round 1

(2) Pet Shop Boys, “Always on My Mind”

took out

(15) Sufjan Stevens, “Holy, Holy, Holy”

214-86

and will play on in the second round

Read the essays, listen to the songs, and vote. Winner is the aggregate of the poll below and the @marchxness twitter poll. Polls closed @ 9am Arizona time on 3/7/22.

dan kois on pet shop boys’ “always on my mind”

In an apocalyptically abandoned railyard, two men brood in leather and fog. One, wearing aviator sunglasses, sits on an oil drum, hands on knees, head cocked just so. The other stands in silhouette, playing a synthesizer, intimidating in military cap and collar. Smoke billows everywhere. All is red, red as a sunset, red as the inside of a heart.

In 1987 the Pet Shop Boys agreed to perform at a televised tribute concert dedicated to the music of Elvis Presley. The duo, fresh off the success of “West End Girls,” were no fans of the King—well, Chris Lowe allowed, he appreciated Elvis’ “bloated Vegas period”—but saw the opportunities manifest in appearing on television across the U.K. As chronicled by guru of cover songs and tribute albums Ray Padgett, when their manager delivered a pile of Elvis cassettes with instructions to choose a song, the Pet Shop Boys picked the first track off the first tape they heard, simply so they wouldn’t have to listen to any more.

That song was “Always on My Mind,” a B-side recorded by Elvis right around the time his marriage with Priscilla was breaking up. Much more popular than Elvis’ version was Willie Nelson’s mournful 1982 country No. 1, which replaced Elvis’ orchestral bathos with piano and pedal steel, but which still ended with Willie leading a glorious chorus of angels. The Pet Shop Boys’ acid house-inspired cover felt similarly redefining, especially contrasted with the likes of Meat Loaf singing “American Trilogy” on the television tribute’s retro diner set.

The group released the track as a single shortly afterward, and the song went to No. 1 in Britain. In the U.S., “Always on My Mind” was packaged as a CD single and shrink-wrapped alongside some copies of the Pet Shop Boys’ 1987 album Actually. That’s how I first encountered it, when for my 13th birthday my parents bought me a CD player and my brother bought me Actually.

In an unguarded moment years later, my brother, five years my senior, told me he chose the Pet Shop Boys because he suspected I was gay and hoped the album might help me on that journey. I can see why he might have thought that. I was artsy, finicky, unathletic. More than that, I was sharp-tongued and witty, and took great pride in those qualities. I was obviously striving toward a kind of verbal sophistication, an urbanity, that I’m not surprised read, in our Wisconsin suburb, as queerness. I didn’t fit in, was proud not to fit in. I was a perfect target for the Pet Shop Boys’ music.

In its irreverence—indeed, its distaste—for its source material, the Pet Shop Boys’ “Always on My Mind” is working in a different register than many popular cover songs. Among the tracks in this year’s March Faxness, only a handful display even a hint of archness toward their origins. Even covers that one might expect to come from a place of disdain—the Mountain Goats’ cover of synthetic ‘90s hitmakers Ace of Base, for example—reveal themselves, upon listening, as celebrations of the originals’ tunefulness.

Or perhaps in expressing that expectation, I’m revealing my own generational cynicism. In 1987, I was just developing an aestheticism that didn’t allow for appreciation of music I viewed as simplistic, whether that took the form of Elvis’ opulence or Willie’s plainspokenness—but which did approve of a pair of British dance musicians taking a song they simply didn’t like and recasting it until they did. It seemed a thrillingly clever thing to do, snobbery in its ideal form, snobbery to aspire to—for what is snobbery, I thought then, but taste, exerted without compromise?

Just listening to the Pet Shop Boys, it was clear they had taste. They weren’t dismissive about pop music—“The Pet Shop Boys genuinely love pop music, which makes them quite rare in the music business,” Neil Tennant once told an interviewer—but about the preening and posturing that’s so much a part of the rock tradition. The journalist Chris Heath’s two remarkable books about the Pet Shop Boys—Pet Shop Boys, Literally (1990) and Pet Shop Boys versus America (1993)—include the duo’s quite astonishingly candid appraisals of nearly everyone in the contemporary pop and rock firmament. (Tennant on U2: “They’re saying nothing but they’re pretending to be something. I think they’re fake.”)

Throughout the books, which chronicle, respectively, the group’s very first tour ever (of Japan and England) and their first tour of America, Lowe and Tennant constantly enact a game which Heath calls “Let’s Play at Being Tragic Rock ‘n’ Roll Stars.” (Lowe pretends to chug a bottle of whiskey at a duty-free shop, that kind of thing.) “The point of it,” Heath writes, “is of course to emphasize how far removed they really are from all that.” Onstage, the pair abjure all rock-concert cliches, and each is ruthless with the other if he observes the slightest hint of what they view as pandering: a fist raised in the air, a mid-song “whoo!” “Don’t look triumphant,” Lowe warned Tennant just before the group’s very first TV appearance on Top of the Pops, even as “West End Girls” ascended to No. 1.

But of course despite their careful self-presentation the two love being pop stars, love making music, and love when people love their songs. This leads, in the Heath books, to delightful moments like Lowe, onstage in a stadium before thousands of fans in Hong Kong, standing completely still on stage during every song and then, the moment the lights go down, dancing furiously in place—because, he says, “it’s so exciting.”

Something in me connected in 1987 both to this skill and enthusiasm for a particular kind of artwork, the pop song, and this disdain for pompous spectacle. I was a budding fan of what was then called college rock, with little knowledge of dance music, but “Always on My Mind” struck a chord in its understated majesty. “Tell me that your sweet love hasn’t died,” Tennant sings, in his reedy tenor, his voice placid underneath a driving beat. “Give me one more chance to keep you satisfied.” The Pet Shop Boys’ song turned pleas into declarations and in doing so rendered them more relatable to me.

To many listeners, I know, Tennant’s delivery transforms the meaning of the song, changing the narrator from a man who’s overcome by sorrow to one who’s offhandedly acknowledging his own shortcomings as a partner, and who doesn’t much care. That’s an interpretation endorsed by the Pet Shop Boys themselves: Tennant has described the song’s narrator as “a selfish and self-obsessed man, who is possibly incapable of love.”

Yet teenage me didn’t hear it that way, and I still don’t. It feels too simple to read Elvis’ moaning as representing authentic sorrow and Tennant’s understated singing as representing unconcern. As a person who’s always struggled to express emotion, someone who has only recently learned not to distrust naked displays of feeling, I still find the former insincere, and the latter a true representation of a person with a limited palette going as far as he can.

Just a few years after I first heard “Always on My Mind,” my first real girlfriend broke up with me. I have a vivid memory of telling a friend of hers what had happened. We were in the high school band room just before rehearsal began, and I explained with a rueful smile that we were no longer together. “You’re smiling about it!” the friend said accusingly. “What’s wrong with you?” She read as callous the thing my body did to keep my face from crumpling, to keep me from expressing an emotion I could only view as embarrassing. I think of this moment when I read Tennant describing what he was trying to accomplish with his vocals. “I thought I sounded very sincere and my voice was dripping with emotion,” he said, “until people started congratulating me on being so deadpan”—accidentally describing not only his singing, but the experience of being a sensitive but stunted young man in the Midwest in the 1980s.

I understood, innately, that I could in liking the Pet Shop Boys’ music set myself apart from other music fans. The group, at the time, felt the same way. In Heath’s books one reason they judge other bands so harshly is because they hold themselves to such a high standard, and believe their fans—their unique, special fans—do the same. They’re constantly comparing their own achievements with those of other groups, and are constantly disgusted at what the result says about the taste of the public. “I don’t mind us not being successful,” Lowe says at one point; “it’s other people’s success I don’t like.”

But of course liking a band doesn’t actually have to mean anything. I wasn’t that unique, or that sophisticated. (For starters, the first CD I bought with my own money was Weird Al’s Even Worse, which shared with the Pet Shop Boys a kind of pleasure in taking the piss out of rock ‘n’ roll, but was hardly emblematic of the urbanity Actually represented.) It didn’t take long for my aspirational taste to harden into the kind of know-nothing snobbery that leads one to disregard whole genres of music without listening to them or even thinking seriously about them.

The Pet Shop Boys realized how ordinary their fans were on their first tour of England, years into their pop careers. It’s the tragic plot, really, of Heath’s first book. He writes:

Before this tour they had enjoyed three and a half years of imagining what Pet Shop Boys fans were like, without ever having to match their ideas up with reality. They knew one thing: whatever Pet Shop Boys fans were, they weren’t the same as other fans.…But it wasn’t like that. The London audience was…just the normal Wembley Arena crowd for a group like the Pet Shop Boys who straddle several markets. The faces may be different when Simply Red play but the overall crowd would look much the same.

“I always imagined people who like us were really quite subversive,” Lowe says, despairing. “The audience is very normal, a lot of them.”

Dan Kois, 2021, holds a drawing of Daniel Kois, 1987, made by an artist at a county fair. (My mom just gave it to me for Christmas for some reason.)

Dan Kois is a writer at Slate and the author of Facing Future (33 1/3, 2009); The World Only Spins Forward (Bloomsbury, 2018, with Isaac Butler); and How to Be a Family (Little, Brown, 2019). His first novel, Vintage Contemporaries, will be published by Harper in 2023.

“There is a sign at the sight of thee”: dev murphy on Sufjan Stevens’ “Holy, Holy, Holy”

In a dream, I can fly. I know this. I’m bursting blood vessels concentrating. I know it’s possible. It doesn’t happen.

The church felt a lot like that, growing up. I was often lonely, and I was deeply fearful. Recurrent eschatological nightmares disrupted my sleep until well into college, only stopping when I left the church in my mid-twenties. I was, and remain, afraid of the dark. In my longing for deep human connection and self-betterment as a teenager, I went to church Sundays and Wednesdays; I joined the church band (alto sax); I helped out at Vacation Bible School; I read theological and pseudo-theological literature; I did missions work in Akron, in Chicago, and in Juarez; I sought signs anywhere and everywhere, signs proving I was loved and protected by God, signs showing me the future. I burst blood vessels trying to connect with the other kids at church; I burst blood vessels trying to convince myself I would go to heaven.

—This is getting embarrassing. I don’t really want to write about the church. But this is an essay about Sufjan Stevens and a classic hymn; I don’t see a way around it.

I’m sure most artists can relate to loneliness’s double-edged sword: I doubt I would be a visual artist or writer today without the solitude I experienced growing up. My loneliness often took on the appearance of pride—at least at the time I hoped it did. Beset by my secret excruciating longing for connection but claiming “artistic integrity” (“I am a loner by choice”), I would sulk to my mother: “I hate the music they sing at church. I want to go start a church for artists.” Her response was something like, “Art isn’t why we come to church.”

As far back as I can recall, my identity was based in two things: art and God. What is a kid who wants to be an artist to do when the two are presented as mutually exclusive?

When my despair and anxiety were hard to hide, which was often, my mother—no doubt at her wit’s end—would say, “God doesn’t want you to be sad or afraid,” or, sometimes, “It’s a slap in the face of the Lord to be so unhappy.”

What is a lonely kid to do when unhappiness is presented as a choice—more than a choice, a sin?

*

“Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God Almighty” was penned by the Anglican bishop Reginald Heber in the early 1800s, though it remained unpublished until 1826, less than a year after Heber’s death. The tune, Nicaea, was penned to accompany the hymn by John Bacchus Dykes several decades later, in 1861.

The hymn is a paraphrase of Revelation 4:8-11, which depicts the ceaseless worship of God to come in heaven. Heber’s lyrics are mostly faithful to Revelation, and Sufjan Stevens’s 2006 lyrics (shortened to simply “Holy, Holy, Holy”) are mostly faithful to Heber’s hymn, the only alterations being a few lines omitted—and, notably, one line added, presumably penned by Stevens himself: There is a sign at the sight of thee / Merciful and mighty. . . . and then again, closing out the song: There is a sign at the sight of Thee / There is none beside thee. . . . The line removes us from the song’s even rhythm: it is a smooth three-four tumbling, a royal jolt, like a trumpet presenting—duh-duhduh-daaah—only humbler. Lyrically, its consonants are palindromic—Thee sigh, sigh thee, merciful and mighty…. Thee sigh, sigh thee, there is none beside thee.

Likely due to its unexpected rhythm, this is a line that flows through my head frequently, when I work, when I walk, when I wash the dishes. I have had little luck finding out anything definitive about Stevens’ songwriting choices for this cover (but I am grateful to Asthmatic Kitty Records for their encouraging response nonetheless), but members of the Sufjan Stevens Facebook fan group “Sufjan Stevens Feelsposting” suggest the line is included as a reference to the baby Jesus, to make the hymn a bit more Christmassy. I find this theory anticlimactic but sensible, since the song, while not originally penned by Heber as a Christmas carol, was covered as one by Stevens as part of a series of five Christmas EPs recorded for friends and family in the early 2000s and released as the box set Songs for Christmas in 2006.

*

If I were to map my Sufjan Stevens fandom trajectory, it might resemble the pilot’s drawing of the snake that swallowed an elephant in Le Petit Prince:

Fandom levels are imprecise, of course. And just like the elephant the snake swallowed, there are things you don’t see in this chart: God, crying, mothers, fathers, art class, working in archives, social media, church, travel, Jane Eyre, school, parties, rejection, tarot cards, astrology, grades, teaching, boyfriends, sex, moving, breakups, therapy, working in document services, dating apps, self-help columnists, working in art galleries, jogging, writing workshops, loneliness, togetherness. Considering where you could map all of those things, and where my obsession with Sufjan Stevens’ music correlates with them, which is a thing only I know, and you don’t, I will express to you that it is good that my current level of enthusiasm is only “middling.”

*

To be clear, when I say I hated the music we sang at church, I’m referring to contemporary Christian music, which is frequently, famously overblown, over-simplistic, and slightly embarrassing. I loved traditional hymns.

I know many people think that hymns are stilted, stiff, boring. Ignoring the sweepingness of that opinion, I can’t entirely disagree. I’m not even sure why I like them, but I suspect there’s something in the very stuffiness of hymns that I admired in my youth, the ascetic fastidiousness of them. The precision of both rhyme and rhythm, the imagery both magisterial and terrifying—“All the saints adore Thee, / Casting down their golden crowns around the glassy sea; / Cherubim and seraphim falling down before Thee, / Which wert, and art, and evermore shalt be.” The constancy, in juxtaposition to the underlying majesty and, occasionally, rawness of the lyrics—as distinguished from what I found to be the faux-vulnerability of much contemporary Christian music. The swells of the heart, the shivering shoulders. Slapdash. Empty. The other kids at youth group would raise their hands when the music surged and I would raise mine too (thereby instigating a mental crisis over whether it would be less authentic to raise my hands out of peer pressure, or to keep them lowered out of a desire to maintain independence).

The sturdiness, the honesty, of classic hymns like “Holy, Holy, Holy” invited my artistic study, and art goes hand in hand with exploration, something my parents and my non-denominational megachurch didn’t exactly encourage.

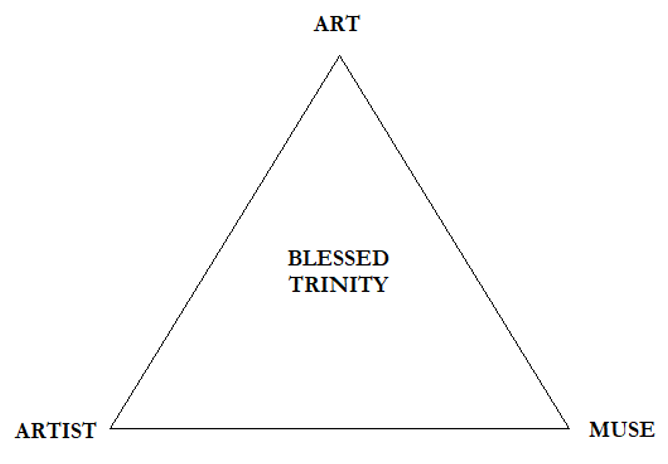

I’m maybe overcritical of contemporary Christian music, but Sufjan Stevens, and Reginald Heber, and J. B. Dykes are evidence that the moved spirit can create beautiful Christian things. To Heber, according to the poet John Betjeman, “poetic imagery was as important as didactic truth.” But with many in the church (or at least my church) insisting that any and all art created for God (and, in the sense that all humankind’s work is only possible through the will of God, by God) is by nature good, they become pro-art to the point of anti-art. In the conflation of art with artist and artist with muse and muse with art, not to mention the conflation of art with endorsement of virtue (or lack thereof), the church derides criticism against artlessness—and, in the same way, they defy celebration of artistry.

*

Like many of his celebrants, it was Sufjan Stevens’ 2005 album Illinois that hooked me when I was around fifteen or sixteen, specifically “Casimir Pulaski Day”: “Goldenrod and the 4H stone, / The things I brought you when I found out you had cancer of the bone.” The song details the narrator’s complicated experience with a friend’s cancer diagnosis, including the narrator’s attempts to heal his friend’s sickness through prayer, romantic interactions between the narrator and his friend, and the friend’s ultimate death. The last words of the song—the triumphant “All the glory when He took our place, / But He took my shoulders and He shook my face,” followed by the gently sung, “And He takes and He takes and He takes”—clenched my sad confused Christian teenage heart, not merely because of the obvious tragedy of losing a loved one the song depicted, but because this song marked the first time I could recall a so-called “Christian” artist expressing loss of faith, or expressing it in a way that isn’t cleanly resolved by the song’s (or movie’s, or book’s) end.

Sufjan Stevens was the first Christian artist who made me feel like it was possible to blend artistry and spirituality—not to mention to critique something without vitriol, and to entertain an idea without holding to it. (Stevens’ “John Wayne Gacy, Jr.” comes to mind as an extreme example.)

Sufjan Stevens’ cover of “Holy, Holy, Holy” is anything but stuffy, ascetic, or sturdy. It is ragged, humble, feels off-the-cuff. But its raggedness gives it less the appearance of a cover of a song and more of an expression of appreciation for the song—a true and honest seeing of the original song.

*

Curiously, “Holy, Holy, Holy, Lord God Almighty” was written as a rather rebellious act: from the English Civil War up until the early nineteenth century, only metrical psalms were officially allowed to be performed in the puritan Anglican Church—psalms meaning songs taken directly from scripture and therefore considered the Word of God, as opposed to hymns, which were created by humans. Heber’s hymn, being a mostly faithful paraphrase of scripture, if not an actual translation, seems to bridge the gap between “manmade” and “God-made”: it is described by The Canterbury Dictionary of Hymnology as “a fine example of Heber’s care to avoid the charge of excessive subjectivity or cheap emotionalism in his hymns, and so to win support for the use of hymns in worship within the Anglican Church.”

The slow acceptance of hymns in the Anglican church paved the way for the singing of Christmas carols within the church and, eventually, for more “popular” styles of Christian music, including, perhaps, Sufjan Stevens, and the music I hated growing up.

*

Despite my teenage appreciation for Sufjan Stevens’ ability to question religion without a clean resolution, his series of Christmas carols—many covers, many originals—represent a prodigal son-like return to Christmas.

He includes with the Songs for Christmas box set a short essay entitled “Christmas Tube Socks,” in which he delineates the unhappy Christmases spent in a tumultuous childhood home, which culminated in his eventual disenchantment with the holiday. “I decided that Christmas was a social construct, along with dating, fast food, and the Super Bowl. . . . But what I really needed was time—the slow, immeasurable convalescence that comes with getting older, wiser, more mature, and to withstand the intellectual conditioning of college and graduate school, the automation of office jobs, numerous cubicles, desk-top publishing, the morning commute, failed romantic relationships, a nervous breakdown, a death in the family, a root canal, unemployment, a recurring cold sore, weekends slouched over the classifieds, wondering how I would pay off my credit card debt. Over time, in the midst of everyday life, I completely forgot all about Christmas and how much I hated it.”

This, maybe, is what I actually admire in Sufjan Stevens’ music: not the radical rejection of faith or even simply the ability to question God, but the permission to take the space necessary for earnest seeking, the breezy acceptance of the ebbing and flowing of religious devotion, with no self-defensiveness, no sarcasm. That space, that earnest ebb and flow, yields, I think, more honest religious appreciation than I see in many other artists’ work. Rob Mitchum wrote in a Pitchfork review of Songs for Christmas, “Sufjan Stevens . . . unabashedly [revels] in the glory of Christmas with such warmth it pretty much obliterates the word ‘irony’ from the English language.”

I wonder, now, at thirty—"older, wiser, more mature,” having spent the last few years away from the pressures and the assumptions and the self-defensivenesses of the church—if maybe I will go back one day, too. Perhaps Sufjan Stevens is a sign—or this essay is.

Dev Murphy’s writing and illustrations have appeared or are forthcoming in Diagram, Shenandoah, The Cincinnati Review, The Guardian, and elsewhere. You can find her online at devmurphy.club or on social media @gytrashh. She lives in Pittsburgh with her cat, Nick.