] Hits So Deep"

- All clips from Patrick Madden's 1/14/21 interview with Doug Pinnick

- March Plaidness contenders

- Criminally overlooked awesome songs

- Unrecognized geniuses

- Influence sponges who generate utterly vibrant and new sounds

- Sine qua non of grunge

- Humble, friendly people who don't let fame get to their heads

- Everybody's influence

- Everybody's friend

- Musicians' musicians

- Finding contentment in the little and the local

- ESSAYS!

Patrick Madden and Doug Pinnick of King's X after a concert, 1992

Patrick Madden, author of Disparates, Sublime Physick, and Quotidiana, agrees with Pearl Jam's Jeff Ament that "King's X invented grunge."